In the polished, hyper-optimized landscape of 2026, where Low-Fi Authenticity is becoming the rarest currency, a strange phenomenon has taken over the feeds of the world’s digital natives. If you scroll through TikTok or Instagram today, you might be forgiven for thinking you’ve slipped into a time loop. The pristine, 4K, AI-stabilized video formats that dominated the early 2020s are vanishing. In their place is a visual language that is aggressively, intentionally “bad.”

We see grainy, flash-blasted photos, makeup styles that reject the “clean girl” minimalism, and a chaotic energy that feels startlingly raw. This is the 2016 Aesthetic Renaissance, and contrary to what marketing executives might think, this isn’t just another hollow fashion cycle. It is a subconscious, collective protest against the “uncanny valley” that now defines our online existence.

The Great Regression: A Protest Against Synthetic Perfection

To understand why Gen Z is romanticizing a year that many historians mark as the beginning of global political instability, we have to look beyond the chokers and the bomber jackets to the invisible villain in the room: Artificial Intelligence. As of 2026, search interest for “2016 aesthetic” has surged by 452% across major platforms, signaling a massive cultural shift.

The 2016 Renaissance is not about loving the past; it is about hating the synthetic present. In a world where AI can generate a perfect image in seconds, the only way to prove you are human is to be messy, grainy, and flawed. We are seeing a resurgence of wired headphones, Snapchat “dog filters,” and “King Kylie” aesthetics because they represent the last era of the internet that felt “human-controlled.” The grain in a photo is no longer a technical error; it is a watermark of humanity.

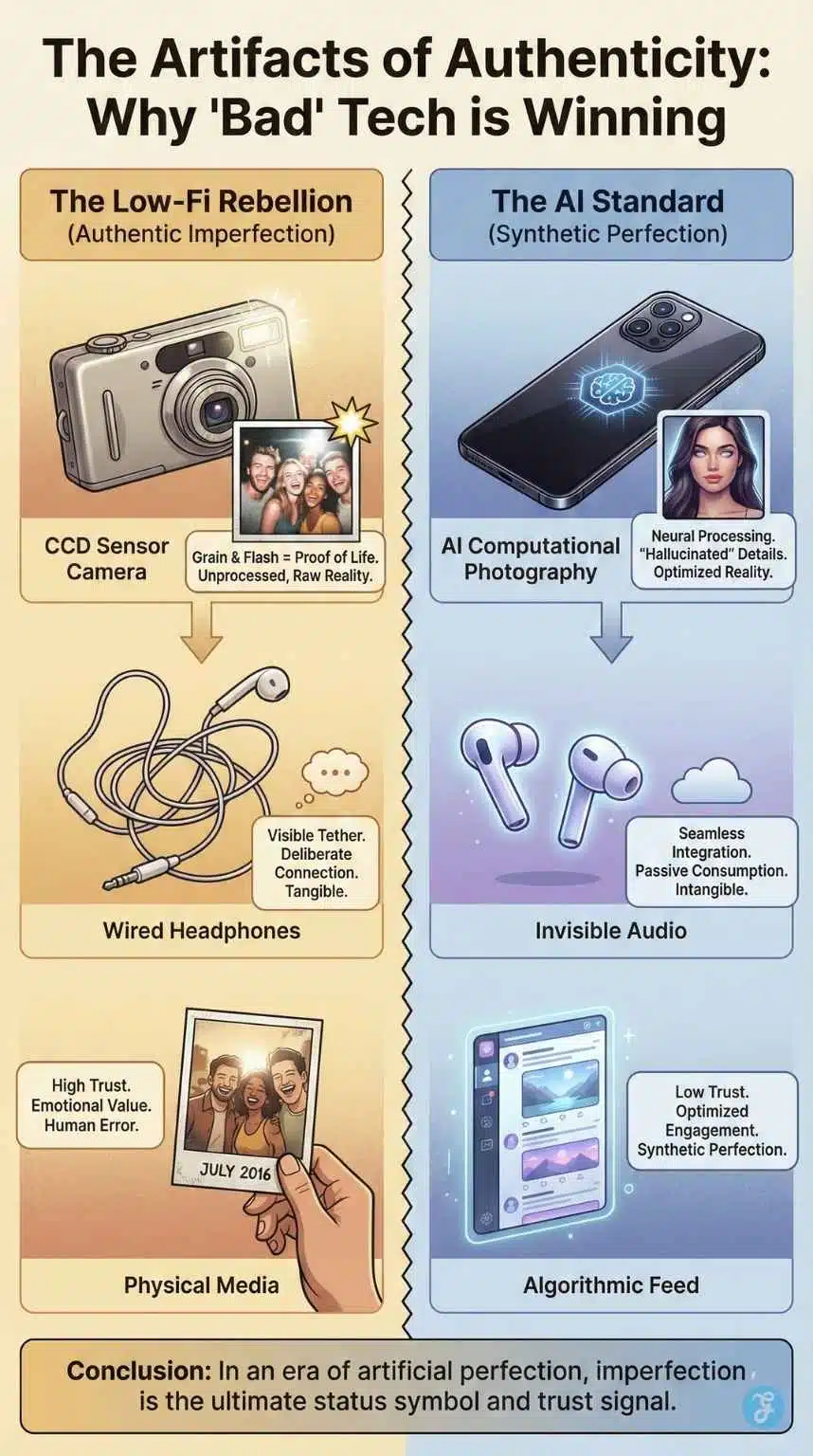

The Artifacts of Authenticity: Why “Bad” Tech is Winning

To understand the Low-Fi Authenticity movement, you first have to look at the hardware. In 2026, the smartphone camera had reached a pinnacle of technical perfection. The iPhone 17 and the latest Samsung Galaxy models use computational photography so advanced that they essentially “hallucinate” details to make a photo look better than reality. They smooth skin, balance lighting, and sharpen edges before you’ve even pressed the shutter. And Gen Z hates it.

The CCD Sensor Craze: Rejecting Computational Photography

This rejection of computational perfection has triggered a massive secondary market boom for “obsolete” digital cameras. The prices for cameras like the Canon PowerShot G7 X Mark II, the Nikon Coolpix S6900, and the Ricoh GR series have skyrocketed on eBay and Depop. Why? These cameras use older CCD sensors. They don’t have AI processing.

When you take a photo with a flash in a dark room, the background goes pitch black, the skin looks slightly blown out, and the edges are soft. In 2016, these were considered technical limitations. In 2026, they are markers of truth. A photo taken on a 2010s digicam proves that you were there. It proves that the light actually hit a sensor. It proves the image hasn’t been reconstructed by a neural network trained on billions of stolen images. The grain is a watermark of humanity. This is why the “flash-on” aesthetic has become the dominant visual style of the year. It screams, “I am not a deepfake.”

Wired Headphones: The Physical Tether

This desire for physical tethering extends to accessories. The return of wired headphones is not an audiophile choice; it is a visual choice. AirPods and invisible earbuds are seamless; they merge the human with the computer. Wired headphones are clunky. They tangle. They break. They are distinctively separate from the body.

By wearing them, Gen Z signals a separation between themselves and the machine. It is a way of saying, “I am using technology; I am not of the technology.” In an age where wearable AI aims to make technology invisible, the wire makes it visible again, reminding us of the boundaries between man and machine.

The Aesthetic of “Cringe”: Reclaiming Human Embarrassment

If the hardware is about rejecting AI processing, the aesthetic is about rejecting AI curation. The early 2020s were defined by the “Clean Girl” aesthetic, a look that was minimalist, beige, effortless, and frankly, robotic. It was a look that optimized the human face to look as close to a filtered Instagram algorithm as possible. The 2016 Aesthetic Renaissance destroys this polish.

“Instagram Face” 1.0 vs. The “Clean Girl”

We are seeing a return to “Instagram Face” 1.0, the heavy Anastasia Beverly Hills dip-brows, the overlined matte liquid lipsticks, and the intense contouring. Is it “natural”? Absolutely not. But it is humanly artificial, not digitally artificial.

It takes time and effort to apply that makeup. It is a mask of fun, a form of drag, rather than a mask of optimization. It signals intention and labor, two things AI cannot genuinely replicate. The “Clean Girl” looked like she woke up perfect; the “2016 Girl” looks like she spent two hours getting ready to have fun.

Cringe vs. Slop: The Battle for Soul

This brings us to the concept of “Cringe.” In 2016, the internet was full of “cringe.” We had the bottle flip challenge, dabbing, mustache finger tattoos, and the Mannequin Challenge. It was earnest. It was silly. It was people doing things because they were funny to their friends, not because a predictive algorithm told them it would maximize engagement time.

In 2026, we don’t have “cringe” anymore; we have “slop.” “Slop” is the term Gen Z uses for the deluge of low-effort, AI-generated content that clogs their feeds. It is the ChatGPT-written LinkedIn posts, the Midjourney-generated surrealist videos, the deepfaked influencers selling dropshipped products. “Slop” is cynical. It exists only to extract ad revenue.

The Return of the “Dog Filter”

The return to 2016 is a return to “Cringe” over “Slop.” Gen Z would rather be embarrassed by a human being trying too hard than be entertained by a machine that isn’t trying at all. The revival of the “Dog Filter” on Snapchat or the heavy “Valencia” filter on Instagram is a way of reclaiming that human embarrassment. It’s a declaration that we are allowed to be silly, messy, and unoptimized.

The Villain: Algorithmic Anxiety and the Death of Choice

To fully grasp the weight of this trend, we must acknowledge the psychological toll of the “For You” page. In 2016, Instagram was still (mostly) chronological. If you followed your best friend, you saw their brunch photo. If you followed a band, you saw their tour dates. You curated your own feed. You had autonomy.

The Death of the Chronological Feed

By 2026, the “Feed” as we know it will be dead. Social media platforms are now purely “Discovery Engines.” The algorithm decides what you see based on millions of data points, predicting your dopamine spikes with terrifying accuracy. You don’t see your friends anymore; you see content selected by an AI to keep you scrolling.

This has created a deep-seated Algorithmic Anxiety. Users feel trapped in a digital hall of mirrors where they are only shown reflections of what the machine thinks they are. The nostalgia for 2016 is a nostalgia for agency. It was the last era of the “Social Network” before it became the “Media Network.”

Marketing Reports: The Reality of AI Fatigue

Marketing reports from January 2026 confirm this shift. AI Fatigue is real and measurable. Brands that have pivoted to using AI-generated models and hyper-personalized AI ad copy are seeing conversion rates plummet among the 18-24 demographic. “It feels cheap,” one respondent noted in a recent New York Times survey. “It feels like the brand doesn’t care enough to hire a real photographer.”

The Authenticity Paradox

This is the Authenticity Paradox of 2026: The more “perfect” the marketing becomes, the less effective it is. A shaky, poorly lit TikTok video of a real person holding a product now outsells a million-dollar, AI-optimized ad campaign. The “Low-Fi” quality acts as a trust signal. It says, “There is no corporate machinery hiding behind this grain.”

The “Dead Internet” Reality Check

To understand the timing of this renaissance, we must look at the conspiracy theory that has bled into reality: The Dead Internet Theory. Internet historians and forums like Reddit have long speculated that the “human” internet effectively died around 2016-2017. Before 2016, if you argued with someone online, there was a high probability that it was a person. After 2016, the scales tipped.

In 2026, when an estimated 60% of web traffic is non-human, the “grainy photo” is no longer just an aesthetic choice; it is a CAPTCHA. Gen Z’s obsession with “Low-Fi” is a subconscious verification method. A 4K video can be generated by Sora or Runway in seconds. But a shaky, blurry photo of a half-eaten pizza with a timestamp from a digital camera? That is incredibly difficult for AI to fake convincingly because AI is trained on perfection, not mess. The “2016 Aesthetic” is essentially a human-only frequency, a way of signaling to others in the dark forest of the internet: “I am real. I am biological. I am here.”

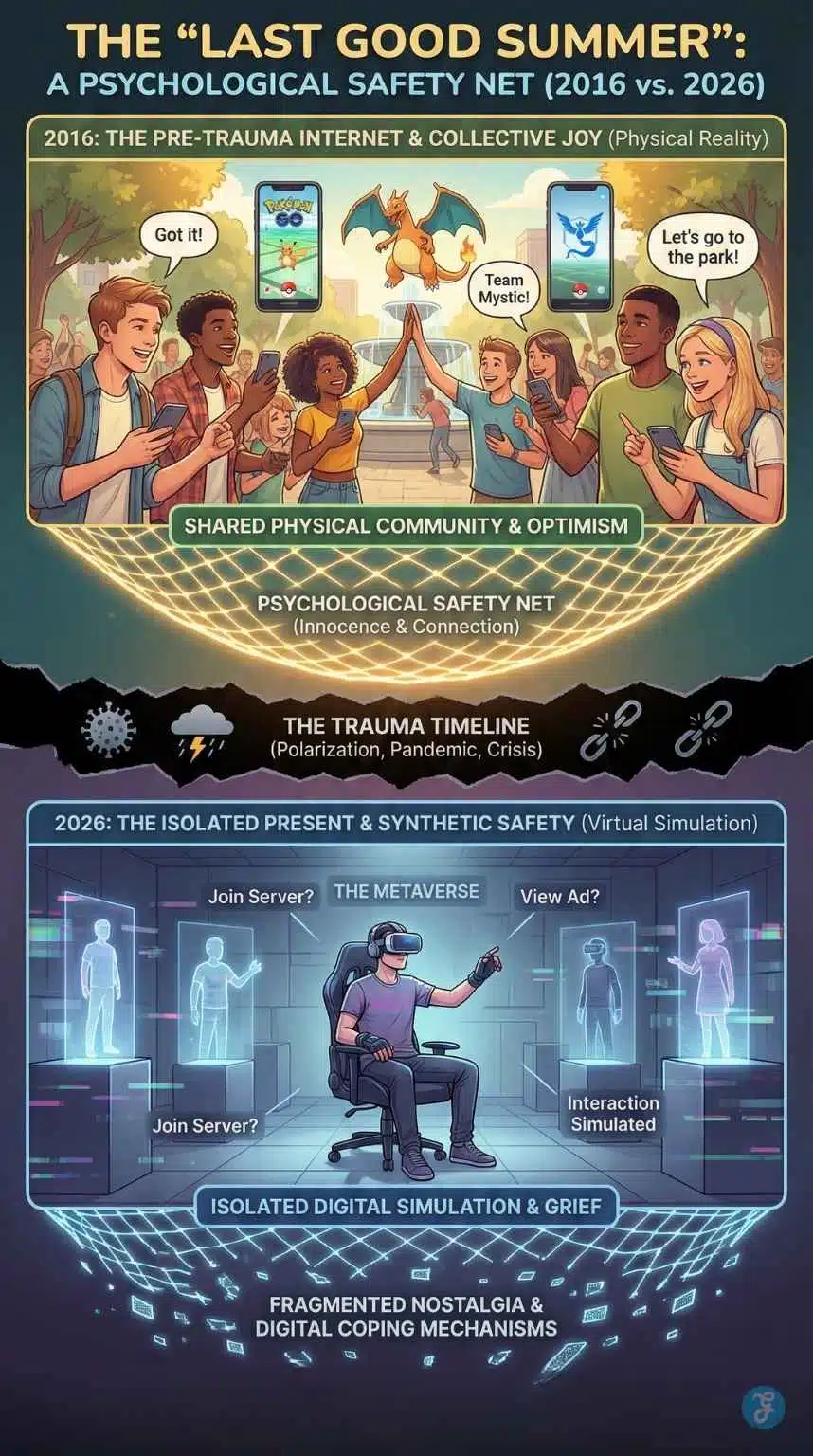

The “Last Good Summer”: A Psychological Safety Net

Beyond the tech and the aesthetics, there is a deep emotional wound driving this renaissance. 2016 is mythologized by Gen Z as the “Last Good Summer.” To the objective historian, 2016 was a turbulent year. It saw the divisive US election, the Brexit vote, and the deaths of cultural icons like David Bowie and Prince. But to a generation that was in middle school or high school at the time, it represents the final moment of innocence before the “Trauma Timeline” began.

The Pre-Trauma Internet

It was the year before the full polarization of the internet took hold. It was the year before the COVID-19 pandemic stole two years of their youth. It was the year before the climate crisis narrative shifted from “concern” to “emergency.” When a 22-year-old in 2026 posts a throwback to 2016, they aren’t just posting a photo; they are posting a memory of a time when the future still felt expansive.

Pokémon Go and the Loss of Community

The central pillar of this mythology is Pokémon Go. In the summer of 2016, for a few brief weeks, world peace felt achievable. Millions of people flooded the streets, parks, and landmarks, staring at their phones but interacting with each other. Strangers spoke to strangers. Barriers broke down. It was a moment of Augmented Reality that actually augmented reality, rather than replacing it.

Compare that to the “Metaverse” vision of 2026. The tech giants want us to strap on headsets and sit alone in our rooms, interacting with digital avatars. The contrast is heartbreaking. The 2016 nostalgia is a grief response. It is a longing for a technology that forces us outside, rather than one that keeps us inside.

Cultural Touchstones: The Soundtrack of Emotion

The cultural anchors of the 2016 Renaissance further reinforce this desire for raw emotion over synthetic perfection. The music of that year remains the soundtrack of the movement: Frank Ocean’s Blonde, Beyoncé’s Lemonade, Rihanna’s Anti, and The 1975’s I Like It When You Sleep….

“Sad Pop” and the Permission to Feel

What ties these albums together? They were messy, emotional, and deeply human projects. Frank Ocean’s Blonde, in particular, is the antithesis of AI music. It is sparse, disjointed, and aches with a specific, indescribable longing. It has “soul”, that intangible quality that generative audio models in 2026 still cannot replicate.

In 2026, music streaming services are flooded with “mood music”, AI-generated lo-fi beats, ambient noise, and generic pop tracks designed to fit perfectly into background playlists. They are functionally perfect but emotionally dead. Gen Z is returning to the 2016 charts because that music demanded to be heard. The “Sad Pop” era allowed teenagers to feel angst, sadness, and confusion. In the toxic positivity of the algorithmic feed, the permission to be sad feels revolutionary.

Collective Humor in a Siloed World

Even the humor of 2016, the “Harambe” memes, “Damn Daniel,” the absurdist Vine energy, feels refreshingly collective. In 2026, algorithms have siloed us into such specific niches that we no longer share a common language. I might see a meme that is hilarious to me but incomprehensible to my neighbor. In 2016, the jokes were global. We laughed at the same things. We felt like a single internet.

“Friction-Maxxing”: The New Status Symbol

This movement has birthed a new behavioral trend in 2026: “Friction-Maxxing.” For the last decade, Silicon Valley’s goal was “frictionless” living. One-click checkout. Instant streaming. Predictive text. But the 2016 Renaissance treats inconvenience as a luxury good.

We see this in the exploding resale market for “dumb phones” (feature phones). Pulling out a flip phone at a party is the 2026 equivalent of pulling out a platinum credit card. It signals that you are powerful enough to be unreachable. It signals that your attention is not for sale.

Transferring photos from a Canon PowerShot to a laptop via a cable is annoying. It takes time. It is friction. And that is exactly the point. In a world of instant gratification, the act of waiting for something gives it value. The “process” is the antidote to the “prompt.” By choosing the harder, slower way to document their lives, Gen Z is reclaiming the sensation of living time, rather than just scrolling through it.

The Privilege of Selective Memory

However, we must be careful not to flatten history. The irony of the “2016 Renaissance” is that for many, 2016 was not a “good” year; it was the beginning of the crisis. It was the year of a polarizing US election, the Brexit referendum, the Pulse nightclub shooting, and the start of the “post-truth” era.

The version of 2016 being celebrated on TikTok is a sanitized, curated hallucination. It focuses on the vibes (the music, the makeup) while deleting the volatility. This trend essentially cherry-picks the optimism of the pre-pandemic world while ignoring the instability that created it.

Furthermore, there is an inherent privilege in “Low-Fi Cosplay.” Choosing to use a dumb phone or a grainy camera is an aesthetic choice only available to those who don’t need a smartphone for the gig economy or who don’t need high-definition visuals for professional credibility. For the digital working class, high-tech optimization is a survival requirement. For the “2016 Renaissance” kids, low-tech inefficiency is a leisure activity. It is “poverty cosplay” for a generation that is technically drowning but aesthetically thriving.

The Future of Imperfection

So, where does the 2016 Renaissance go from here? Is it just a fad that will burn out by 2027? Unlikely. The 2016 trend is not a fashion statement; it is a correction. It is the pendulum swinging back from the extreme digitalization of human life. As AI becomes more integrated into our jobs, our homes, and our creative processes, the value of the “un-AI” will only increase.

The Economy of Proven Human Effort

We are entering an economy of Proven Human Effort. In the future, “Low-Fi” won’t just be an aesthetic; it will be a luxury good. Handwritten notes, film photography, live unautotuned music, and “bad” video quality will be the ultimate signals of wealth and status. They will signify that you can afford to be inefficient in an efficient world.

A Call to Creators: Embrace the Grain

For creators and brands, the lesson is clear: Stop trying to out-robot the robot. You cannot beat the AI at perfection. It will always be faster, smoother, and cleaner than you. Instead, double down on your flaws. Embrace the grain. Leave the background noise in the video. Post the photo where your eyes are half-closed, but your smile is real.

In a sea of synthetic “slop,” the most disruptive thing you can be is human. The 2016 Renaissance isn’t about going back in time. It’s about retrieving the things we left behind, autonomy, community, imperfection, and dragging them with us into the future. It’s a reminder that no matter how smart the machine gets, it will never know what it feels like to catch a Charizard in a park on a warm July evening, surrounded by strangers who feel like friends.

Final Thought: The Rebellion of the Real

Ultimately, this renaissance is not about nostalgia for a specific year; it is a rebellion against a specific future. We were promised that AI would make our lives “better” by smoothing out the edges, removing the noise, and optimizing our creativity. But it turns out that the edges, the noise, and the struggle were the point all along.

We are witnessing the birth of a new class divide: those who are content to consume the synthetic “slop” of the machine, and those who have the luxury, the time, and the will to seek out the Low-Fi. In an age of artificial perfection, “human error” is no longer a mistake to be fixed; it is the ultimate proof of life. The revolution will not be televised in 4K; it will be captured on a grainy, ten-year-old digital camera, and it will be beautiful because it is flawed.