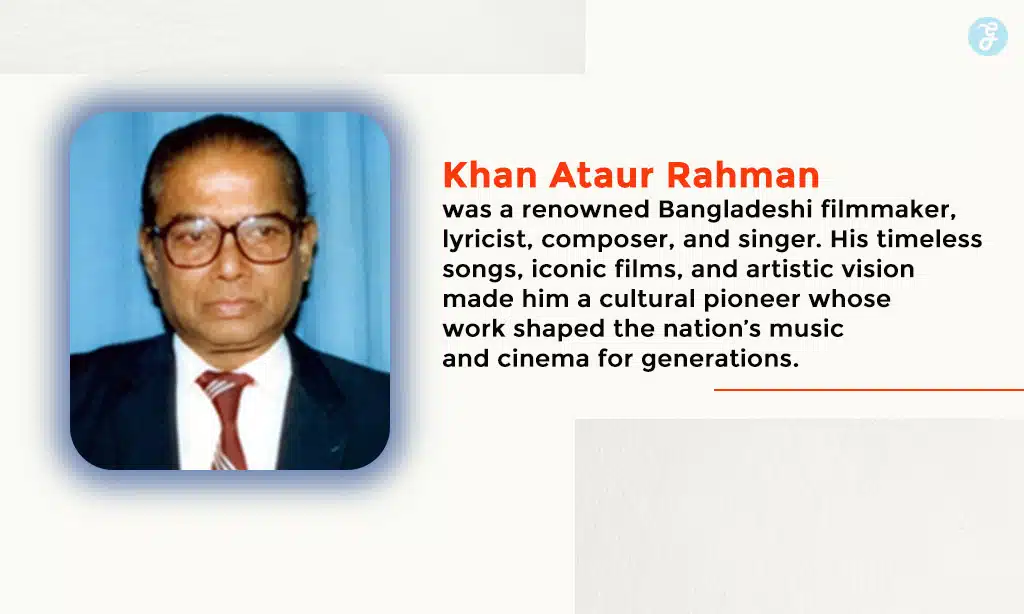

Khan Ataur Rahman was not just a familiar face on the silver screen. He was a complete creative force who acted, directed, wrote scripts, composed music, and sang. For many viewers, he represents an entire era of Bangladeshi cinema, where film, music, and politics were deeply intertwined. When people talk about classic Bengali films, his name comes up again and again. In any serious discussion of cultural history, Khan Ataur Rahman is impossible to ignore.

Born in what is now Manikganj district, he grew from a gifted village boy into one of the most influential film personalities of Bangladesh. He worked in front of the camera and behind it, and his films still feel relevant because they deal with power, injustice, love, and ordinary life.

Khan Ataur Rahman was one of the rare artists who could carry a story with his acting, give it structure with his screenplay, and then deepen it with his own music and lyrics. That range made him unique even in a rich film culture. Today, audiences and critics look back at his work not only for nostalgia, but also to understand how cinema can reflect and shape a nation.

This article explores the many shades of Khan Ataur Rahman, from his early life to his work as an actor, director, and musician, and finally his lasting legacy and influence on modern cinema.

Khan Ataur Rahman at a Glance

Before going deeper into his life, it helps to have a quick overview of who he was and what he did.

Khan Ataur Rahman was born on 11 December 1928 in Ramkantapur village of Singair, Manikganj, in what was then the Bengal Presidency under British India. He later became known simply as Khan Ata. He studied at Dhaka Collegiate School, Dhaka College, and the University of Dhaka, where he completed a Bachelor of Science after briefly enrolling at Dhaka Medical College.

Here is a snapshot of his life and work.

| Aspect | Detail |

| Full name | Khan Ataur Rahman |

| Popular name | Khan Ata |

| Born | 11 December 1928, Ramkantapur, Singair, Manikganj |

| Died | 1 December 1997, Dhaka |

| Main roles | Actor, film director, producer, screenwriter, music composer, singer |

| Notable films | Jibon Theke Neya, Nawab Sirajuddaula, Sujon Sokhi, Danpite Chhele |

| Major national awards | Bangladesh National Film Awards, Ekushey Padak |

| Active years | 1960s to late 1990s |

This quick view already shows why he occupies such an important place in cultural history. He did not belong to one single role. He moved between many, often in the same project.

Early Life, Education, and Artistic Roots

Khan Ataur Rahman grew up in a rural setting, but his life quickly became linked with Dhaka and its educational and cultural institutions. As a schoolboy, he won first prize in the Dhaka Zilla Music Competition when he was in class three, which hints at how early his talent appeared.

He went on to study at Dhaka Collegiate School, where many future intellectuals and artists also studied. Then he joined Dhaka College for his higher secondary education, followed by Dhaka Medical College. Medical studies, however, did not hold his interest. He left medicine and completed a Bachelor of Science at the University of Dhaka instead.

From a young age, he had what contemporaries described as a somewhat bohemian personality. He was drawn to music and performance more than to conventional career paths. During his student days, he met other important cultural figures and began taking music lessons from established masters. These early connections and experiences created the foundation for his later creative life.

The combination of formal education and artistic exploration gave him a broad outlook. He understood both rural and urban life, and his later films often show this mix of perspectives.

Rising Through Radio, Stage, and Early Film

Before becoming a major film director, Khan Ataur Rahman built his reputation through music, radio, and acting. In those days, radio was a powerful medium in East Pakistan, and performing there gave artists national exposure.

He worked as a singer and musician, which helped him develop a strong sense of how music supports storytelling. That knowledge became important later, when he started composing and directing film songs.

His first major screen presence came with the Urdu film Jago Hua Savera, one of the earliest full-length features made in Dhaka. In that movie, he appeared as the hero, marking the beginning of his on-screen career.

This period also sharpened his sense of how film industries function. He saw the financial pressures, the creative compromises, and the political context of filmmaking in a region that was still part of Pakistan. These experiences helped shape the kind of films he would later make, often with a strong political or social message.

Actor on Screen: The Face of a Changing Bengal

Khan Ataur Rahman is widely remembered as an actor who brought depth and realism to his characters. His most famous role is in the film Jibon Theke Neya, released in 1970, where he played one of the key male protagonists in a story that used a family drama to comment on dictatorship and resistance.

On screen, he often played ordinary men dealing with oppressive systems, family conflict, or moral dilemmas. He did not rely on exaggerated gestures or stylized acting. Instead, he used natural dialogue and restrained body language, which made his characters feel close to real life.

His acting also benefited from his training as a musician and writer. He understood rhythm, timing, and emotional pacing. This allowed him to shift between humor, pathos, and anger within a single scene without breaking the overall tone of the story.

For many viewers, his face became associated with a period when Bangladeshi cinema was pushing against censorship and trying to express the political concerns of the time. The period leading up to the Liberation War and its aftermath is strongly reflected in his body of work.

Director and Storyteller: Cinema as Social Mirror

If his acting drew attention, his directing and storytelling made his name permanent. As a director and screenwriter, Khan Ataur Rahman showed how film could be both popular entertainment and sharp social commentary.

Two of his most important works are Nawab Sirajuddaula, released in 1967, and Jibon Theke Neya, released in 1970. Nawab Sirajuddaula retold the story of the last independent Nawab of Bengal, linking colonial betrayal and resistance with modern political feelings. Jibon Theke Neya used the metaphor of a family run by a cruel, authoritarian woman to criticize undemocratic rule in Pakistan.

Later, as Bangladesh became independent, he continued to explore social tensions in films like Sujon Sokhi and Danpite Chhele. For these two movies, he won the Bangladesh National Film Award for Best Screenplay, which shows how highly the industry valued his writing.

Here is a simplified overview of a few key films he shaped as a director or writer.

| Film | Year | Role | Key Theme |

| Nawab Sirajuddaula | 1967 | Director | Anti-colonial history, betrayal |

| Jibon Theke Neya | 1970 | Actor, creative collaborator | Authoritarianism, resistance |

| Sujon Sokhi | 1975 | Screenwriter | Rural love, class, sacrifice |

| Danpite Chhele | 1980 | Screenwriter | Family, morality, social values |

Through these works, he used cinema as a mirror for society. His stories often gave voice to ordinary people standing up against injustice, which matched the public mood of the time.

Khan Ataur Rahman and the Rise of Political Cinema in Bangladesh

To understand his place in history, it is important to see Khan Ataur Rahman as a key figure in the growth of political cinema in what became Bangladesh. He worked at a time when film was more than entertainment. It was one of the few mass media tools available to challenge narratives coming from the state.

In Jibon Theke Neya, the controlling elder sister, surrounded by caged birds and ruling the household through fear and manipulation, was widely read as a symbol of authoritarian rule. Audiences recognized the connection without needing it spelled out. The film became an artistic echo of the growing movement for self-determination and democracy.

His historical film Nawab Sirajuddaula also had a political edge. By returning to the story of a betrayed ruler who resisted foreign control, it reminded viewers of the long history of struggle in Bengal and the cost of internal division.

Pro Tip: If you want to understand the politics of the late 1960s and early 1970s in this region, watch these films alongside timelines of real events. The parallels between the fictional stories and the political news of those years are often striking.

After independence, political themes did not disappear from his work. They became more subtle, often wrapped in family plots and rural dramas. Land, class, injustice, and power remained at the core of many of his stories. In this way, Khan Ataur Rahman helped build a tradition of cinema that could speak to public life without always being directly didactic.

Musician, Lyricist, and Composer: A Complete Music Mind

Khan Ataur Rahman was also a full-fledged music mind. He composed, wrote lyrics, and sang. In many projects, he was responsible for both the narrative and the sound of a film, which allowed him to match songs and scenes very closely.

He worked as a music director and composer for various films over several decades, including projects in both Bengali and Urdu. His style blended classical and folk elements, often with simple, memorable melodies that carried strong emotional weight.

Late in his career, he received the Bangladesh National Film Award for Best Music Director and Best Lyricist for the film Ekhono Onek Raat, released in 1997. This recognition came near the end of his life, which shows that his musical contributions remained relevant up to his final years.

For many fans, songs linked to his films still circulate on radio, television, and digital platforms. While new generations may not always know which tracks he wrote or composed, they often know the melodies. In this quiet way, Khan Ataur Rahman continues to shape musical taste and memory.

Artistic Vision: How Khan Ataur Rahman Approached Storytelling

One of the most interesting questions about any artist is how they think about their craft. In the case of Khan Ataur Rahman, his body of work reveals a clear set of preferences and patterns.

First, he liked stories that connected the personal and the political. Families in his films are never isolated from the wider world. Power struggles at home reflect power struggles in society. A controlling parent, a greedy landlord, or an unfair employer often stands in for larger structures of injustice.

Second, he used metaphors and symbols in ways that were easy to understand but still powerful. The caged birds in Jibon Theke Neya, the court and battlefield in Nawab Sirajuddaula, and the rural fields in Sujon Sokhi all carry a second meaning beyond their surface appearance.

Third, he cared about natural dialogue. Even when the themes were heavy, characters spoke in a way that ordinary people could relate to. This was true both in urban settings and village scenes. His own experience moving between rural Manikganj and urban Dhaka helped him write speech patterns that felt authentic.

Fourth, he took music seriously as part of storytelling, not as a separate decorative layer. Songs in his films often reveal inner emotions, mark turning points, or comment on the action. Because he was both a writer and a composer, he could design these scenes very precisely.

Pro Tip: When you watch his films, pay attention to when the songs appear. Ask yourself what has changed in the story before and after a song. Often, the music marks a shift that might be easy to miss if you focus only on dialogue.

Working Across Borders: Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Beyond

Another shade of Khan Ataur Rahman is his cross-border role. Before 1971, he worked in what was then East Pakistan, and he also contributed to Urdu films that reached wider audiences across Pakistan. For example, he acted in the pioneering Urdu film Jago Hua Savera and composed music for several other movies.

This cross-regional experience gave him a broader understanding of South Asian film traditions. After Bangladesh became independent, he became one of the key figures who helped define what Bangladeshi cinema would look and sound like, distinct from Pakistani and Indian industries.

Working in both Bengali and Urdu, and sometimes with international collaborators, he proved that strong local stories could travel beyond their immediate setting. This is still a useful lesson for modern filmmakers who want to make locally grounded, globally relevant work.

Awards, Honors, and Institutional Recognition

Khan Ataur Rahman received several major national honors, which confirm his importance in Bangladeshi cultural life.

He was awarded the Bangladesh National Film Award for Best Screenplay for Sujon Sokhi in 1975 and Danpite Chhele in 1980. Later, he also received the National Film Award for music-related categories for Ekhono Onek Raat.

In 2003, some years after his death in 1997, the Government of Bangladesh awarded him the Ekushey Padak for his contribution to film and culture, one of the country’s highest civilian honors.

A simple timeline helps to place these recognitions.

| Year | Award | Category | Work |

| 1975 | Bangladesh National Film Award | Best Screenplay | Sujon Sokhi |

| 1980 | Bangladesh National Film Award | Best Screenplay | Danpite Chhele |

| 1997 | Bangladesh National Film Award | Music direction and lyrics | Ekhono Onek Raat |

| 2003 | Ekushey Padak | Film and culture | Lifetime contribution |

These awards show that different sides of his talent were honored over time. He was recognized as a writer, a music director, and a lyricist, on top of his fame as an actor and director.

Personal Life and Family Connections

Khan Ataur Rahman’s personal life was also closely connected to the arts. He was born to Ziarat Hossain Khan and Zohra Khatun. Over time, he married three times, including to well-known singers Mahbuba Rahman and later Nilufar Yasmin, both respected voices in Bangladeshi music.

His children also entered the cultural field. His son, Khan Asifur Rahman Agun, became a popular singer and musician, and his daughter, Rumana Islam, is also known as a singer. This continuity shows how his home environment was filled with music and performance and how that atmosphere carried into the next generation.

Although he was deeply involved in film and music, he also experienced the usual pressures of work, family, and health. He passed away on 1 December 1997 in Dhaka at the age of 68. Even after his death, his family and collaborators have helped keep his memory alive through concerts, film screenings, and media features.

Influence on Today’s Cinema and Cultural Identity

More than two decades after his death, the influence of Khan Ataur Rahman can still be felt in present-day Bangladeshi cinema and television.

Directors who focus on social issues, political allegory, or rural life often follow trails he helped open. The idea that a film can be mainstream and still carry a critique of power owes a lot to films like Jibon Theke Neya.

Many modern filmmakers borrow his approach of combining realism with clear symbolism. They may not copy his style directly, but they share his belief that stories about families, villages, and ordinary people can carry national-level questions.

In music, the blending of folk and modern elements in film songs has also become standard practice. Khan Ataur Rahman was one of the early architects of this blend, which now feels natural to audiences.

Pro Tip: If you are a young filmmaker or writer, study how his films handle pacing. Notice how he balances slow, reflective scenes with moments of strong emotional release. This kind of rhythm is still useful for modern storytelling, whether for cinema, web series, or streaming platforms.

Preserving Khan Ataur Rahman’s Legacy: Archives, Restoration, and Memory

Like many film industries in South Asia, Bangladesh has struggled with preserving its older films. Physical reels can be damaged by humidity, mishandling, or simple neglect. As a result, not all of Khan Ataur Rahman’s works are available in clean, restored versions.

Some of his most important films have been digitized or re-released on television and online platforms. However, copies are sometimes of low quality, and full restoration is expensive. This makes it harder for younger audiences to experience the visual and sound design as it was intended.

There are ongoing efforts, both official and unofficial, to protect classic films. These include:

- Archiving and digitizing reels held by government institutions.

- Private collectors sharing rare prints for preservation.

- Television channels and online platforms are re-running classic films and concert footage.

For a figure like Khan Ataur Rahman, preservation is not just about saving old movies. It is about keeping alive a key chapter of the country’s cultural and political history.

If more of his films are restored and made widely accessible, future filmmakers, students, and general viewers will be able to engage with his work on a deeper level. That would help ensure that his influence does not fade as technology and viewing habits change.

How to Experience Khan Ataur Rahman Today

For a new viewer or listener, the body of work attached to Khan Ataur Rahman can feel large and a little overwhelming. A simple way to explore his legacy is to start with a mix of films and songs.

Good starting points include:

- Jibon Theke Neya, to see his performance and the political strength of his era.

- Nawab Sirajuddaula, to understand his approach to historical drama.

- Sujon Sokhi and Danpite Chhele, to feel his storytelling in more domestic, emotional settings.

- Selected songs from Ekhono Onek Raat and other soundtracks he composed or wrote.

If you are interested in filmmaking, you can also study how Khan Ataur Rahman uses songs in stories. The way he places musical numbers often reveals the inner feelings of characters or shifts the emotional tone of the narrative. This is one reason his work remains a useful reference for students of cinema and music.

Final Thoughts on Khan Ataur Rahman

Khan Ataur Rahman was many things at once, and that is what makes him so compelling. He was an actor, a director, a screenwriter, a music composer, a singer, and a cultural thinker. Through these different roles, he helped shape the language of Bangladeshi cinema and music at a crucial time in the country’s history.

He showed that films could be entertaining and politically sharp at the same time, that songs could be both popular and meaningful, and that an artist could move between different crafts without losing focus. For anyone studying South Asian film or music, Khan Ataur Rahman remains a central figure.

In the end, his story is not only about one talented man. It is also about how creative work can capture the hopes, fears, and struggles of a people. Remembering Khan Ataur Rahman means remembering a period when art and life, politics and poetry, were tightly bound together. His work invites us to keep asking how cinema and music can still speak to issues of power, justice, and everyday human experience.

FAQs About Khan Ataur Rahman

When and where was Khan Ataur Rahman born?

He was born on 11 December 1928 in Ramkantapur village of Singair in Manikganj district, in what was then the Bengal Presidency under British India.

What is Khan Ataur Rahman best known for?

He is best known as a Bangladeshi film actor, director, producer, screenwriter, music composer, and singer, especially for his involvement in the film Jibon Theke Neya and for directing Nawab Sirajuddaula and other influential works.

Which awards did he receive during his career?

He received Bangladesh National Film Awards for Best Screenplay for Sujon Sokhi and Danpite Chhele and later awards for his music work in Ekhono Onek Raat. He was also honored with the Ekushey Padak for his contribution to film and culture.

What are some of his most important films?

Key films connected to him include Nawab Sirajuddaula, Jibon Theke Neya, Sujon Sokhi, Danpite Chhele, and Ekhono Onek Raat. These movies together show his strength as an actor, director, writer, and music director.

How did Khan Ataur Rahman influence Bangladeshi cinema?

He helped define the style and themes of early Bangladeshi cinema. By mixing political messages with strong stories and memorable music, he showed that local films could address national issues and still connect with ordinary audiences.