You may wonder why equal education and women’s rights took so long in India. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, a bold social reformer, changed that story in the Bengal Renaissance. His work opened Sanskrit College to more students, cut fees, and pushed for the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856. He also wrote clear, simple books that shaped modern Bengali prose and the Bengali alphabet.

If you’ve faced unfair rules at school or seen girls get fewer choices, this history matters. Vidyasagar’s actions show how one person’s steady effort can move a whole system. You’ll see how he used books, laws, and training to make change that still helps people today.

Key Takeaways

- In 1851, Vidyasagar opened Sanskrit College to non-Brahmin students and lowered fees so poor children could study.

- He led the push for the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act of 1856 and gathered over 25,000 signatures against polygamy.

- He added English and Bengali lessons alongside Sanskrit, wrote simpler textbooks like “Borno Porichoy,” and made books affordable.

- His writings such as “Bidhobabivah” and campaigns against child marriage changed social laws during the Bengal Renaissance.

- Thinkers like Rabindranath Tagore praised him as the father of Bengali prose, showing his power over language and reform.

Early Life and Education of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar grew up in Birsingha village in the Midnapore district. He walked long distances to study at Sanskrit College in Calcutta. His family had little money, but his hunger for learning never faded.

Financial constraints and academic excellence

Vidyasagar was born into deep poverty. His father struggled to pay even a small admission fee or buy books. Many nights, he studied under street lamps because he had no candles at home.

Hard work paid off. He won scholarships again and again due to strong results. To help his family and fund school needs, he taught part-time while still a student. These struggles shaped his values. He chose to fight for students who faced barriers, especially non-Brahmin youth shut out by old rules across Bengal and West Bengal.

Contributions to Education

Vidyasagar believed schools should open minds, not guard gates. He used policy, curriculum, and teacher training to make that real.

Reformation of scholastic system

At Sanskrit College, he challenged the narrow focus on only Vedic study and Sanskrit grammar. He brought in science, European history, and philosophy, giving students a wider view of the world. That shift prepared learners to think, compare, and question.

He also removed caste barriers. Non-Brahmin students could enroll and study core texts. This was a bold move in the 1850s and it spread to other schools in Calcutta and the Midnapore district. One student, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, later became a famous Bengali poet. Change in one college sparked change in many classrooms.

Introduction of English and Bengali alongside Sanskrit

Classrooms had centered only on Sanskrit. As principal in 1851, Vidyasagar added English and Bengali as regular subjects. That choice included more students, especially those who had been excluded by language and caste.

He wrote textbooks like “Upakramonika” and “Byakaran Koumudi,” turning tough Sanskrit grammar into clear Bengali. He simplified the Bengali alphabet to 12 vowels and 40 consonants so children could learn faster. This helped students from Birsingha village and the broader Midnapore district enter modern learning without fear.

Modification of admission policies at Sanskrit College

In 1851, as Principal of Sanskrit College, Calcutta, he changed admissions. Non-Brahmin students could join. Fees were cut so poor but bright students were not turned away. That one policy opened doors for farmers’ and weavers’ children who had long been barred.

The move upset some leaders like Radhakanta Deb and the Dharma Sabha. British authorities watched carefully, yet the reforms stood. Students now studied Sanskrit grammar alongside English and Bengali. Thinkers such as Michael Madhusudan Dutta grew in that climate of wider access.

Establishment of the Normal School for teacher training

Great schools need great teachers. To build that base, Vidyasagar started a Normal School in Calcutta to train teachers in clear methods. In 1855, while leading Sanskrit College, he pushed for professional preparation in English, Bengali, and Sanskrit instruction.

Many trainees came from towns and villages across the region. Trained teachers then spread better lessons to local schools. Linked with work at Fort William College, this approach lifted classroom quality across Bengal. It gave children steady guides on their path through what people call vidyasagar, an ocean of knowledge.

Contributions to Society

Vidyasagar did not stop at school reform. He took on unfair customs that harmed women and children.

Advocacy for women’s empowerment

He stood firm for women’s rights. He challenged child marriage and worked so widows could remarry with dignity. Using careful study of the Vedas and other texts, he showed that the faith did not demand cruelty. His effort helped pass the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856.

He also backed girls’ schools across the Midnapore district and beyond. Through simple books like “Borno Porichoy,” he made reading easier for young learners. Many called him the father of Bengali prose because he wrote in clear, direct Bengali that spoke to everyone.

Campaign against child marriage and promotion of widow remarriage

Child marriage trapped young girls and created a harsh life for adolescent widows. Vidyasagar wrote powerful books that exposed this pain and argued for change. People listened, even some who had once opposed him.

On October 14, 1855, he sent a petition to the British authorities asking for a legal path to widow remarriage. After months of debate in Calcutta, the law passed on July 16, 1856. Soon, reformers in other regions supported new widow marriages as well. By 1866, he had also gathered more than 21,000 signatures against polygamy. These steps pushed society forward during the Bengal Renaissance.

Literary works addressing social and moral issues

He fought with facts and with stories. “Bidhobabivah” in 1855 defended widow remarriage and sold thousands of copies in one week. In 1871, “Bahubivah” argued against polygamy and urged lawmakers to stop the practice.

“Balyabivah” took on child marriage, showing the harm done to young girls. He wrote in plain Bengali, not dense Sanskrit or elite English, so villagers could understand him. Debates grew loud at Dharma Sabha and Sanskrit College, yet many thinkers agreed with him, including Rabindranath Tagore and Michael Madhusudan Dutta. Officials in power had to take notice.

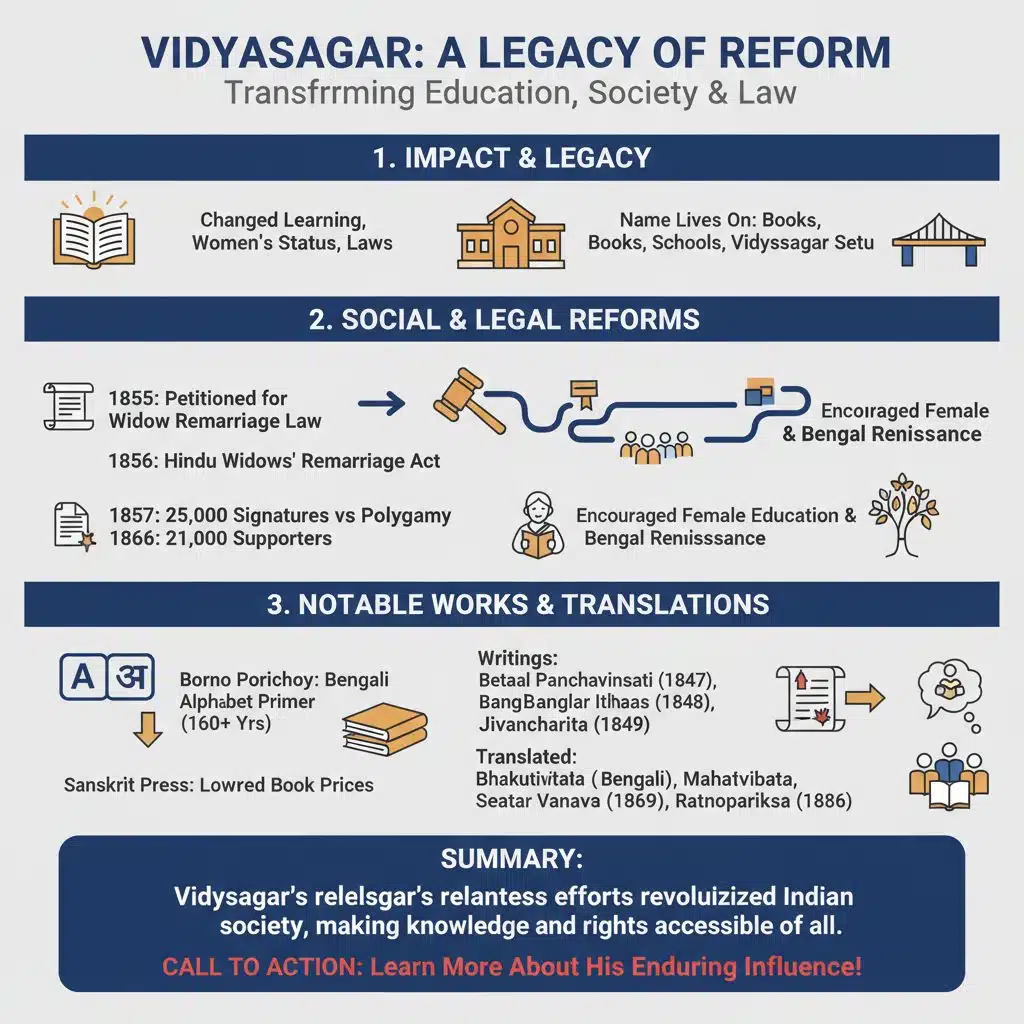

Impact and Legacy

Vidyasagar’s ideas changed how people learned, how society judged women, and how laws were written. His name lives on in books, schools, and even bridges like Vidyasagar Setu near Howrah.

Influence on Hindu society and legal reforms

In 1855, he petitioned for a law to allow widow remarriage. The result was the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856. That law gave hope to many who had been forced into a life of silence and shame.

He kept pushing. In 1857, he collected 25,000 signatures to fight polygamy among Kulin Brahmins, and again drew 21,000 supporters in 1866. His voice made leaders rethink what was fair under Hinduism. Those efforts also encouraged female education and set a new course during the Bengal Renaissance.

Notable works and translations

“Borno Porichoy,” his primer on the Bengali alphabet, has taught children to read for more than 160 years. Through the Sanskrit Press, he lowered book prices so anyone could learn.

His range was wide. He wrote “Betaal Panchavinsati” in 1847, “Banglar Itihaas” in 1848, and “Jivancharita” in 1849. He translated Kalidasa’s “Shakuntala” into simple Bengali so everyday readers could enjoy a classic. He also worked on the Mahabharata in 1860 and stories like “Seetar Vanavas.” Social lessons shine in “Bhrantivilaas” from 1869 and “Ratnopariksha” from 1886. These choices made reading more open to all classes.

Takeaways

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar used courage and care to change Bengal. As Principal of Sanskrit College, he opened admissions to non-Brahmin students and cut tuition so talent could rise. His push led to the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856, and his simple prose shaped how Bengali is written and taught.

Classrooms under his watch taught Sanskrit with English and Bengali, which widened horizons for girls and boys. Rabindranath Tagore called him the father of Bengali prose, and you can see why. “Borno Porichoy” still teaches first letters to children today.

Walk through Birsingha village or pass a free homeopathy clinic linked to his name, and you feel his spirit. The lessons are clear. Fair rules, open schools, and good books can change lives for a long time.

FAQs on Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar

1. Who was Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and why is he called the “ocean of knowledge”?

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, born in Birsingha village in Midnapore district, earned the title “Vidyasagar,” meaning ocean of knowledge, for his deep learning. He mastered Sanskrit grammar at Sanskrit College, Calcutta, and later became its principal. His work with Fort William College also shaped him as a top Indian educator.

2. What role did Vidyasagar play during the Bengal Renaissance?

He stood tall as a social reformer during the Bengal Renaissance. He fought against child marriage and pushed for widow remarriage rights through the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act of 1856. His actions made waves across Bengal society.

3. How did Vidyasagar support female education?

Vidyasagar believed every girl deserved to learn just like boys did. He opened schools for girls and even set up free homeopathy clinics near Nandan Kanan to help families trust new ideas about health and schooling.

4. Why do people call him the father of Bengali prose?

He wrote Borno Porichoy to teach kids the Bengali alphabet simply and clearly; this book still helps children today! Rabindranath Tagore praised his clear style too; it changed how people read Bengali books forever.

5. Did Vidyasagar help students from all backgrounds study at Sanskrit College?

Yes, he welcomed non-Brahmin students by lowering admission fees and tuition fees so more could attend classes at Sanskrit College, Calcutta; that was rare back then! Teacher training improved under his watchful eye as well.

6. Which famous figures were influenced by Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s work?

Michael Madhusudan Dutta admired him deeply; Swami Vivekananda respected his courage too; John Peter Grant worked with him on laws like widow remarriage; even poets such as Rabindranath Tagore saw him as a guiding light during those years when change swept through India’s heartlands.