Have you ever read a story where the characters felt so real it was almost uncomfortable? You know, the kind where heroes aren’t perfect, and good people have dark, messy thoughts? If you are tired of flat characters and predictable endings, you need to meet Manik Bandopadhyay.

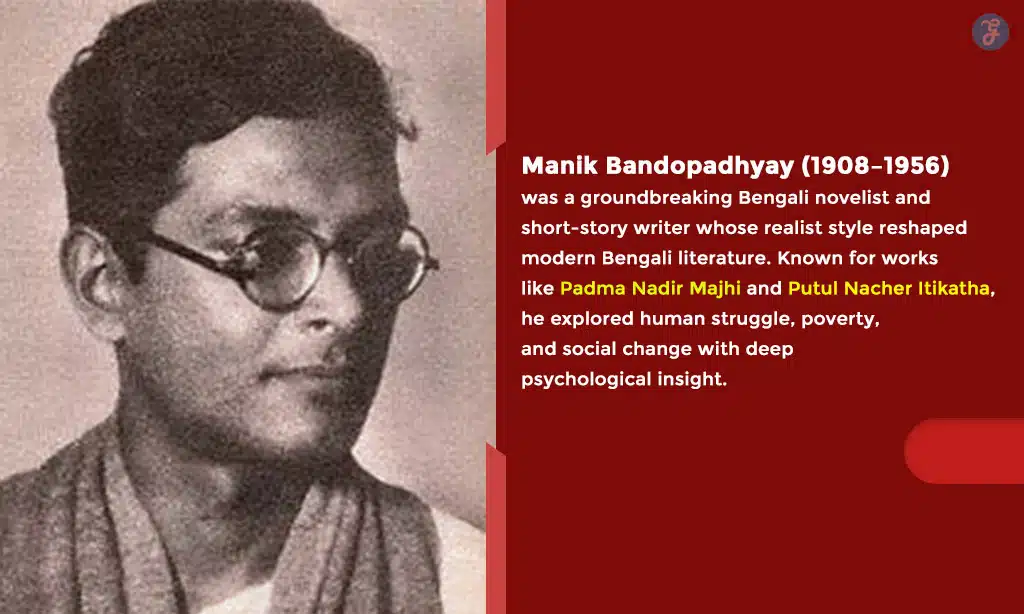

Manik Bandopadhyay (1908-1956) was not your typical storyteller. In fact, he started his literary career with a bet. As a student at Presidency College in Kolkata, he claimed he could get his first-ever story published in the prestigious Bichitra magazine. He won that bet with “Atasimami” in 1928, and Bengali literature was never the same again.

Unlike the romantic writers before him, Manik looked at the world with the cold, sharp eyes of a scientist. He didn’t just tell stories; he dissected the human mind to show us the raw struggles of ordinary people in 1930s India. From the mud-slicked banks of the Padma River to the quiet desperation of village doctors, his work reveals the hidden corners of our psychology.

In this guide, we are going to walk through exactly how Manik creates these unforgettable characters. We will look at the specific psychological tools he used and how you can spot them in his most famous works. So, grab a cup of tea, and let’s explore the brilliant, complex mind of Manik Bandopadhyay.

Key Takeaways

- He viewed life like a scientist: Manik Bandopadhyay broke away from romantic traditions to analyze characters with clinical detachment, often exposing the “reptilian” instincts hidden beneath civilized behavior.

- Realism meets Psychology: His stories, like Padma Nadir Majhi (1936) don’t just show poverty; they show how hunger and social oppression twist the human mind and shape our decisions.

- Freud and Marx are key: You will see clear influences of Sigmund Freud’s ideas on repressed desires (the Id) and Karl Marx’s theories on class struggle working together in his narratives.

- Characters are “Puppets”: In novels like Putulnacher Itikatha (The Puppet’s Tale), he explores how social rules and fate control us, leaving characters like Shashi feeling helpless despite their education.

- The “Dark” Side is normal: His fiction validates feelings of jealousy, greed, and forbidden attraction, showing them as natural parts of the human experience rather than just moral failings.

How Does Manik Bandopadhyay Explore Human Psychology in His Fiction

Manik Bandopadhyay digs into the minds of his characters with a precision that feels almost surgical. He does not stop at what a character does; he relentlessly questions why they do it. This approach was radical for his time because he refused to idealize village life.

Instead of painting a pretty picture of rural Bengal, he showed it as it really was: a place where survival is a daily battle. He used a technique often called “scientific realism.” This means he observed his characters—beggars, boatmen, intellectuals—without judging them, much like a biologist observing specimens in a lab.

For example, in his short story Pragoitihasik (Prehistoric), published in 1937, he introduces us to Bhikhu, a bandit. Rather than portraying Bhikhu as a romantic outlaw, Manik strips him back to his most primitive instincts. He shows how pain, hunger, and fear can reduce a human being to a state of raw, animalistic survival. This wasn’t done to shock readers but to reveal the “prehistoric” nature that still lurks inside civilized humans.

“Manik Bandopadhyay does not sugarcoat reality. He forces us to look at the hunger, lust, and greed that society tries to hide, proving that these ‘ugly’ emotions are just as real as love or sacrifice.”

He creates this depth by focusing on the “stream of consciousness.” In many of his stories, you hear the character’s internal monologue. You witness their uncertainties and their impulsive choices. This connects you to their pain and dreams in a way that feels personal, because you aren’t just watching them; you are thinking with them.

Key Psychological Themes in Manik’s Works

Manik Bandopadhyay fills his novels and short stories with intense, conflicting emotions. His characters often face storms inside their minds, shaped by the harsh realities of their environment. You will find that his work consistently revolves around three major psychological pillars.

The Conflict Between Instinct and Social Duty

In Putulnacher Itikatha (1936), the protagonist Shashi is a village doctor who feels trapped. He is educated and rational, yet he cannot escape the “puppet dance” of village customs and family expectations. His mind battles between his desire to leave and his inexplicable duty to stay.

Similarly, in “Atasimami,” the character Atasi clings to a memory of love that defines her entire existence. Her grief isn’t just sadness; it is a psychological anchor that keeps her grounded in a changing world. Manik shows us that sometimes, our internal commitments are stronger than any external law.

The Impact of Poverty on the Psyche

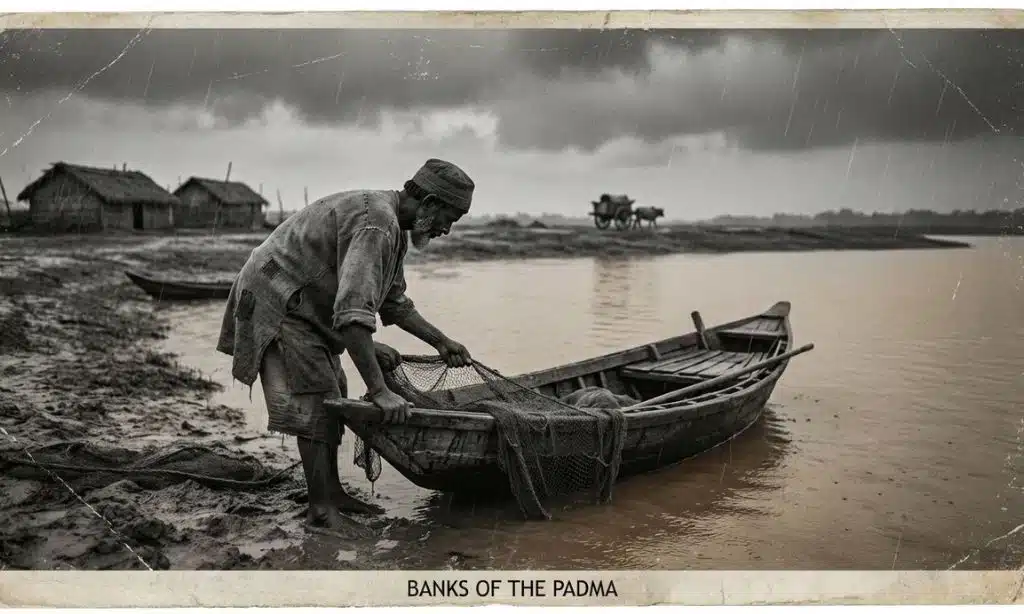

Social realism is the bedrock of Manik’s psychology. He understood that you cannot separate a person’s mind from their stomach. In Padma Nadir Majhi, the boatman Kuber isn’t just “sad” because he is poor. The constant threat of hunger rewires his brain.

He becomes willing to take risks, like smuggling for the mysterious Hossain Miya, not because he is a criminal at heart, but because poverty has narrowed his moral choices. The anxiety of survival creates a specific type of mental resilience—and exhaustion—that Manik captures perfectly.

Loneliness and Alienation

Why do so many of his characters feel alone even when they are surrounded by people? Manik himself faced significant struggles, including epilepsy and financial hardship, which likely influenced his writing. He creates “outsider” characters who see the hypocrisy of society and feel cut off from it.

Shashi in Putulnacher Itikatha is the ultimate example. He watches the villagers’ dramas with a detached, lonely gaze, unable to fully participate or look away. This theme of alienation speaks to anyone who has ever felt like they didn’t quite fit in with their community.

Psychological Theories Influencing Manik’s Writing

You can’t talk about Manik Bandopadhyay without mentioning the two giants of thought who influenced him: Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx. He had a unique ability to blend these two seemingly different viewpoints into a single narrative.

How did Freud’s ideas shape Manik’s characters?

Sigmund Freud’s theories about the unconscious mind are everywhere in Manik’s fiction. Freud believed that human behavior is driven by hidden desires (the Id) that conflict with social rules (the Super-Ego). Manik uses this to show the “forbidden” thoughts we all have.

Take Kuber in Padma Nadir Majhi. He is a married man with children, yet he feels a magnetic, undeniable pull toward Kapila, his sister-in-law. Manik doesn’t portray this as a simple affair; he writes it as a collision of primal desire against social structure. Kuber’s internal struggle is a classic Freudian battle where his “Id” wants Kapila, while his social conscience tries to suppress it.

The Marxist Lens on Psychology

While Freud explained the individual mind, Marx explained the society that crushes it. Manik joined the Communist Party of India in 1944, but his class consciousness was present long before that. He shows how economic systems create psychological trauma.

For the boatmen on the Padma River, the feudal oppression they face doesn’t just empty their pockets; it robs them of their agency. They develop a psychology of dependence on figures like Hossain Miya, who represents both a savior and an exploiter. This mix of fear and gratitude is a direct result of their class position.

| Theory | Focus in Manik’s Work | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Freudian Psychoanalysis | Repressed sexual desires and primal instincts. | Bhikhu in Pragoitihasik acting on raw impulse. |

| Marxist Social Realism | How poverty and class determine mental state. | The boatmen in Padma Nadir Majhi relying on Hossain Miya. |

What Psychological Traits Define Manik’s Notable Characters

Manik’s characters stick with you because they are complex. They aren’t heroes or villains; they are survivors. Let’s look closely at two of his most famous creations to see how he builds this psychological depth.

The Detached Observer: Shashi in “The Puppet’s Tale”

In Putulnacher Itikatha, Shashi stands out as one of the most tragic figures in Bengali literature. He is a doctor, a man of science in a village of superstition. His defining trait is his detachment. He sees the “strings” that control everyone else—the caste rules, the petty feuds, the blind faith—but he cannot cut them.

Shashi knows that his life in the village is a waste of his potential, yet he stays. This isn’t laziness; it’s a paralysis caused by seeing too much. His psychology is that of the intellectual who is alienated by his own knowledge. He represents the tragedy of knowing you are a puppet but being unable to leave the stage.

The Survivor: Kuber in “The Boatman of the Padma”

Kuber is the opposite of Shashi. He is not an intellectual; he is a man of action and instinct. His psychological trait is resilience. Living on the edge of the river, which can destroy his home in an instant, Kuber has developed a mind that lives only in the present.

He fears Hossain Miya, the man who wants to take him to the remote island of Moynadwip. Yet, he is also drawn to the promise of a new life there. Kuber’s mind is constantly weighing the known danger of the village against the unknown danger of the island. This constant state of high-stakes gambling with his own life defines his character.

How Do Manik’s Characters Reflect Aspects of Human Nature

Manik Bandopadhyay’s stories are a mirror. When you look at his characters, you often see the parts of human nature we try to ignore. He teaches us that resilience isn’t always pretty, and moral choices are rarely black and white.

Nature vs. Nurture in Rural Bengal

His characters show us that human nature is adaptable. In stories like Sahartoli (Suburbia), we see people from rural areas moving to the city fringes. Manik documents how their nature changes—they become more calculating and cynical to survive in the urban chaos.

But in the villages, like in Padma Nadir Majhi, nature is physical. The storm (Kalbaishakhi) is a character itself. The boatmen respect the river more than the law because the river has immediate power over their lives. This reflects a human truth: we respect what can destroy us.

The Moral Gray Zone

Manik forces his characters to make impossible choices. Is it wrong for Kuber to steal when his children are starving? Is it wrong for Kapila to flirt with Kuber when her own marriage is miserable? Manik doesn’t answer these questions for you.

He presents the situation and lets you decide. Most of the time, you realize that “right” and “wrong” are luxuries that the poor cannot always afford. This moral ambiguity is perhaps the most realistic aspect of his psychology. It reminds us that under enough pressure, anyone might make choices they never thought possible.

Takeaways

Manik Bandopadhyay changed the landscape of Indian literature by refusing to look away. He took the “scientific” gaze of a doctor and applied it to the human soul, revealing the complex machinery of greed, love, fear, and survival that drives us all.

His characters, from the conflicted Shashi to the resilient Kuber, remind us that we are all shaped by forces we can’t always control. Whether it’s the strings of society or the storms of the Padma River, his stories capture the beautiful, tragic struggle of being human.

FAQs on Human Psychology in Manik Fiction

1. How does Manik Bandyopadhyay explore human psychology in his Bengali fiction?

He explores the human mind by blending Freudian analysis with Marxist views, often highlighting internal conflicts like those of Shashi in Putul Nacher Itikatha. You will find he exposes raw instincts like hunger and desire to show people exactly as they are.

2. What role does realism play in Manik’s short stories?

Realism anchors his writing, as he steps away from romanticized village life to depict the gritty reality of East Bengal’s marginalized communities. In classics like Padma Nadir Majhi, he uses authentic dialects to show the harsh survival battles fishermen face every day.

3. How did history shape Manik Bandyopadhyay’s characters?

Major historical events like the Bengal Famine of 1943 and the rise of the Communist Party of India directly shaped his focus on class struggle and social inequality.

4. Why do readers connect with characters from Bengali literature written by Manik?

Readers resonate with these stories because he presents the honest and often uncomfortable truths of the human condition. His characters deal with universal issues like poverty and moral dilemmas, making their experiences feel personal to anyone reading them.