Hubble sees asteroids colliding in the nearby Fomalhaut system—an event captured as a new point of light in 2023 that researchers say marks a fresh, massive smashup, and strengthens the case that the system’s once-hyped “planet” was actually debris from an earlier collision.

A rare “point of light” appears—then rewrites a long-running mystery

Astronomers studying the bright star Fomalhaut, about 25 light-years away, say they have directly observed the aftermath of a catastrophic collision between two large bodies—something long suspected to shape young planetary systems, but rarely caught “in the act.”

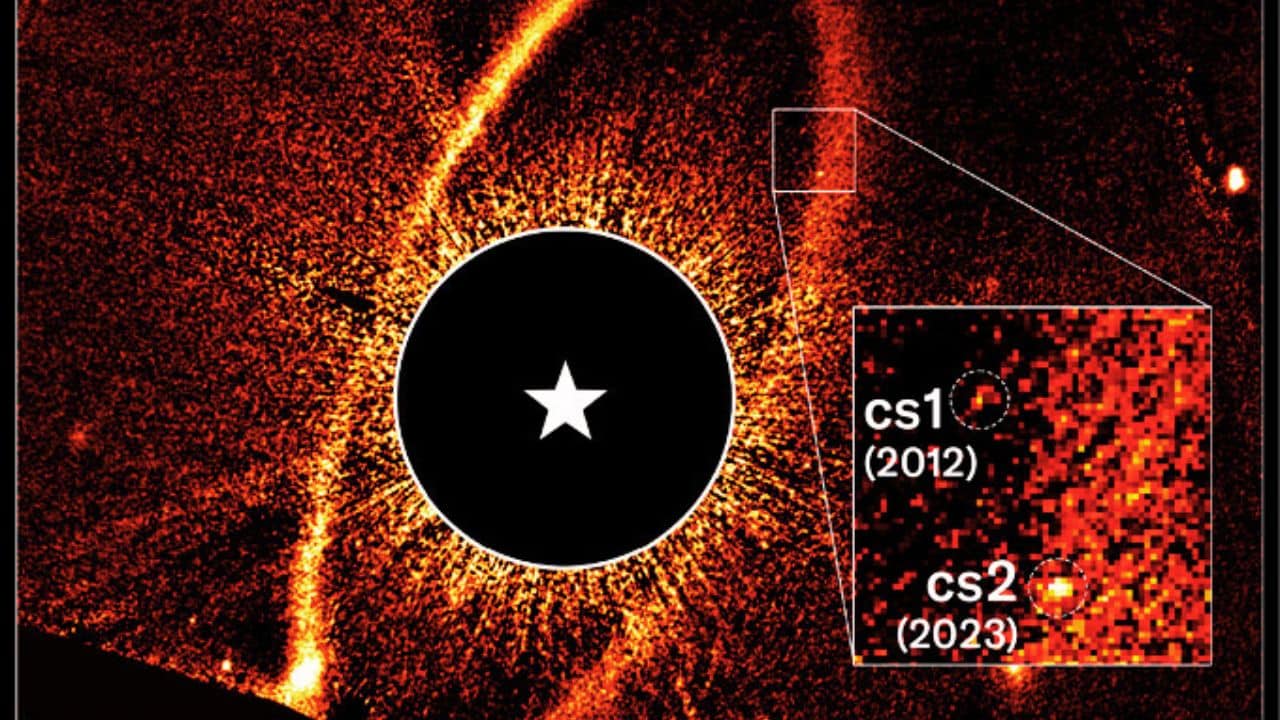

In September 2023 observations, a previously unseen point source appeared near the inner edge of Fomalhaut’s debris belt. Researchers labeled the new feature Fomalhaut cs2 (short for “circumstellar source 2”) and interpret it as a rapidly expanding dust cloud created by a recent impact.

That “new light” matters because it closely resembles an earlier mystery object—first imaged in the mid-2000s and popularly known for years as Fomalhaut b, a candidate exoplanet announced in 2008.

What is Fomalhaut—and why this system is watched so closely

Fomalhaut is one of the brightest stars visible from Earth, located in the constellation Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish). It is surrounded by belts of dusty debris—leftovers from planet formation—where countless smaller bodies can collide.

Those debris belts act like a forensic scene: dust reflects starlight, and its shapes and brightness can hint at unseen planets and ongoing impacts.

From “first visible-light planet snapshot” to “vanishing planet”

The earlier source—Fomalhaut b—was based on Hubble images taken in 2004 and 2006 and announced publicly in 2008. But it never behaved like a typical directly imaged planet: it appeared unusually bright in visible light and lacked the expected infrared heat signature.

By 2014, the object could no longer be seen in Hubble data, and researchers proposed that it was not a planet at all, but a vast, expanding dust cloud produced by a collision between large bodies orbiting within the debris ring.

A 2020 analysis argued that the dust cloud’s fading and expansion fit better than a planet explanation, estimating the debris would have expanded to a scale larger than Earth’s orbit and eventually fallen below Hubble’s detection limits.

The 2023 event: “cs2” shows up where it shouldn’t

The new 2023 feature (cs2) was detected in deep Hubble imaging designed to search for the earlier object—only to find something else. Researchers reported that cs2 was absent in all previous Hubble images, meaning it appeared sometime after the last sensitive Hubble look in 2014.

A follow-up Hubble observation in September 2024 had lower sensitivity, but showed a possible faint source near the 2023 position—consistent with the system changing over time.

Why scientists say this is “the first time” we’ve caught it

Collisions are believed to be central to how planetary systems evolve, especially early on. But directly seeing the debris from a large impact around another star is extremely difficult: the dust is faint, close to a dazzling star, and changes over time.

The current studies frame this as a milestone because Hubble directly imaged what looks like catastrophic collisions in an exoplanetary system—essentially catching a major dust-producing event as it appeared.

What exactly collided—and how big were the objects?

Based on the brightness of the dust clouds and models of dust production, researchers estimated the destroyed bodies that produced cs1 (the former “Fomalhaut b” source) and cs2 were on the order of ~60 kilometers (37 miles) across.

They also inferred a surprisingly large population of similar-sized objects in the disk—on the order of hundreds of millions—highlighting how active and crowded the system may be.

Key data at a glance: cs1 vs cs2

| Feature | cs1 (formerly “Fomalhaut b”) | cs2 (new dust cloud) |

| First prominent detection | Mid-2000s Hubble imaging | Hubble imaging in 2023 |

| Interpretation today | Dust cloud from a collision | Dust cloud from a collision |

| Notable behavior | Faded and was not detected in 2014 | Appeared after 2014 |

| Representative Hubble epoch shown | 2012 | 2023 |

| Estimated collider size | ~60 km class bodies | ~60 km class bodies |

The bigger picture: why this matters for finding other worlds

Dust clouds can masquerade as planets

One key takeaway is that dust clouds like cs1 and cs2 can look like compact “dots” in visible-light images—potentially fooling planet-hunting efforts that rely on direct imaging. Researchers say this is a caution for future missions that aim to photograph Earth-like worlds: not every dot is a planet.

A real-time laboratory for early solar-system chaos

Scientists compare what’s happening around Fomalhaut to the violent early era of our own solar system, when impacts were common and helped shape planets and moons. The Fomalhaut system’s activity offers a rare chance to test models of how belts of planetesimals grind down over time and how dust is produced and pushed outward by starlight.

More monitoring is underway

Follow-up work is continuing with Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope to watch how the aftermath evolves and to better constrain the impact timing and the dust properties.

Timeline: how the story developed (2004–2025)

| Year/Date | What happened | Why it mattered |

| 2004–2006 | Hubble sees a point source near Fomalhaut’s debris belt | Sparked the idea of a directly imaged planet candidate |

| 2008 | “Fomalhaut b” announced | Widely treated as a landmark visible-light exoplanet candidate |

| 2014 | Source not detected in Hubble data | Raised major doubts about the “planet” interpretation |

| Apr 20, 2020 | Analysis argues the object is a dust cloud from a collision | Reframed the mystery as impact debris, not a planet |

| Sep 2023 | Hubble detects a new point source (cs2) | Fresh evidence of a second major collision |

| Dec 18, 2025 | New study and releases highlight the finding | Consolidates cs1/cs2 as collision debris and discusses implications |

Takeaways and what comes next

Fomalhaut’s “disappearing planet” story is no longer just a cautionary tale—it is now evidence of multiple large-scale collisions in one nearby system, observed across two decades. The appearance of cs2 in 2023 strongly supports the idea that the earlier source (cs1) was also impact debris, not a stable, self-luminous planet.

Next, astronomers will be watching whether cs2 expands, fades, or shifts position in ways that further constrain the impact timing, the dust grain sizes, and the dynamics of the debris belt—and using those lessons to sharpen how future direct-imaging searches separate true planets from look-alike dust events.