As of January 2026, the fragile trilateral balance between Nuuk, Copenhagen, and Washington has fractured into a high-stakes standoff.1 Following the collapse of the Washington Summit earlier this month, the U.S. demand for exclusive “strategic pre-emption” rights over Greenland’s rare earth sector in exchange for a historic aid package has been met with a unified—but precarious—rejection from Danish and Greenlandic leadership. This is no longer just about purchasing an island; it is about who controls the “Suez of the North” in a post-ice Arctic.

Key Takeaways

- Diplomatic Breakdown: The January 2026 trilateral talks ended without a joint communiqué after the U.S. conditioned continued defense guarantees on exclusive mining rights, effectively challenging the 1951 Defense Treaty.

- Resource Race: With China restricting 90% of heavy rare earth exports as of late 2025, Greenland’s Tanbreez and Kvanefjeld deposits have become the single most critical supply chain pivot for U.S. national security.

- Sovereignty Paradox: Greenland’s pro-independence government faces a “Golden Handcuff” dilemma: the U.S. offer provides the financial independence needed to leave Denmark, but at the cost of becoming a de facto U.S. protectorate.

- Militarization: The Pentagon has unilaterally approved a $4 billion expansion plan for Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule) to counter Russian hypersonic glide vehicles, bypassing standard consultation protocols with Nuuk.

The Anatomy of the Crisis

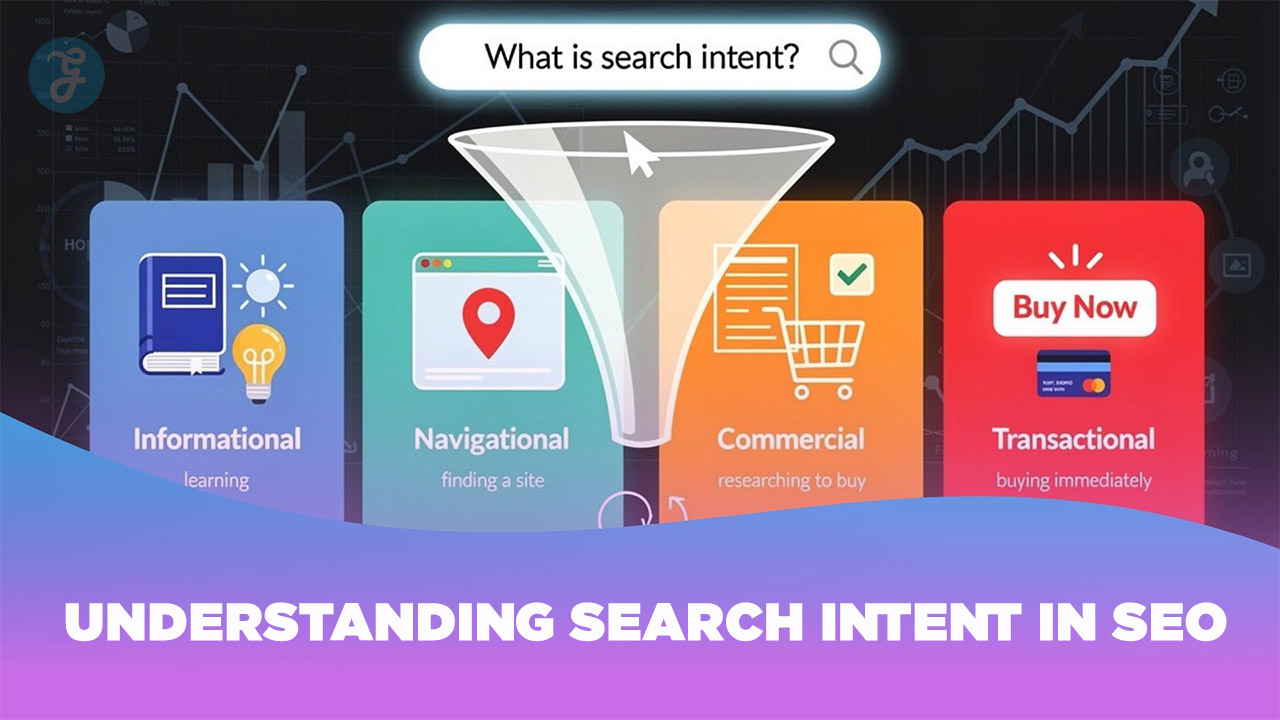

The current deadlock is not a sudden event but the culmination of a three-year diplomatic erosion. While the initial 2019 proposal to “purchase” Greenland was dismissed as an absurdity, the 2025-2026 strategy has evolved into a sophisticated geopolitical siege. The U.S. administration, citing the “Monroe Doctrine of the Arctic,” argues that a Greenland reliant on Danish subsidies—and by extension, open to Chinese infrastructure bids—is an unacceptable security vulnerability in the Western Hemisphere.

In late 2025, the U.S. State Department tabled the “Arctic Economic & Security Compact” (AESC). The Compact offered a direct $10 billion annual investment in Greenlandic infrastructure and education—roughly 15 times the current Danish block grant. In return, Washington demanded:

- Veto power over any foreign investment in critical infrastructure.

- Exclusive rights for U.S. and allied firms to bid on rare earth projects.

- Expanded extraterritorial jurisdiction around U.S. military installations.

Nuuk’s rejection of these terms on January 14, 2026, triggered the current impasse.

Five Dimensions of the Deadlock

1. The Rare Earth “Kill Switch”

The deadlock is fundamentally driven by geology. As of 2026, the global shortage of Dysprosium and Terbium (essential for EV motors and guided missiles) has reached crisis levels due to new Chinese export quotas. Greenland holds an estimated 38.5 million tonnes of rare earth oxides.

- The Conflict: The U.S. views these deposits as strategic assets akin to uranium in the 1940s. It cannot tolerate a scenario where a newly independent Greenland grants mining concessions to state-backed Chinese entities (like Shenghe Resources) to shore up its budget.

- The Reality: Greenland wants to auction these rights to the highest bidder to fund its independence. The U.S. demand for “exclusivity” forces Greenland to sell below market value, essentially subsidizing U.S. defense needs with Greenlandic resources.

2. The Pituffik Power Play

Alt Text: Map of the Arctic showing military reach from Pituffik Space Base compared to Russian and Chinese activity.

Pituffik Space Base is the eyes and ears of U.S. missile defense.2 However, the 2026 upgrade plan involves deploying new long-range hypersonic tracking sensors that require significant land expansion.

- Sovereignty Issue: Under the 2009 Self-Rule Act, Nuuk has a say in foreign policy affecting domestic affairs. The U.S. argues that missile defense is a “global” necessity that supersedes local objections, effectively treating Greenlandic soil as U.S. federal territory.

3. The Economic “Golden Handcuffs”

The U.S. offer puts Greenland’s premier, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, in an impossible position. The table below illustrates the stark economic reality facing the independence movement.

The Independence Budget Gap (2026 Estimates)

| Funding Source | Annual Value (USD) | Political Cost | Risk Level |

| Danish Block Grant | $600 Million | Continued dependence on Copenhagen; delayed independence. | Low |

| Current Mining Rev. | $150 Million | Insufficient to cover social services. | Medium |

| U.S. AESC Proposal | $10 Billion | Loss of foreign policy autonomy; U.S. veto on trade. | High |

| Chinese Investment | Varies ($2-5B est.) | U.S. sanctions; NATO security crisis. | Extreme |

4. The NATO Fracture

Denmark is the silent loser in this deadlock. Copenhagen cannot match the U.S. financial offer, nor can it forcefully defend Greenland’s sovereignty without alienating its most important security partner.

- The Wedge Strategy: Washington has increasingly bypassed Copenhagen, speaking directly to Nuuk. This undermines the “Unity of the Realm” and signals to other Arctic nations that the U.S. no longer views Denmark as the gatekeeper to the Arctic.

5. Climate Sovereignty vs. Security

A nuanced layer of the deadlock is the clash between U.S. industrial ambitions and the Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) party’s environmental stance. The U.S. push for rapid, large-scale extraction conflicts with local bans on uranium mining and strict environmental protocols. The U.S. administration has labeled these environmental protections as “strategic obstructions,” hinting that they serve adversarial interests by keeping resources in the ground.

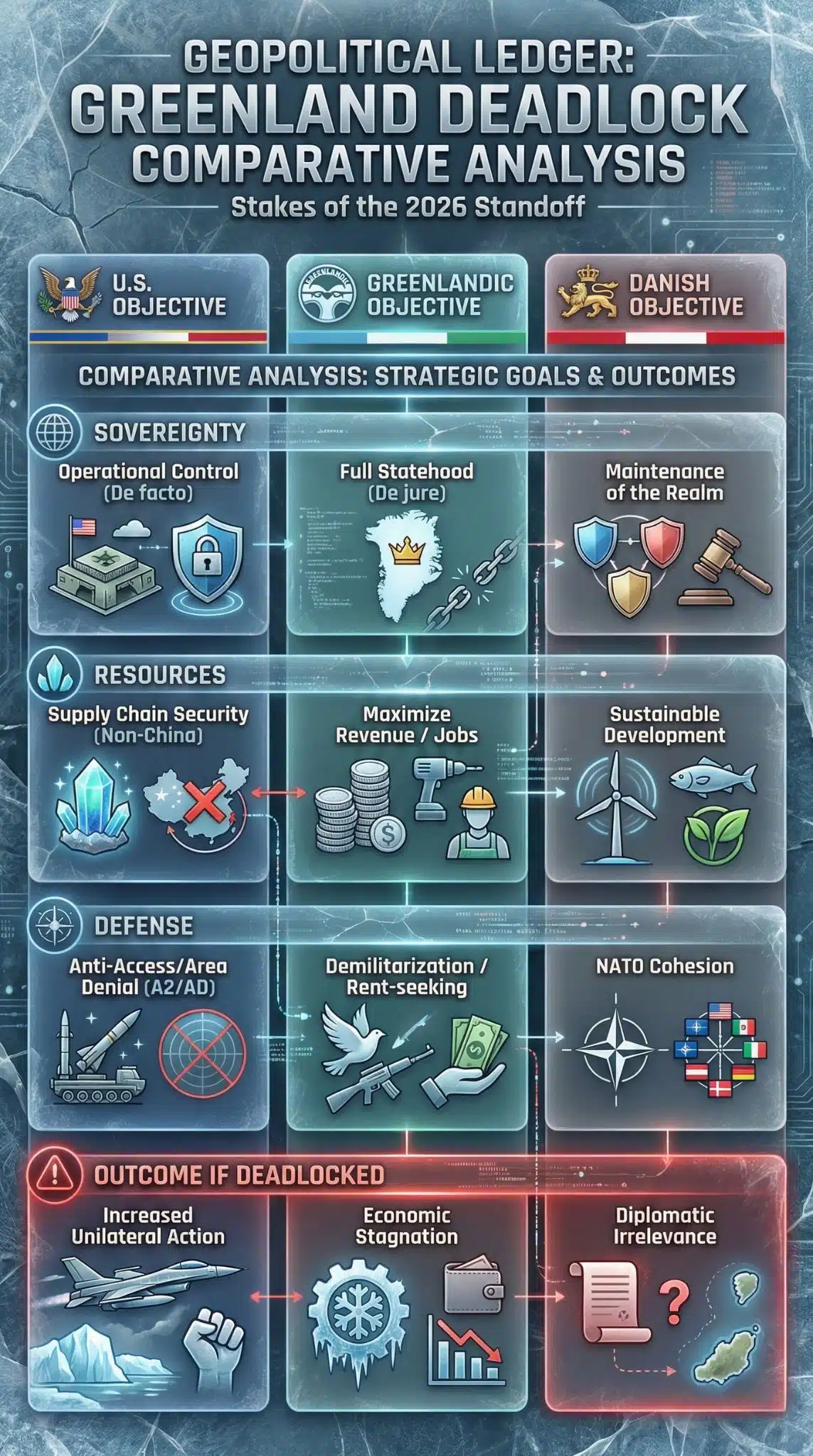

Comparative Analysis: The Geopolitical Ledger

To understand the stakes, we must look at the winners and losers if the current deadlock persists or resolves in favor of the U.S.

Strategic Outcomes of the Deadlock

| Strategic Goal | U.S. Objective | Greenlandic Objective | Danish Objective |

| Sovereignty | Operational control (De facto) | Full Statehood (De jure) | Maintenance of the Realm |

| Resources | Supply chain security (Non-China) | Maximize revenue / Jobs | Sustainable development |

| Defense | Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) | Demilitarization / Rent-seeking | NATO cohesion |

| Outcome if Deadlocked | Increased unilateral action | Economic stagnation | Diplomatic irrelevance |

Expert Perspectives

“We are witnessing the end of the ‘Low Tension’ Arctic. The U.S. isn’t negotiating for a base anymore; they are negotiating for a unsinkable aircraft carrier the size of Western Europe. For Greenland, the choice is between being a Danish county or an American territory. True independence is evaporating.” — Dr. Elena Kogan, Senior Fellow at the Arctic Institute for Security Policy.

“The economic logic is brutal. Nuuk cannot afford independence on fish alone. The U.S. knows this. They are waiting for the financial pressure to force the Greenlandic parliament to capitulate. It’s checkbook diplomacy with a military hammer.” — Lars Mikkelgaard, Arctic Economist, University of Copenhagen.

Future Outlook: What Comes Next?

The deadlock is unlikely to hold through the summer of 2026. Three potential triggers could force a resolution:

- The June Election: If the deadlock causes a budget crisis in Nuuk, a snap election could bring a populist pro-U.S. faction to power, or conversely, a hardline anti-mining coalition that shuts down talks entirely.

- Unilateral U.S. Action: The U.S. State Department may invoke “Emergency National Security” provisions to bypass local environmental laws for the Tanbreez mine, daring Nuuk to physically stop U.S. engineers.

- The “Iceland Model” Compromise: A potential third way is emerging—a “Free Association” status where Greenland delegates defense explicitly to the U.S. (bypassing Denmark) in exchange for direct payments, while retaining domestic autonomy.3

Final Words

The Greenland Deadlock is the first major test of the new Arctic order. The era of the Arctic as a “zone of peace” is officially over. The question for 2026 is not whether Greenland will be militarized and mined, but whose flag will fly over the silos and shafts.