The delivery of the first commercial-scale shipment of hydrogen-produced steel represents the end of the “pilot phase” and the beginning of the industrial decarbonization era. With the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entering its definitive phase this month (January 2026), this breakthrough proves that heavy industry can decouple from fossil fuels, fundamentally altering the economics of construction, automotive manufacturing, and global trade.

Key Takeaways

- Commercial Reality: The sector has graduated from “prototypes” to “traded commodity.” The shipment by the German-Swedish consortium (led by Stegra, formerly H2 Green Steel) marks the first volume delivery to meet full commercial specifications.

- Policy Catalyst: The timing is deliberate. As of January 1, 2026, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) forces importers to pay for embedded carbon, eroding the price advantage of “dirty” steel from non-EU competitors.

- The “Green Premium” Shift: While green steel currently costs 25-30% more than traditional steel, the gap is rapidly closing due to rising carbon taxes on conventional producers.

- Supply Chain Ripple: The construction and automotive sectors are aggressively securing long-term contracts (offtake agreements), anticipating a supply bottleneck for fossil-free materials through 2030.

From Lab Experiments to Industrial Giants

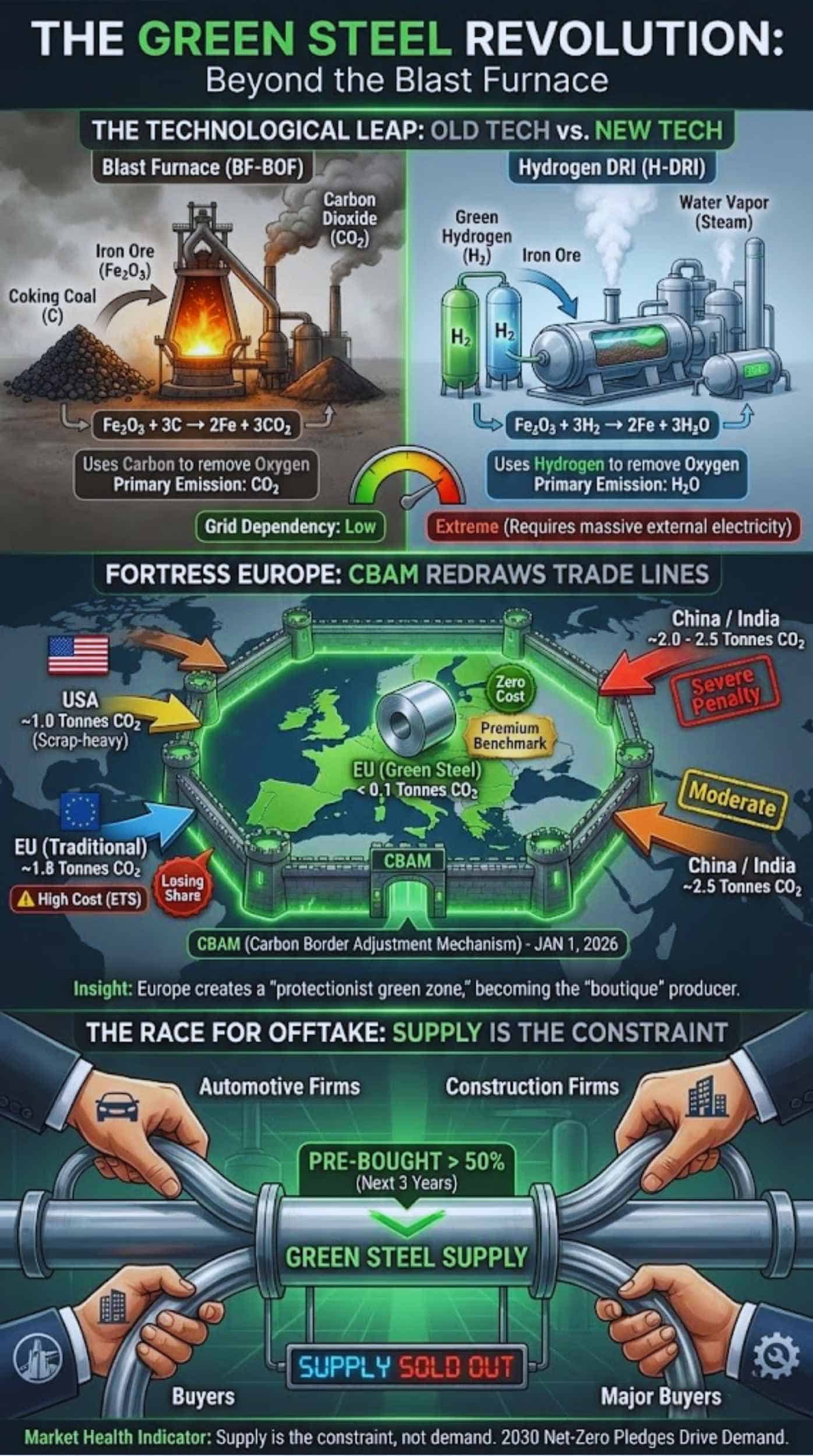

To understand yesterday’s announcement, we must look back at the “carbon lock-in” that has defined the steel industry for a century. Traditional blast furnaces, which use coking coal to strip oxygen from iron ore, are responsible for approximately 7-9% of global CO2 emissions. For decades, this was considered a “hard-to-abate” sector, immune to the electrification that transformed other industries.

The turning point began around 2016 with the launch of the HYBRIT initiative (SSAB, LKAB, Vattenfall) and the subsequent emergence of challengers like Stegra (founded as H2 Green Steel in 2020). These projects wagered on Hydrogen Direct Reduction (H-DRI)—a process that uses green hydrogen instead of coal, emitting water vapor rather than carbon dioxide.

By 2024, the industry saw massive capital injections, with Stegra securing over €6.5 billion in funding. Yesterday’s shipment marks the successful navigation of the “valley of death,” proving that fossil-free steel can be produced not just in a lab, but at a volume capable of supporting commercial supply chains like those of Mercedes-Benz and Scania.

The Economics of 2026 – When the ‘Green Premium’ Becomes the Standard

The most immediate question for the market is cost. As of early 2026, green steel still carries a “green premium,” but the definition of “expensive” is changing. High-end buyers are no longer viewing this as a charitable donation to the climate, but as a hedge against regulatory inflation.

Cost Structure Comparison (2026 Estimates)

| Cost Component | Traditional Steel (Blast Furnace) | Green Steel (Hydrogen DRI-EAF) | Trend Analysis (2026-2030) |

| Primary Reductant | Coking Coal (~$250/tonne) | Green Hydrogen (~$4-5/kg) | Coal is volatile; Hydrogen costs are falling as electrolyzers scale. |

| Energy Source | Fossil Fuels (Coal/Gas) | Renewable Electricity (Wind/Hydro) | Green steel is highly sensitive to grid electricity prices (PPA contracts). |

| Carbon Cost (EU ETS) | ~€100 per tonne of CO2 | ~€0 (Exempt) | As free allowances fade, traditional steel costs rise by ~€200/tonne. |

| Capital Expenditure | Depreciated Assets (Paid off) | High (New Electrolyzers/Plants) | Green steel has high debt servicing costs initially. |

| Total Production Cost | €600 – €700 / tonne | €800 – €950 / tonne | Gap narrowing: The 25% premium shrinks as carbon taxes bite. |

Insight: The “Green Premium” is currently €150-250 per tonne. However, for a luxury vehicle like a Porsche or Mercedes, this adds less than €500 to the total manufacturing cost of a €100,000 car—a negligible amount for the brand value it delivers.

Beyond the Blast Furnace – The H-DRI Industrial Revolution

The shipment confirms the viability of the Hydrogen Direct Reduction Iron (H-DRI) process combined with Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF). Unlike the gradual “efficiency improvements” of the past decade, this is a total technological replacement.

The Technological Leap

| Feature | Old Tech: Blast Furnace (BF-BOF) | New Tech: Hydrogen DRI (H-DRI) |

| Chemical Process | Uses Carbon (C) to remove Oxygen (O) from Iron Ore ($Fe_2O_3$). | Uses Hydrogen ($H_2$) to remove Oxygen. |

| Chemical Reaction | $Fe_2O_3 + 3C \rightarrow 2Fe + 3CO_2$ | $Fe_2O_3 + 3H_2 \rightarrow 2Fe + 3H_2O$ |

| Primary Emission | Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | Water Vapor (Steam) |

| Grid Dependency | Low (Self-generates gases) | Extreme (Requires massive external electricity) |

| Flexibility | Continuous operation (hard to stop) | Can ramp up/down with hydrogen storage buffers. |

Why it matters: The success of this shipment validates the reliability of large-scale electrolyzers (such as the 700MW units used by Stegra) operating in a fluctuating industrial grid. Skeptics argued that intermittent wind power couldn’t run a steel mill; this shipment proves that hydrogen buffers work.

Fortress Europe – How CBAM is Redrawing Trade Lines

This breakthrough cannot be viewed in isolation from the geopolitical wall Europe has just erected. As of January 1, 2026, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has entered its definitive phase.

The CBAM Effect on Steel Imports (2026 Status)

| Exporter Region | Carbon Intensity (Tonnes CO2/Tonne Steel) | CBAM Impact (2026) | Market Consequence |

| EU (Green Steel) | < 0.1 | Zero Cost | Becomes the benchmark for “Premium” grade. |

| EU (Traditional) | ~1.8 | High Cost (ETS) | Losing share to green steel & cheap imports (if not protected). |

| China / India | ~2.0 – 2.5 | Severe Penalty | Must pay the difference between local carbon price and EU price. |

| USA | ~1.0 (Scrap-heavy) | Moderate | US steel is cleaner than China’s but still faces reporting burdens. |

Insight: Europe is effectively creating a “protectionist green zone.” By mastering green steel technology first, Europe is positioning itself as the “boutique” producer of high-grade materials, leaving commodity-grade, coal-based steel production to regions that can no longer easily export to the EU without paying a penalty.

The Race for Offtake – Who is Buying the Supply?

The most telling indicator of the market’s health is the “Offtake War.” In 2026, supply is the constraint, not demand. Major automotive and construction firms have pre-bought over 50% of the projected capacity for the next three years to ensure they can meet their 2030 net-zero pledges.

Major Green Steel Offtake Agreements (2026 Snapshot)

| Buyer | Industry | Primary Supplier Partner | Volume / Commitment | Strategic Goal |

| Mercedes-Benz | Automotive | Stegra (H2 Green Steel) | ~50,000 tonnes/year | Launch “Green Steel” models by 2027. |

| Volvo Group | Trucks/Heavy | SSAB / Stegra | First priority access | Zero-emission truck frame manufacturing. |

| Scania | Trucks/Heavy | Stegra | Commercial volumes | Decarbonize supply chain by 2030. |

| IKEA | Consumer Goods | Stegra | Warehouse Racking | Reduce Scope 3 emissions in retail operations. |

| Porsche | Luxury Auto | Stegra | Niche high-strength steel | Brand differentiation for high-performance EVs. |

Insight: The involvement of non-automotive players like IKEA and construction giant Skanska signals that green steel is moving beyond cars into the wider built environment.

The Energy Dilemma – The “Silent” Crisis

The “silent partner” in this success story is electricity. Producing enough hydrogen for this single shipment required gigawatt-hours of fossil-free electricity. As production ramps up later this year, the strain on the Nordic and German power grids will intensify.

- The TWh Challenge: To produce just 5 million tonnes of green steel (a fraction of Europe’s 150m tonne output), the industry needs roughly 10-12 TWh of renewable electricity. That is equivalent to the annual consumption of over 1 million households.

- The Conflict: There is a genuine risk that steel mills will compete with cities and data centers for renewable power, potentially driving up regional electricity prices in Northern Sweden and Germany. This has already sparked local political debates about wind farm permitting.

The Optimists vs. The Realists

To ensure a balanced view, we analyzed insights from varying industry voices in 2026:

The Optimist:

“This is the ‘Tesla moment’ for heavy industry. Just as electric cars went from novelty to inevitable, hydrogen steel has now proven it can meet industrial specifications at scale. The premium will vanish by 2030 as carbon taxes rise.”

— Dr. Elena Weber, Industrial Decarbonization Lead, Berlin Energy Forum.

The Grid Realist:

“The technology works, but the math is difficult. To replace just 10% of European steel with this method, we would need to dedicate nearly 20% of our current renewable energy capacity to hydrogen production. We are solving a steel problem but potentially creating an energy price crisis.”

— Tomasz Kowalski, Senior Energy Analyst, Warsaw Institute of Strategic Studies.

The Trader:

“We are seeing a bifurcation of the market. There will be ‘Green Steel’ for European cars and buildings, and ‘Grey Steel’ for the rest of the world. The trade walls going up in 2026 will make these two distinct commodities with different tickers on the exchange.”

— Sarah Jenkins, Commodities Strategist, London Metal Exchange (LME).

Future Outlook: What Comes Next?

As we look toward the remainder of 2026 and beyond, three critical trends will define the trajectory of green steel:

- The “Green Iron” Trade Splits the Supply Chain: We may see a geographical split. Countries with abundant solar/wind (like Spain, Namibia, or Brazil) will produce “Green Sponge Iron” (the raw intermediate) and ship it to Germany for final processing into steel. This decouples the energy-intensive hydrogen step from the manufacturing step.

- Scramble for Scrap: Green steel production (EAF) relies heavily on high-quality scrap metal. Expect “Scrap Nationalism” where nations ban the export of recycled steel to keep it for their own green industries.

- Standardization Wars: Currently, every company defines “Green Steel” differently. In late 2026, expect the EU to enforce a legal definition (e.g., must be <300kg CO2/tonne) to prevent “greenwashing” where companies blend slightly cleaner steel and sell it as “green.”

Final Words

Yesterday’s shipment was more than just metal; it was proof of concept for the green industrial revolution. While challenges regarding cost and energy remain, the question is no longer if heavy industry can decarbonize, but how fast it can scale before the grid buckles under the demand. The “Green Steel” era has officially left the laboratory.