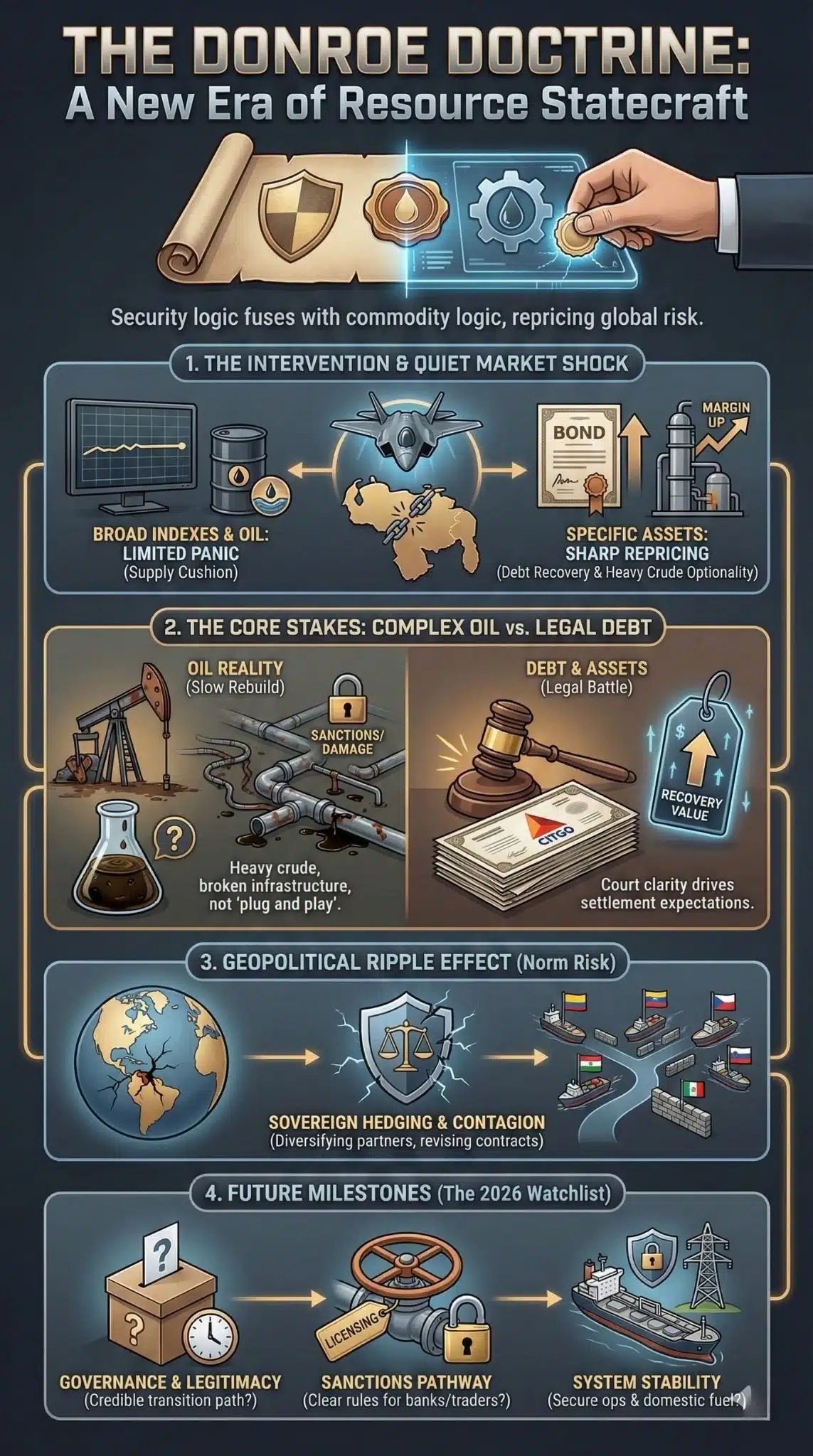

The Donroe Doctrine turned the early-January 2026 U.S. intervention in Venezuela into a stress test for oil logistics, sovereign-debt recoveries, and hemispheric power politics. The shock looked small in headline indexes, but it quietly repriced risk, refined the winners, and raised the odds of a new era of resource-focused statecraft.

How We Got Here: The Road From Sanctions To Seizure

Venezuela’s crisis did not begin with a raid. It was built over years of institutional breakdown, falling production capacity, capital flight, and a sanctions regime that steadily narrowed the country’s financial oxygen. By 2025, Venezuela’s oil story had shifted from “how big are its reserves” to “how damaged is its ability to monetize them.” That gap between geological wealth and operational reality is precisely why politics became the lever. When markets cannot model a country through normal policy tools, they start modeling it through regime odds.

Washington’s pressure campaign was already pushing in that direction. Sanctions constrained exports and finance, while law-enforcement narratives framed the leadership as a transnational security problem rather than a conventional political rival. That matters because it changes the legal and rhetorical threshold for action. “National security” language tends to expand the set of permissible tools, including maritime interdiction, targeted operations, and expanded partnerships with regional security forces.

The Donroe Doctrine is best understood as a branding of that shift. It evokes the Monroe Doctrine’s sphere-of-influence logic, but modernized for a world where border control, supply-chain resilience, and resource access sit alongside ideology. It is not simply “interventionism.” It is interventionism tied to economic outcomes, especially energy and logistics. Venezuela is the natural proving ground because its reserves are immense, its infrastructure is degraded, and its political legitimacy has been contested for years.

When the U.S. moved from pressure to direct intervention in early January 2026, the key change was not just leadership removal. It was the implied claim that Washington could shape the transition architecture, the sanctions timetable, and the investment pathway. That combination is why the market response was concentrated in very specific places, like distressed Venezuelan bonds, heavy-crude refining economics, and currencies sensitive to heavy-oil competition.

Key Statistics That Explain Why This Matters

- Proven crude reserves: ~303 billion barrels (among the largest globally).

- Crude quality: predominately heavy and extra-heavy, which requires specialized refining and often blending.

- CITGO footprint: ~829,000 barrels per day of refining capacity (strategic for U.S. downstream supply).

- PDV Holding bid: a U.S. court-approved bid reported at $5.9 billion, pending key approvals.

- Immediate price context: WTI in the high-$50s and Brent low-$60s in early January 2026, signaling limited broad panic.

- Debt-market signal: defaulted Venezuelan bonds trading in the low-40s cents on the dollar range as transition odds rose.

A Short Timeline Of The Escalation That Produced “Donroe” Pricing

| Date / Window | What Happened | Why Markets Cared |

| 2024–2025 | Sanctions and restricted finance tightened; production and infrastructure remained strained | Long-term supply optionality stayed depressed, and recovery paths became political |

| Late 2025 | Intensified pressure actions and visible regional security posture | Markets began pricing a higher probability of regime change |

| Nov–Dec 2025 | Court momentum around PDV Holding / CITGO parent ownership | Raised creditor recovery expectations and clarified a valuation anchor |

| Early Jan 2026 | U.S. intervention removes Maduro from power | Shifted risk from “sanctions stasis” to “transition governance and security” |

| First week Jan 2026 | Bonds rally, oil moves modestly, heavy-crude competition concerns appear | Shock concentrated in credit and downstream economics, not broad equities |

How The Donroe Doctrine Repriced Risk Without Crashing The Tape

One of the most revealing features of this episode is what did not happen. Global equity indexes did not collapse. Oil did not spike into triple digits. The reaction looked, at first glance, like an event that mattered mostly to diplomats and Venezuela specialists. That reading is tempting, and it is incomplete.

The Donroe Doctrine produced a modern kind of market shock: one that flows through micro-channels rather than through the whole system at once. There are three reasons.

First, the oil market entered 2026 with a cushion. Inventories and supply expectations can absorb a political jolt, at least temporarily, unless physical flows are disrupted at scale. Traders demand evidence of sustained disruption before pricing a major premium into benchmarks.

Second, modern geopolitics often reprices spreads and basis risk more than it reprices global indexes. If Venezuelan heavy crude becomes more available, the first-order effect is not “oil up everywhere.” The first-order effect is “which refiners benefit, which heavy grades lose pricing power, and how shipping and insurance reprice route risk.”

Third, the largest repricing was about option value, meaning the probability-weighted future of Venezuela’s oil sector and state assets. Markets can treat today’s uncertainty as manageable while still revaluing long-dated outcomes dramatically. That is exactly what distressed debt did.

What Moved First And Why

| Asset / Indicator | Early January 2026 Direction | Interpretation |

| WTI and Brent | Modest rise | Risk premium exists, but global supply cushion limits panic |

| Venezuelan defaulted bonds | Sharp rally | Higher expected recovery value under a transition scenario |

| Heavy-oil sensitive FX (example: CAD) | Underperformed | Fear of Venezuelan heavy crude competing with Canadian barrels |

| U.S. Gulf refiner sentiment | Improved | Refiners positioned for heavy sour feedstock optionality |

| Insurance and political-risk chatter | Up | Markets begin pricing “governance risk,” not only “oil risk” |

The key point is that the Donroe Doctrine behaves like a selective accelerant. It accelerates certain trades and timelines while leaving others almost untouched, at least until second-order effects arrive.

Oil Reality Check: Venezuela’s Barrels Are Not “Plug And Play”

Venezuela’s giant reserve figure is real, but reserves do not equal readily exportable supply. Much of the country’s crude is heavy or extra-heavy, and its production system has suffered from years of underinvestment, managerial turnover, and sanctions-related constraints. Bringing barrels back is an engineering project and a governance project at the same time.

Heavy crude also reshapes the map of winners. Many U.S. Gulf Coast refineries were built to process heavy sour grades efficiently. When heavy barrels are scarce, refiners pay up for substitutes and adjust their slates. When heavy barrels reappear, those refiners can gain margin advantages. This is why downstream players watch Venezuela with a different lens than upstream producers do.

At the same time, the “Venezuela is back” narrative has hard limits:

- New investment requires legal clarity on contracts, property rights, and export licensing.

- Production increases require stable electricity, secure fields, working ports, and functioning labor relations.

- Heavy crude often needs blending and specialized logistics, which can bottleneck quickly.

So the Donroe Doctrine creates a paradox. It can increase investor optimism about future production while simultaneously increasing near-term instability risk that reduces output. Markets will keep toggling between those poles until the transition proves it can deliver order.

Constraints Versus Catalysts For An Oil Rebound

| What Helps A Rebound | What Blocks A Rebound |

| Clear transition authority recognized by major buyers | Competing claims to legitimacy and contract authority |

| Predictable licensing and sanctions pathway | Sanctions ambiguity that scares off banks and insurers |

| Security for pipelines, ports, and power | Sabotage, strikes, or factional conflict |

| Capital commitments from credible operators | Political backlash against “resource-first” governance |

| Downstream demand for heavy sour grades | Logistics bottlenecks and diluent shortages |

Debt And CITGO: Where The Donroe Doctrine Meets Hard Money

If oil is the long game, debt is the immediate scoreboard. Venezuela’s defaulted bonds moved because intervention increased the perceived probability of a restructuring that investors can actually settle. Distressed markets trade on enforceability. A transition that can sign deals, lift constraints, and stabilize exports is a transition that can generate cash flow and negotiate terms.

CITGO sits at the center of that logic because it is a high-value Venezuelan-linked asset located in the United States, operating real refineries and infrastructure. Court processes around the PDV Holding ownership structure have given creditors a path to value, and the reported multi-billion-dollar bid level became a psychological anchor for recovery math.

Here is where the Donroe Doctrine adds a new layer. If Washington influences recognition and sanctions, it can also shape the practical pathway for settlement:

- Which Venezuelan authority is treated as a legitimate counterparty

- Whether new financing can enter the country without violating rules

- How quickly commercial flows can normalize

- Whether asset disputes become political bargaining chips

This is not a claim that debt outcomes are dictated from Washington. It is a claim that political control over licensing and recognition can raise or lower the friction costs of any deal. In distressed finance, friction is value. Reduce friction and recovery value rises. Increase friction and litigation wins.

A Simple Map Of Who Has Leverage In A Restructuring

| Stakeholder | Primary Leverage | What They Want |

| U.S. policy apparatus | Licensing, recognition, sanctions relief timing | Security outcomes, orderly transition, reputational control |

| Creditors | Legal claims, asset seizure pathways | Recovery value and enforceable settlement |

| Venezuelan interim authorities | Domestic legitimacy, control of institutions | Fiscal room, political survival, service restoration |

| Oil operators and service firms | Capital and technical capability | Contract stability, payment certainty, long-term access |

International Law Blowback: Why “Norm Risk” Becomes Market Risk

A major reason this story is bigger than Venezuela is the precedent. International institutions and many governments treat unilateral intervention as a violation of core principles of sovereignty. When those norms weaken, two market-relevant things happen.

First, countries hedge. They diversify trade partners, build alternative payment channels, stockpile strategic goods, and rewrite contracts to limit foreign leverage. That is not abstract morality. It is risk management, and it raises costs.

Second, investors begin to price “norm risk” into frontier and emerging markets. If regime change is perceived as a tool that can be deployed for strategic or resource reasons, then political-risk premiums expand beyond the immediate target. The Donroe Doctrine label intensifies that effect because it signals doctrine-like repeatability, not a one-off exception.

There is also an operational risk. Even a transition welcomed by parts of the population can trigger counter-mobilization, sabotage, or regional proxy dynamics. Markets often underprice these in the first week because they are hard to quantify. Then they reprice sharply after the first major incident. That is why the next phase matters more than the initial raid.

The Hemisphere’s Balancing Act: Security, Migration, And Political Contagion

Latin America’s response is likely to be mixed, and that mix itself creates uncertainty. Many leaders do not want Venezuela’s instability exporting crime and migration. Many also do not want to normalize a model where a powerful neighbor removes governments.

This tension produces “double-track diplomacy.” Public condemnation can coexist with quiet security coordination. The practical question is whether the transition reduces violence and restores basic services quickly. If it does, some governments will treat the episode as a grim success and move on. If it does not, the region will treat it as a warning, and political movements will weaponize it domestically.

Migration is the most immediate pressure point. A stable Venezuela could slow flows over time. A chaotic transition can spike them quickly. For the United States, that turns a foreign policy episode into a domestic political variable, which in turn pressures timelines and decisions on sanctions, aid, and security support.

If you want to understand what comes next, watch three indicators: border flows, fuel availability inside Venezuela, and the coherence of the transition authority. When those fail, everything else becomes harder.

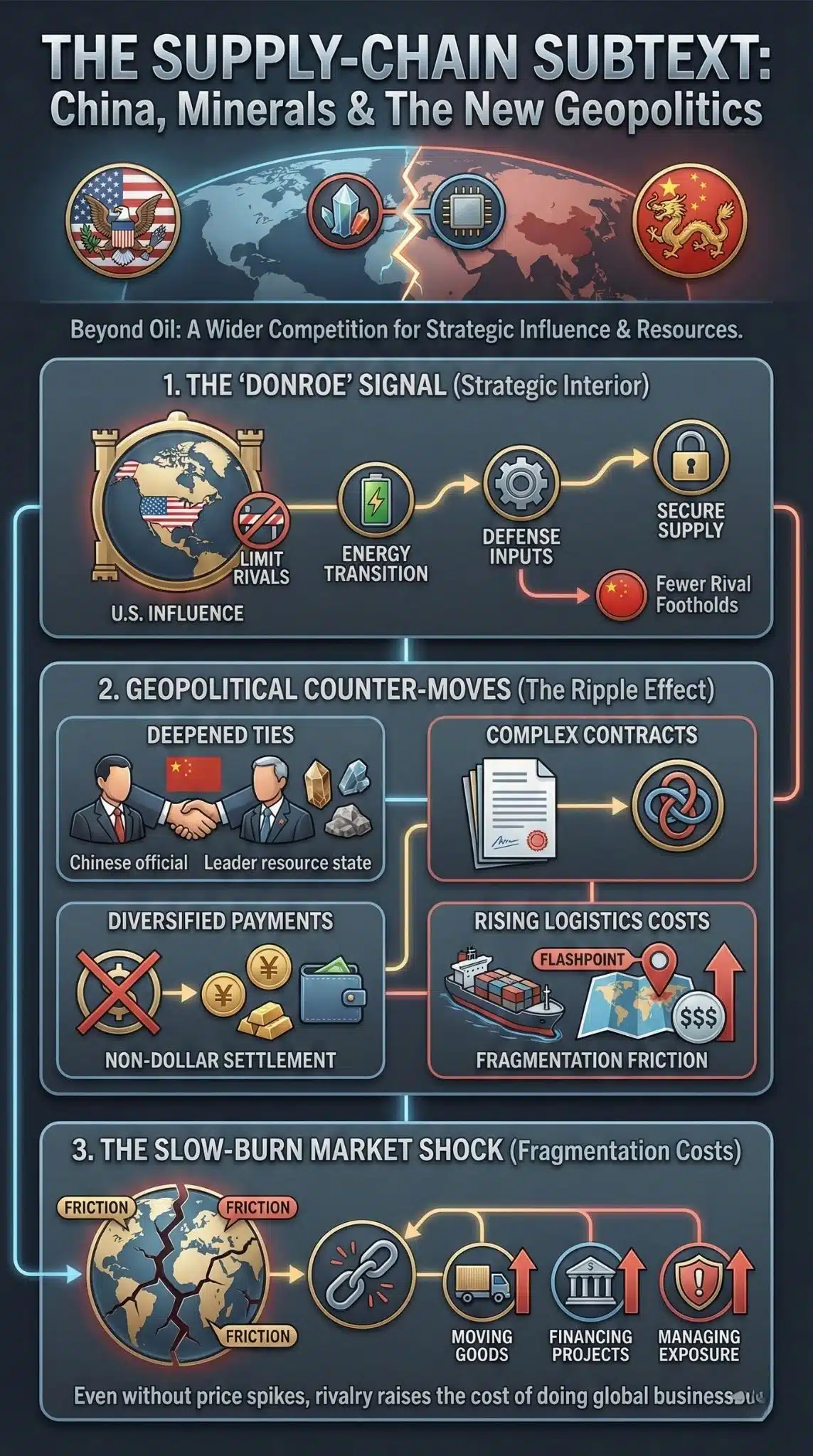

China, Minerals, And The Supply-Chain Subtext

Venezuela is also embedded in a wider competition over resources and influence. Oil is the headline, but strategic minerals and supply-chain positioning are the subtext. A doctrine that openly treats the hemisphere as a strategic interior signals that Washington wants fewer rival footholds near U.S. shores, especially in sectors tied to energy transition supply chains and defense-industrial inputs.

This matters because geopolitical rivalry tends to generate counter-moves:

- Rival powers deepen ties with other commodity states.

- Contract structures become more complex and politicized.

- Payment channels diversify away from simple dollar settlement in some cases.

- Insurance and shipping costs rise around perceived flashpoints.

Even if oil prices remain relatively calm, fragmentation can still raise the cost of moving goods, financing projects, and managing political exposure. That is a slow-burn market shock, and it is exactly the kind that doctrines create.

Winners And Losers: The Early Scorecard

| Potential Winner | Why | Potential Loser | Why |

| U.S. Gulf Coast refiners | More optionality if heavy sour supply normalizes | Competing heavy-oil exporters | Price and market-share pressure into the same refinery system |

| Distressed-debt funds | Higher recovery expectations under a workable transition | Venezuela’s near-term stability | Transition periods can trigger sabotage, strikes, and service collapse |

| Creditors with U.S.-based claims | Stronger enforcement pathways tied to U.S. assets | Regional diplomatic cohesion | Precedent fights can fracture hemispheric cooperation |

| Logistics and trading desks | Volatility and rerouting create opportunity | Sanctions-compliance exposed firms | Higher compliance costs and legal uncertainty |

What To Watch Next: The 2026 Milestones That Decide The Outcome

The Donroe Doctrine’s lasting impact will be determined by governance details, not by slogans. Here is a practical watchlist that investors and policymakers will track in 2026.

Governance And Legitimacy

If the transition authority is broad-based, time-bound, and tied to a credible election process, market optimism can persist and broaden into real investment plans. If it is vague or open-ended, the risk of insurgency and diplomatic isolation rises, and capital stays cautious.

Sanctions And Licensing Path

Sanctions relief is not a binary switch. It is a compliance ecosystem. Banks, insurers, and traders will not move at full speed without clarity on licenses, enforcement posture, and end-user rules. Expect a stepwise approach, and expect friction.

Oil System Stability

Watch whether fields operate without disruption, whether ports remain secure, and whether domestic fuel distribution improves. If domestic fuel shortages persist, the transition’s political legitimacy weakens fast, even if exports improve.

Debt And Asset Settlement

A credible path to restructuring can unlock medium-term recovery. A legitimacy dispute can freeze it and push everything back into court fights. The market’s early bond rally is a bet on coordination. Coordination is fragile.

Regional Spillovers

Border incidents, migration spikes, and proxy activity can force neighboring states into hard choices. Each hard choice feeds back into investor confidence.

A Scenario Grid For 2026

| Scenario | What It Looks Like | Market Implication |

| Managed Transition | Clear election timeline, basic services improve, security stabilizes | Debt recovery strengthens; investment planning begins |

| Resource-First Transition | Oil reopening prioritized, political roadmap unclear | Higher long-term risk premium; regional backlash risk rises |

| Fragmentation And Sabotage | Violence, strikes, infrastructure attacks | Oil and product volatility increases; investment freezes |

| Legal And Legitimacy Stalemate | Competing authorities, contested contracts, slow licensing | Restructuring delayed; volatility shifts to litigation and compliance |

Final Thoughts

This episode matters beyond Venezuela because it changes expectations about how power and markets interact. The 1990s and early 2000s taught investors to focus on globalization, trade integration, and technocratic policy. The 2020s and mid-2020s have been teaching the opposite lesson: geography, coercion, and resource access are back at the center.

The Donroe Doctrine is a label for that reality in the Western Hemisphere. It tells investors and governments that the U.S. is willing to fuse security logic with commodity logic. That fusion can stabilize a broken state if the transition is credible and locally legitimate. It can also create a cautionary precedent that drives hedging, fragmentation, and retaliation elsewhere.

The immediate market shock was quiet because the global oil market had slack and because investors could isolate the event into a handful of trades. The long-run shock could be louder because doctrines replicate. If this becomes a template, markets will start pricing doctrine risk into other resource-rich, institutionally weak states, especially those near strategic trade corridors.

In 2026, the most important question is not “will Venezuela pump more oil next month.” The question is “will the hemisphere accept a new rulebook, and will Venezuela’s transition prove that force can produce legitimacy.” Markets can live with volatility. They struggle with a world where the rules keep changing.