A “BlackRock Tokenized Housing Fund” isn’t just a flashy product idea. It’s a stress test for whether housing, the most politically sensitive asset in America, can be turned into fast-trading digital shares without breaking affordability, trust, or market stability.

Key Takeaways

- The biggest story is not the token. It is the infrastructure shift that could make housing exposures trade, settle, and post as collateral faster than today.

- “Tokenized housing” can mean many things: equity in rental portfolios, debt tied to mortgages, or digital share classes of existing real estate funds. Each has different risks.

- Housing is unlike Treasuries: its prices are local, its liquidity is slow, and its social role is explosive. Tokenization raises the odds of policy backlash.

- The real risk is a liquidity illusion, where something that trades quickly still depends on assets that underwrite slowly.

- The near-term path is institutional-first (qualified purchasers, private channels), not mass retail “own 0.01% of a home on your phone.”

- What comes next depends on regulation, secondary-market design, and whether tokenization is framed as “better plumbing” or “Wall Street buying homes.”

From BUIDL To Bricks: How Tokenization Reached Housing?

There is a reason tokenization keeps coming back in waves. Every market cycle produces the same complaint in different clothes: finance can move at internet speed, but the pipes under it still settle like it is the 1990s. Tokenization is the latest attempt to modernize those pipes by representing ownership as a digital record on a distributed ledger, letting transfers happen with fewer handoffs, cleaner audit trails, and potentially shorter settlement.

That is why the first serious institutional tokenization successes have clustered in instruments that already behave like cash. Tokenized Treasury and money-market-style products work because they sit on clean, standardized assets with frequent pricing, well-understood legal wrappers, and institutional-grade custodianship. They also solve an obvious problem: idle on-chain cash that wants yield without leaving the blockchain environment. If you can hold a token that behaves like a fund share and can be transferred peer-to-peer, you get yield plus operational flexibility.

Housing is the opposite end of that spectrum. It is heterogeneous, locally regulated, slow to transact, expensive to maintain, and emotionally loaded. That is exactly why a “tokenized housing fund” would be such a consequential leap. If tokenization can be made to work for housing exposures, it signals the rails are maturing. If it cannot, it exposes the limits of digitizing ownership when the underlying asset does not behave like a liquid security.

A critical clarification: as of early 2026, there is no widely documented, publicly branded BlackRock product officially launched under the name “Tokenized Housing Fund.” What exists instead is a set of powerful signals: BlackRock-backed tokenized cash products, industry moves to tokenize fund shares, and a policy environment increasingly obsessed with housing affordability and investor participation. The phrase “BlackRock Tokenized Housing Fund” therefore functions as a proxy question: what would it mean if the world’s largest asset manager applied the tokenization playbook to housing exposure?

Below is a simple timeline showing why this idea is emerging now, not five years ago.

| Period | What Changed In Markets | Why It Matters For Tokenized Housing |

| 2008–2012 | Housing crash, foreclosures, bulk purchases by investors | Institutional ownership narratives begin, and housing becomes politicized as finance’s “original sin.” |

| 2013–2019 | SFR industry professionalizes, REITs scale, property tech grows | Rental portfolios become more “fund-like,” making them easier to package into investable exposure. |

| 2020–2022 | Pandemic housing surge, affordability shock, investor activity peaks in some cycles | Public tolerance drops for anything that looks like financialization of housing. |

| 2023–2025 | Tokenized cash and fund-share initiatives expand; on-chain collateral use cases grow | Tokenization becomes less about crypto ideology and more about operational efficiency. |

| 2026 | Housing affordability stays high-stakes; political proposals target investor buying | Any housing tokenization attempt becomes inseparable from regulation and public trust. |

The “how we got here” is not a single announcement. It is convergence: tokenization is moving from experimental to institutional, while housing is moving from a household issue to a national political obsession. Put those together and you get a combustible product concept: a tokenized vehicle for housing exposure that could be framed either as democratization or as a new accelerant for financialization.

Why A BlackRock Tokenized Housing Fund Hits A Political Nerve?

Housing is not just an asset class. It is a social contract: stability, community, family formation, and the most common store of household wealth. That is why a tokenized housing product triggers immediate “why” questions that Treasuries do not.

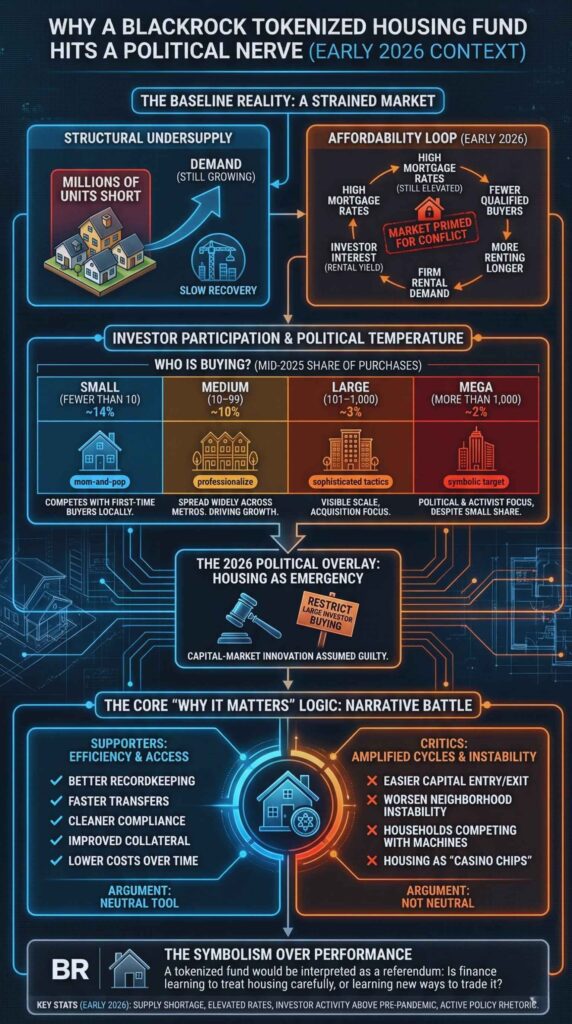

Start with the baseline reality: housing is still structurally undersupplied in the United States by millions of units, even after years of construction recovery. That means the market is primed for conflict. When supply is tight, every new source of demand becomes controversial, especially demand that can pay cash, move fast, and outbid households.

At the same time, the affordability story is stubborn. Mortgage rates in early 2026 are still high enough to keep many would-be buyers on the sidelines, and that creates a loop: fewer buyers can qualify, more people rent longer, rental demand stays firm, and investors see a reason to keep buying rental stock when returns pencil out. Any product that looks like it could channel additional capital into housing will be judged against that affordability backdrop.

Investor participation is where the political temperature rises. Market data in 2025 showed investors were a large share of single-family purchases, and the mix matters. “Investors” are not one group. They include small landlords, medium-scale operators, and mega portfolios. The public debate often centers on the biggest names, but in many markets the growth is driven by medium-sized investors who buy enough to influence neighborhoods yet are not “institutional” in the classic sense.

Here is a snapshot of what investor buying looked like in 2025, broken down by size categories reported in housing market research:

| Investor Type | Typical Portfolio Size | Share Of Purchases (Example Mid-2025) | Why The Politics Differ |

| Small | Fewer than 10 properties | ~14% | Often framed as “mom-and-pop,” but still competes with first-time buyers locally. |

| Medium | 10–99 properties | ~10% | Big enough to professionalize, small enough to spread widely across metros. |

| Large | 101–1,000 properties | ~3% | Visible scale, often uses sophisticated acquisition tactics. |

| Mega | More than 1,000 properties | ~2% | The symbolic target in politics and activism, even when national share is small. |

Now add the 2026 political overlay: proposals to restrict large investor buying of single-family homes have entered mainstream debate. Regardless of whether such proposals become law, the signal is clear. Housing is being treated as a political emergency, and capital-market innovation is increasingly assumed guilty until proven helpful.

This is the core “why it matters” logic: a tokenized housing fund would arrive at the exact moment public institutions are trying to decide whether housing should be treated more like shelter policy or more like an investable sector. Tokenization, fairly or not, is easily framed as turning homes into chips in a casino, because it implies faster trading and fractional participation. That framing can be politically devastating, even if the underlying exposure is economically similar to what already exists via REITs, mortgage-backed securities, homebuilder equities, and private real estate funds.

A useful neutrality check is to hold two ideas in mind at once:

- Supporters argue tokenization is mainly about efficiency. Better recordkeeping, faster transfers, cleaner compliance, and improved collateral management could reduce costs and broaden access over time.

- Critics argue efficiency is not neutral in housing. If you make it easier for capital to enter and exit, you may amplify cycles, worsen neighborhood instability, and increase the sense that households are competing with machines.

That is why this product concept is not just “a new fund.” It is a narrative battle over what housing is allowed to become in a financial system that keeps searching for yield and liquidity.

Key Statistics (Early 2026 context)

- U.S. housing supply remains undersupplied by millions of units relative to long-run demand.

- Mortgage rates remain elevated versus the pre-2022 era, sustaining lock-in effects and limiting resale inventory.

- Investor activity remains meaningfully above many pre-pandemic baselines, with the middle cohort of investors playing a larger role than headlines often imply.

- Policy rhetoric is actively targeting large investor participation in single-family homes.

If BlackRock ever put its name behind a tokenized housing vehicle, the fund’s performance would matter less than its symbolism. It would be interpreted as a referendum on whether the financial system is learning to treat housing carefully, or learning new ways to trade it.

Liquidity Promises Vs Housing Reality: The Financial Plumbing

Tokenization is often sold with a simple promise: liquidity. But that promise is easy to misunderstand.

A token can trade quickly. The underlying asset might not. Housing is slow, and it is slow for structural reasons: title processes, inspections, financing contingencies, local taxes, property condition, tenant rights, and the fact that each home is unique. No blockchain changes a roof repair or an eviction moratorium. This is where the risk of a liquidity illusion becomes central.

So what would a “tokenized housing fund” actually tokenize?

In practice, the most plausible structures are not tokenized deeds for individual houses. They are tokenized securities that reference housing economics. For example:

- Digital share classes of an existing real estate fund that owns rental portfolios.

- Tokens representing limited partnership interests in a private real estate vehicle.

- Tokens tied to debt exposures like mortgage credit or real estate lending funds.

- A feeder structure that routes eligible investors into a housing strategy, with token transfers recorded on-chain.

These approaches matter because they define the core risk: mismatch between redemption expectations and asset sale reality.

Here is a practical comparison of how a conventional housing exposure fund and a tokenized version could differ. The investment thesis may look similar, but the operating model can shift meaningfully.

| Feature | Conventional Real Estate Fund Exposure | Tokenized Fund Exposure (Potential) | The Real Tradeoff |

| Ownership Record | Transfer agent and fund administrator systems | Ledger-based record plus traditional admin in the background | Cleaner audit trails, but still needs conventional governance. |

| Settlement | Often T+1/T+2 or slower for private transfers | Potentially faster transfer finality | Faster transfers can increase trading and volatility around NAV. |

| Access | Brokerage, private placement channels, subscriptions | Wallet-based onboarding plus compliance gates | Onboarding can improve, but investor eligibility limits remain likely. |

| Liquidity | Periodic windows, limited secondary transfers | Wider secondary transfer possibilities | Risk rises if secondary price decouples from real asset value. |

| Collateral Use | Usually limited in traditional plumbing | Potentially easier to post as collateral | Collateralization can increase leverage and pro-cyclicality. |

The biggest forward-looking implication is collateral. Tokenized fund shares, especially if accepted by major platforms, can become financial building blocks. Once a share can move 24/7 and be pledged quickly, it may be used in repo-like transactions, margin arrangements, or structured yield products. That can deepen liquidity, but it can also create new failure modes.

Housing-linked collateral is particularly sensitive because real estate cycles already amplify leverage. If tokens tied to housing exposure become easy collateral, you can end up with layered leverage on top of an asset class that is slow to reprice and expensive to unwind. That is not a theoretical fear. It is how financial crises propagate: liquid wrappers on illiquid assets, combined with leverage and correlated behavior.

A neutral expert view would say: tokenization is not automatically destabilizing, but it increases the speed at which stress can travel. In housing, speed is dangerous because the social system around housing cannot adapt quickly. Renters, homeowners, city councils, and courts do not move at blockchain speed.

This is where the “BlackRock Tokenized Housing Fund” idea becomes revealing. The market does not actually need tokenized housing to create housing exposure. It already has it. The market is really asking for something else:

- faster settlement.

- easier collateral usage.

- better cross-platform interoperability.

- and perhaps lower distribution costs.

If that is the real goal, the question becomes: can you capture those plumbing benefits without importing speculative dynamics into a sector where backlash is immediate?

Rules, Rights, And Guardrails: Who Gets Protected?

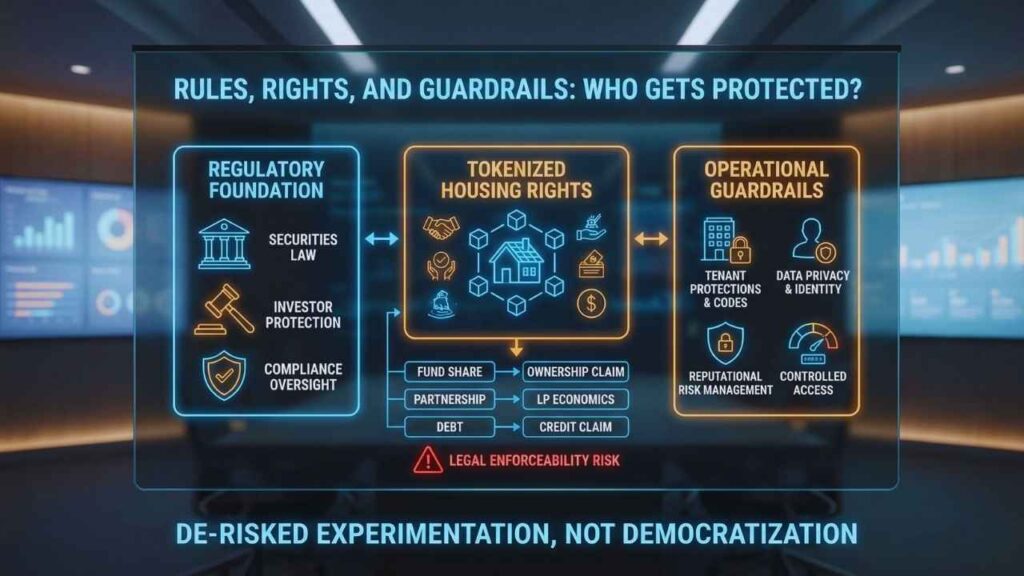

Tokenization does not escape regulation. It changes how compliance must be implemented.

A tokenized housing fund would still be a securities product in almost any plausible structure. That means investor protections remain in force: disclosures, suitability constraints, custody standards, valuation oversight, and restrictions on who can buy or trade depending on the wrapper. Regulatory caution is especially strong when the token is created by a third party instead of the original issuer, because that can introduce confusion about rights and legal enforceability.

In housing-linked products, rights clarity is everything. If an investor holds a token, what do they actually own? Cash flows? Voting rights? Redemption rights? A claim on a trust? Or just an IOU from an intermediary? Many retail-facing token projects fail not because the blockchain is broken, but because the legal claim is vague, or because enforcement depends on a fragile chain of intermediaries.

A practical way to keep this clear is to map token types to real-world rights.

| What The Token Represents | Typical Underlying Claim | Main Investor Risk | Regulatory Focus |

| Fund Share (Digital Share Class) | Ownership in a registered or private fund | Valuation and redemption rules, operational risk | Disclosure, custody, transfer restrictions, investor eligibility |

| Partnership Interest | Claim on LP economics | Governance opacity, limited liquidity | Private placement rules, suitability, reporting |

| Debt Instrument Linked To Housing | Claim on interest and principal | Credit risk, servicing complexity | Lending disclosures, securitization rules, risk retention considerations |

| Synthetic Exposure | Derivative-like payoff | Counterparty and model risk | Derivatives oversight, marketing restrictions, risk disclosures |

Now layer on the housing-specific guardrails that are not purely financial:

- Tenant protections and local housing codes still apply to properties owned by any fund vehicle.

- If tokenization increases trading frequency, governance over property decisions does not become “on-chain.” Someone still decides rent policy, renovations, and eviction strategy.

- Data privacy becomes more complex when ownership records and transfers intersect with wallet identity, onboarding providers, and cross-border platforms.

A major reputational risk for any large asset manager is that a product built for market efficiency is perceived as a mechanism for faster acquisition of homes, or for converting neighborhood housing stock into tradeable yield instruments. Even if the fund only targets multi-family or housing credit rather than single-family homes, the perception problem remains.

That is why, if such a product ever appeared, it would likely launch with tight constraints:

- eligible investors first, not broad retail.

- strong KYC and transfer restrictions.

- conservative redemption mechanics.

- robust third-party servicing and custody.

- and a communications strategy focused on efficiency, transparency, and risk controls.

In other words, the near-term play is not “democratization.” It is de-risked experimentation under controlled access. The irony is that this makes the product less revolutionary for everyday investors, at least initially.

But the infrastructure impact can still be profound. Once major managers normalize tokenized share classes, the baseline expectation for settlement and collateral capabilities shifts across the industry. Housing exposure may not become “meme tradable,” but the operational rails under real estate investing can still change.

What Happens Next For Tokenized Housing In 2026 And Beyond?

Forecasting here requires humility. The most honest outlook is scenario-based, because tokenized housing touches three uncertain variables at once: regulation, market adoption, and politics.

Still, a forward-looking analysis can identify likely milestones and pressure points.

The Institutional-First Scenario (Most Likely Near Term)

Tokenized housing exposure grows in private channels: feeder funds, tokenized LP interests, and digital share classes of housing credit strategies. The goal is not public trading. The goal is operational efficiency and collateral utility. In this world, “tokenized housing” mostly means easier movement of institutional capital and faster back-office processes, not widespread fractional home ownership.

The Policy-Backlash Scenario (Always Possible)

If housing affordability remains politically acute, policymakers could treat any tokenized housing product as a provocation, even if it does not meaningfully increase demand. Restrictions on investor buying, enhanced disclosure rules, or limits on certain acquisition strategies could become more common. Under this scenario, tokenization slows not because the tech fails, but because the social license collapses.

The Infrastructure Breakthrough Scenario (Medium-Term Upside)

Tokenized fund-share standards mature, settlement rails become interoperable across major custodians, and regulated secondary trading venues expand. In this world, tokenization becomes boring, which is exactly what you want. The main benefits show up in lower frictions, improved collateral management, and reduced operational costs. Housing exposure products improve at the margin, but the headline “tokenized housing” becomes less important than the pipes behind it.

The Speculation Spillover Scenario (Key Risk To Watch)

If tokenized housing exposures become widely used as collateral in leveraged strategies, risk can concentrate quickly. The danger is not that houses trade instantly. The danger is that the wrapper trades instantly while leverage builds on top of it. If a shock hits, forced selling can occur in the wrapper market even though the underlying property market cannot clear at the same speed.

Here are concrete milestones worth watching in 2026–2027, framed as “what comes next” rather than hype.

| Milestone To Watch | What Would Signal Progress | What Would Signal Trouble |

| Regulatory clarity on tokenized securities | Clear frameworks for issuance, custody, and trading venues | Conflicting guidance, enforcement-led rulemaking, or abrupt restrictions |

| Expansion of tokenized fund share infrastructure | More large managers offering digital share classes | Fragmented standards and interoperability failures |

| Housing policy targeting investor participation | Balanced measures that address supply and affordability | Broad bans that increase uncertainty and freeze capital |

| Secondary market design | Transparent pricing and controlled liquidity features | Thin liquidity, big discounts to NAV, and retail confusion |

| Collateral usage growth | Conservative haircuts and robust risk management | Excessive leverage and cascading margin calls |

So where does the “BlackRock Tokenized Housing Fund” idea land?

It matters less as a literal product name and more as a signal of the next frontier. BlackRock’s moves in tokenized cash and digital share classes suggest the firm, and the broader industry, are exploring how far tokenization can go when it is anchored in regulated fund structures. Housing is the highest-stakes test case because it sits at the intersection of finance, inequality, and politics.

A grounded prediction for 2026 if a BlackRock-linked tokenized housing exposure product emerges, it will likely be framed as a controlled, institutionally distributed vehicle that improves settlement and collateral processes, not as a retail-friendly home-fraction app. It will also likely avoid direct messaging that implies “we are tokenizing homes,” because that is the fastest path to backlash. The language will be about fund shares, infrastructure, and efficiency.

The real “why” is this tokenization is trying to turn financial ownership into software. Housing is where society draws lines about what should and should not become software. If the industry gets the design right, tokenized housing exposure could modernize real estate investing without destabilizing communities. If it gets the design wrong, the backlash will not just hit one fund. It could chill a broader wave of financial infrastructure innovation.