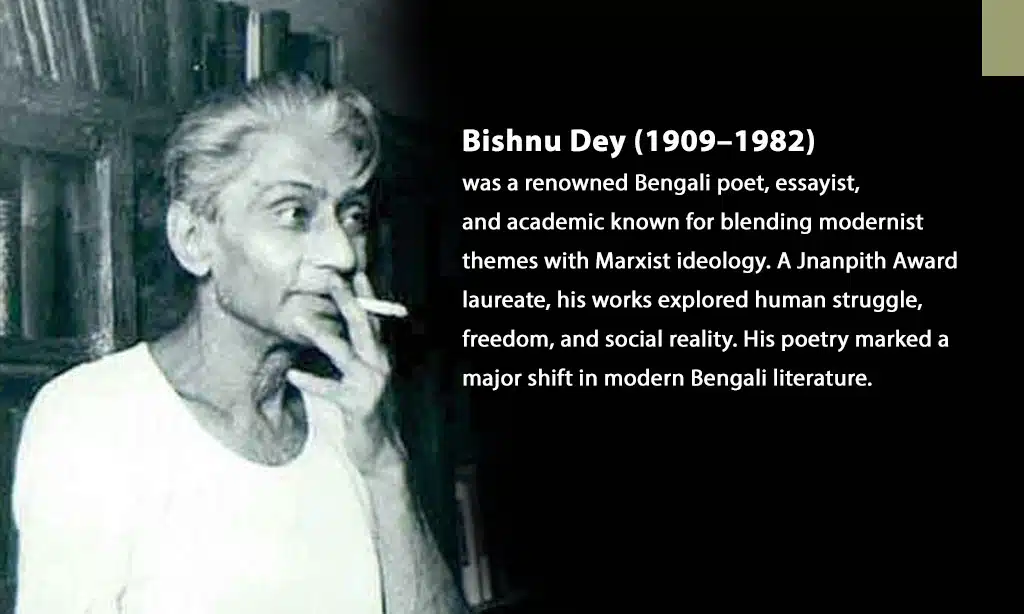

As we mark the forty-third anniversary of Bishnu Dey’s passing, it is hard not to feel how alive his voice still is in Bengali culture. Born in 1909 in Calcutta and gone from us since 3 December 1982, he stands at a rare intersection of roles. He was a fierce modernist poet, a Marxist intellectual, a patient classroom teacher, and a tireless critic of literature and art.

For readers in Bengal and beyond, remembering him today is not only an act of nostalgia. It is a way of taking stock of what modern Bengali literature tried to do in the twentieth century and what it still asks of us now.

This tribute looks at Bishnu Dey in three overlapping roles. The poet who reshaped Bengali modernism. The thinker who joined politics with aesthetics. The teacher who carried global and local traditions into the minds of young students.

Here is a multidimensional remembrance of Bishnu Dey on his death anniversary and a reflection on why his work still matters.

Bishnu Dey in His Time

Modern Bengali poetry between the two World Wars took shape in a period of economic hardship, anti-colonial struggle, and rising political ideals. In that restless landscape, a new group of poets moved away from the dominant Tagorean style. They experimented with language, imagery, and subject matter, often from a position of dissent.

Bishnu Dey is one of the central figures of this turn. He belongs to the Kallol generation, alongside Buddhadeb Basu, Jibanananda Das, Sudhindranath Dutta, and others, who were seen as voices of “New Poetry” in Bengali.

Some key points from his life place him clearly in that story

- Born in North Calcutta on 18 July 1909 to a middle-class family

- Educated at Mitra Institution and Sanskrit Collegiate School, then at Bangabasi College and St Paul’s College, where he studied English and encountered Western literature, music, and Marxist philosophy

- Early involvement with the Kallol circle of young poets

- Career as a teacher of English literature at Ripon College, Presidency College, Maulana Azad College, and Krishnanagar College

- Active in cultural politics and a founder member of the Anti-Fascist Writers and Artists Association in 1942

By the time of his major work “Smriti Satta Bhabishyat” (Memory, the Being, the Future), written between the mid-1950s and early 1960s, he had become widely recognized as one of the most demanding and significant voices in modern Bengali poetry. That book later brought him the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1965 and the Jnanpith Award in 1971, India’s highest literary honor.

The Poet: Difficult, Musical, Deeply Modern

Readers and critics often call Bishnu Dey a “difficult” poet. The tag is partly fair. His work is packed with layered imagery and references to history, science, world literature, and political struggles. The poems do not open themselves at a first casual reading.

But behind that difficulty lies a clear intention. Dey wanted poetry to match the complexity of modern life, not retreat from it. He drew on Marxist thought, on the fragmentation of the twentieth century, and on the techniques of modernist writers like T.S. Eliot, whom he admired and translated into Bengali.

Some features of his poetry stand out

- A strong urban sensibility, with Calcutta as a recurring presence

- Tension between memory, present struggle, and imagined future

- Use of scientific and historical images to talk about human fate

- A persistent concern with human dignity under pressure

Collections such as “Urvashi O Artemis,” “Chorabaali,” “Purbolekh,” “Sandwiper Chawr,” “Anwishta,” and “Naam Rekhechhi Komal Gandhar” trace his journey from early experiments to a more mature, layered voice.

“Smriti Satta Bhabishyat” marks a peak in that journey. Critics often describe it as a turning point in Bengali poetry, where time, being, and political history are woven into a single, demanding but rewarding tapestry.

On this death anniversary, returning to these books is one of the most direct ways to honor him. They remind us that modernism in Bengali was not an imported fashion. It was a way of thinking through colonialism, war, famine, and social change in the language of this region.

The Thinker: Marxist, Critic, Cultural Worker

To see Bishnu Dey only as a poet is to miss a large part of his contribution. He was also a critic of literature and art, a translator of world poetry, and a public intellectual grounded in Marxist ideas.

He believed that art could not be separated from history and class. At the same time, he resisted flat slogans or didactic writing. Dey’s Marxism pushed him to look closely at the forces shaping society, without giving up on aesthetic complexity.

His prose works show how wide his interests were

- “Ruchi O Pragati” and “Sahityer Bhabishyat” explore taste, progress, and the direction of literature.

- “The Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore” and “India and Modern Art” analyze how Indian artists responded to modernity.

- “The Art of Jamini Roy,” co-written with art historian John Irwin, examines a major painter who linked folk traditions with modern form.

He wrote on physics legend Satyendranath Bose, on aesthetics in “In The Sun and the Rain,” and on the place of African and Asian voices in global culture through his translations and essays.

In 1942, he helped found the Anti-Fascist Writers and Artists Association, which linked the fight against fascism with a broader commitment to progressive thought and cultural freedom.

Seen from today, this role of thinker and organizer feels as important as his poetry. At a time when literary and artistic circles often fragment into isolated groups, his example reminds us of a different model. He is not only a poet but also a person who edits, organizes, writes criticism, and engages in critical thinking about institutions and public life.

The Teacher: Classroom as Another Stage

For almost his entire adult life, Bishnu Dey taught English literature. He worked at Ripon College, Presidency College, Maulana Azad College, and Krishnanagar College across several decades.

Generations of students remember him as a demanding but generous teacher. The classroom, for him, was not separate from poetry. It was another stage on which questions of language, history, and ethics could be raised.

Some aspects of his teaching life deserve special notice

- He used English literature classes to introduce students to global modernism, while always linking back to Bengali writing

- He saw education as a way to build critical thinking and political awareness, not only to prepare for exams.

- He encouraged young writers to read widely, translate, and engage in debate.

Because he moved between institutions with very different student bodies, he also saw the unevenness of education in Bengal. That experience sharpened his sense of class and opportunity, which is visible in both his poetry and essays.

On this anniversary, many of his former students and their students, now teachers themselves, keep his memory alive when they approach the classroom as a place for open, curious minds rather than passive note-taking.

A Multi-Layered Legacy

Bishnu Dey received major awards in his lifetime. The Sahitya Akademi Award in 1965, the Jnanpith Award in 1971, the Nehru Smriti Award, and the Soviet Land Award for “Rushati Panchashati” all recognize his literary stature.

Yet awards are only one part of his legacy. The deeper parts are harder to measure but easier to feel.

He helped prove that Bengali poetry could be rigorously modern without losing its music. It could converse with European and global thought and still remain rooted in local realities. That Marxist commitment and aesthetic ambition could coexist inside the same mind without flattening each other.

He showed how a poet can also be

- A translator who opens windows to other traditions

- An art critic who takes painting and cinema seriously

- An educator who sees students as future shapers of culture

For younger readers today, some of his poems may still feel “difficult” at first contact. The references can be dense. The arguments do not always move in straight lines. But once you spend time with his work, a strong sense of human solidarity and ethical urgency shines through.

He is, finally, a poet of struggle, memory, and human fulfillment, who insists that even in dark times, the quest for dignity and meaning cannot be abandoned.

Why Bishnu Dey Still Matters Today

On the forty-third anniversary of his passing, why should a young reader, student, or writer care about Bishnu Dey

Because many of the tensions he worked through are still with us

- Rapid social and technological change

- Rising inequality and political polarisation

- Pressure on artistic freedom and critical thinking

- Confusion about how to connect local culture with global forces

His poetry does not offer easy answers. It does something harder. It teaches us how to think and feel inside these contradictions without giving in to despair or shallow optimism.

His essays on art and literature remain useful for anyone who wants to understand how modern Indian culture negotiated colonial influence, nationalism, and global modernism. His teaching life stands as a reminder that classrooms can still be spaces of resistance, curiosity, and care.

To read Bishnu Dey on his death anniversary is to engage with a demanding but generous mind. It is to accept his invitation to move beyond comfort and to see art as a serious way of knowing the world.

Here, then, is the simplest tribute we can offer today. Keep his books in circulation. Teach his poems and essays. Argue with him. Learn from him. And let his example of poet, thinker, and teacher continue to shape how we imagine the cultural life of Bengal and the wider world.

Frequently Asked Questions on Bishnu Dey

Here are the most frequently asked questions people have about Bishnu Dey.

Who was Bishnu Dey in simple terms

Bishnu Dey was a leading modern Bengali poet, born in 1909 and active through the mid-twentieth century. He wrote complex, intellectually rich poems that responded to colonialism, war, and social change. At the same time, he was a teacher of English literature, a Marxist thinker, a translator, and an art critic. He is often counted among the most important Bengali poets after Rabindranath Tagore.

Why is Bishnu Dey considered a modernist poet

He is called a modernist because he broke away from more traditional styles and took on the fractured, ambiguous feel of the twentieth century. His poems use dense imagery, shifting voices, and references to science, history, and world literature. This style, influenced in part by T.S. Eliot and by Marxist thought, marked a new direction in Bengali poetry that critics describe as “New Poetry.”

What are some of Bishnu Dey’s most important works?

Among his early and middle period collections are “Urvashi O Artemis,” “Chorabaali,” “Purbolekh,” “Sandwiper Chawr,” “Anwishta,” and “Naam Rekhechhi Komal Gandhar.” His landmark work is “Smriti Satta Bhabishyat,” which brought him both the Sahitya Akademi Award and the Jnanpith Award. In prose, he is known for books such as “The Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore,” “India and Modern Art,” “The Art of Jamini Roy,” and essay collections on literature and aesthetics.

How did Bishnu Dey influence later Bengali writers?

Later poets and critics inherited from him a sense that poetry could be both politically alert and formally ambitious. He helped normalize the idea that Bengali literature could converse with global modernism without losing its own identity. Many writers also followed his example as a critic and translator, seeing these roles as part of a wider literary duty rather than side activities. His teaching career shaped countless students who went on to become writers, teachers, and cultural workers themselves.

What is the best way for a new reader to start with Bishnu Dey?

A new reader can start with selected or collected poems where editors have already chosen accessible pieces across their career. It helps to read slowly, look up references, and accept that some poems will open only on a second or third reading. Pairing his poetry with short essays about him or by him, especially on literature and art, can provide context that makes the poems feel less intimidating and more rewarding.