Today marks the solemn death anniversary of Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin, the fearless engine room artificer whose sacrifice on the banks of the Rupsha River remains one of the most heartbreaking chapters of the Liberation War.

The air in December 1971 was thick with a mixture of gunpowder, hope, and an overwhelming anticipation of freedom. By the second week of December, the map of East Pakistan was changing rapidly. The occupation forces were retreating; the Allied Forces (Mitro Bahini) and the Mukti Bahini were tightening the noose around Dhaka. Victory wasn’t just a dream anymore; it was a certainty, visible on the horizon. Yet, history is often cruelest in the final moments before the dawn.

On the banks of the Rupsha River in Khulna, the tides still wash over the memory of a tragedy that occurred exactly 54 years ago today. Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin loved his ship more than his life and was martyred attempting to save the BNS Palash.

On this day, his death anniversary, we do not just remember a soldier; we remember a guardian who stood firm in the fire while the world around him burned.

The Boy from Noakhali: A Simple Village, A Quiet Dream

To understand the hero, one must first understand the man. Ruhul Amin was born in 1935 in the quiet village of Bagpanchra in Sonaimuri, Noakhali. Like many young men of that era from the riverine delta, he was drawn to the water. The rivers of Bangladesh breed a specific kind of resilience—a quiet toughness necessary to survive floods and storms.

In 1953, leaving behind his matriculation studies, he joined the Pakistan Navy as a junior mechanical engineer. It was a prestigious path, yet one fraught with the systemic discrimination that Bengalis faced in the armed forces of United Pakistan. For nearly two decades, Ruhul Amin served with distinction, rising to the rank of Engine Room Artificer Class-1. He wasn’t a political ideologue; he was a professional. He understood machines. He understood the rhythm of a ship’s engine, the smell of diesel, and the intense heat of the boiler room.

But by 1971, the professional had to become a patriot. Posted at the PNS Bakhtiar in Chittagong, he witnessed the cracks in the country widening. When the crackdown began in March and the genocide unfolded, the choice was no longer about career or duty to the state; it was about duty to the motherland. In April 1971, risking court-martial and death, he escaped the naval base. He didn’t run home to hide. He crossed the border into India, specifically to the Agartala sector, looking for a way to fight back.

Forging a Navy from Scratch: A Life Built in the Engine Room

The Bangladesh Liberation War is often visualized through the lens of guerrilla fighters in lungis carrying rifles through paddy fields. However, a crucial, often overlooked chapter is the birth of the Bangladesh Navy—Sector 10.

When Ruhul Amin joined the resistance, the “Navy” was barely a concept. There were no destroyers, no frigates, and no submarines. There were only passionate sailors who had defected and a desperate need to control the waterways of riverine Bangladesh.

India gifted two tugboats to the Mukti Bahini: the Padma and the Palash. These were not warships. They were civilian vessels intended for towing, slow and cumbersome. Converting them into fighting machines required ingenuity, and this is where Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin became indispensable.

He was assigned to the Palash. As the Engine Room Artificer, he was the ship’s doctor. He spent long, grueling hours in the belly of the ship, retrofitting the engines to handle the extra weight of armor plating and anti-aircraft guns. He knew that in a firefight, speed and maneuverability would be their only defense. He treated the Palash not as a piece of metal, but as a living entity.

By September 1971, thanks to the tireless work of technicians like Amin, the Bangladesh Navy was ready to launch offensive operations. They weren’t just a nuisance to the Pakistani Navy; they were a legitimate threat, mining ports and cutting off supply lines.

The Final Voyage: When a Sailor Becomes a Freedom Fighter

As December arrived, the war entered its endgame. The Allied Forces decided to launch a decisive blow to capture the Mongla seaport and liberate the industrial city of Khulna. It was a high-stakes mission.

On December 6, the fleet set sail from Haldia, India. It was a small but proud formation: the Indian gunboat INS Panvel leading the charge, followed by the Mukti Bahini’s BNS Padma and BNS Palash.

The mood on board was electric. They successfully entered the Passur River at Hiron Point. On December 9, they captured the Mongla port with surprisingly little resistance—the Pakistani forces had fled. The path to Khulna seemed open. The sailors of the Palash, including Ruhul Amin, must have felt the rush of imminent victory. They were sailing home, liberators of their own waters.

The Tragedy at Rupsha

The morning of December 10, 1971, dawned with a deceptively clear sky. The convoy moved up the Rupsha River, approaching the Khulna Shipyard. They were deep in enemy territory, yet the greatest danger would not come from the banks but from the sky above.

Around noon, three fighter jets appeared overhead. The crew of the Palash cheered, waving their hands. They recognized the silhouette of the Gnats—these were Indian Air Force planes, their allies. They believed they were receiving air cover for the final push into Khulna.

On the deck, the crew felt safe. They had spread large yellow cloths across the rooftops of the Padma and Palash—the agreed-upon signal to let the Indian Air Force know, “We are friends.” We are Mukti Bahini.’ But from thousands of feet in the air, amidst the haze of the river delta, that signal was lost. The pilots saw only gunboats moving toward a Pakistani stronghold. In a tragic twist of fate, the very allies they were cheering for began to dive for the kill.

The jets dived. The first bombs hit the Padma. Then, they turned their sights on the Palash. The cheering on the deck turned to screaming. The ship shuddered violently as it was strafed. Explosions rocked the vessel. Smoke began to billow from the engine room—Ruhul Amin’s domain.

The Captain’s Order and the Engineer’s Choice

The Commander of the Palash realized the futility of the situation. They were taking heavy fire from their own allies. He gave the order to abandon ship to save the lives of his crew. Sailors began jumping into the river, desperate to escape the floating inferno.

But Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin did not jump. In the hierarchy of naval warfare, the captain commands the ship, but the chief artificer knows the ship. Amin knew that the Palash was one of only two fighting ships the new nation of Bangladesh possessed. If she sank, the Navy would be crippled before it could truly be born.

While others ran for the rails, Ruhul Amin ran back into the heat. The engine room was a death trap. The air would have been searing hot, filled with choking black smoke and the smell of burning oil. Yet, he stayed. He grabbed fire extinguishers, trying frantically to put out the flames. He was shouting orders to the remaining crew, ignoring his own safety, driven by a singular, obsessive thought: “I must keep the engine running. I must save the ship.”

A shell struck the engine room directly. The explosion threw him back. His body was battered, burned, and broken. The ship was lost. Only then, with the Palash listing and consumed by fire, did he accept the inevitable.

The Betrayal on the Shore

Wounded and exhausted, Ruhul Amin leaped into the Rupsha River. The water must have stung his burns, but the survival instinct kicked in. He swam through the debris and the oil slicks, making his way toward the eastern bank.

He was a strong man, a survivor. He made it to the shore. He pulled himself up onto the mud, gasping for air, likely believing the worst was over. He had survived the airstrike; he had survived the fire. But the tragedy of Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin is that he did not die in the heat of battle against a foreign army. He died at the hands of his own countrymen, who had turned traitor.

Waiting on the bank was a group of Razakars—local collaborators who were supporting the Pakistani army. They had watched the bombing. They saw the Freedom Fighter emerge from the water, defenseless and injured. There was no mercy. In a display of brutality that stains the history of the war, they attacked him with bayonets. On the muddy banks of the Rupsha, within sight of the burning ship he tried so hard to save, Ruhul Amin was killed.

It was December 10. Khulna would be liberated just days later. He was so close to the finish line.

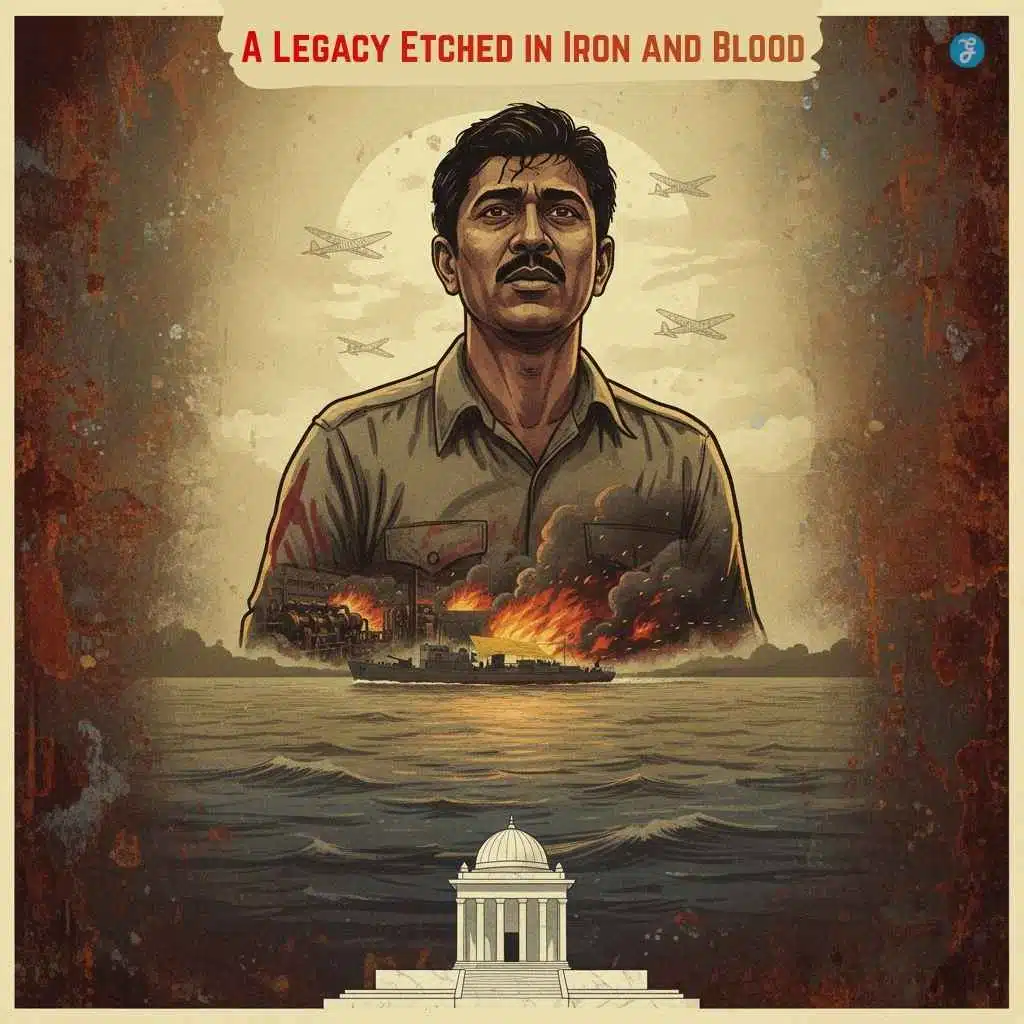

A Legacy Etched in Iron and Blood

His body was left on the riverbank, uncared for, until local villagers recovered it. They buried him near the incident spot, a quiet grave for a thunderous spirit.

After the war, the newly formed Bangladesh recognized the magnitude of his sacrifice. He was posthumously awarded the Bir Shreshtho, the highest gallantry award. But titles alone cannot capture the essence of his heroism.

Most soldiers fight to save their lives or defeat the enemy. Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin fought to save a machine—because he understood that for a poor, war-torn nation, that machine represented sovereignty. He knew that freedom would need a navy to protect it, and he was willing to trade his life to ensure that navy survived.

Today, if you visit Khulna, you can pay your respects at his mausoleum. It stands serene and peaceful, a stark contrast to the violence of 1971. The Bangladesh Navy has named a warship BNS Shaheed Ruhul Amin in his honor, ensuring that his name continues to sail the waters he died to protect.

A Hero, But Also a Husband and Father

It’s easy to talk about medals and missions and forget the human being behind them. Ruhul Amin was not just an engine room artificer or a name in bold print; he was also a husband and the father of five children. When he chose to join the Liberation War, he knew the risk he was taking—not only for himself but for the future of his family.

Years later, reports about his family say that they are “doing fine” and that some of his sons-in-law have built respectable careers, including one in the Bangladesh Navy. That small detail is powerful: the force that once took him away now also carries forward his legacy through another generation.

Imagine the emotional weight carried by his children. They did not grow up with a father who picked them up from school or sat with them over homework. They grew up with a portrait, a name, and a nation that salutes when it hears that name.

The Honour of “Bir Shreshtho”

After independence, the Government of Bangladesh carefully evaluated the stories of countless fighters whose bravery had changed the course of the war. Among them, seven were given the highest gallantry title: Bir Shreshtho – “The Most Valiant Hero.”

Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin was one of them.

The title itself is not just an award; it is a national promise that their names will never fade. Bir Shreshtho heroes are not merely “famous freedom fighters” – they represent the absolute peak of sacrifice: all of them were martyred in the line of duty.

Why Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin Still Matters Today

More than five decades later, why should a new generation care about an engine room artificer who died on a river they may never have seen?

Because his story answers questions we still struggle with:

What does real patriotism look like?

It’s not noise; it’s responsibility. Ruhul Amin didn’t post slogans or shout at rallies. He mastered his craft, did his duty, and when his country called, he put that skill at her service – with his life as collateral.

What does integrity mean?

Integrity is staying at your station when everything around you is burning. In modern life, our “engine rooms” might be offices, hospitals, classrooms, or homes. His choice reminds us that quiet, unseen work can be deeply heroic.

How do we deal with confusion and tragedy?

The attack on Padma and Palash was reportedly a tragic misidentification in the fog of war. Even then, Ruhul Amin did not waste time on blame or panic; he focused on saving the ship and protecting his comrades. That mindset—solve the problem in front of you, protect the people near you—is timeless.

In an era dominated by self-promotion and quick success, the life of Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin is a counter-narrative. He teaches us that excellence in a humble role can be just as noble as leadership on a grand stage.

Final Words: A Tribute and a Promise

As we light candles or bow our heads today, let us remember that the freedom of Bangladesh was bought at a high price. It was paid for by men like Ruhul Amin, who did not seek glory, who did not flee when the odds were impossible, and who stayed at their post when the sky itself turned against them.

He was the guardian of the engine room. He was the soul of the first fleet. And today, 54 years later, he remains an eternal flame in the heart of a grateful nation. As long as the Bangladeshi flag flies over this land and rivers like Rupsha continue to flow, his name deserves to be spoken with respect and love.

Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin, your sacrifice is not forgotten. You simply chose, again and again, to do what was right—until the very end. On this martyrdom day, we bow our heads and whisper:

“Salam to you, Bir Shreshtho Ruhul Amin. May we prove ourselves worthy of the freedom you died for.”