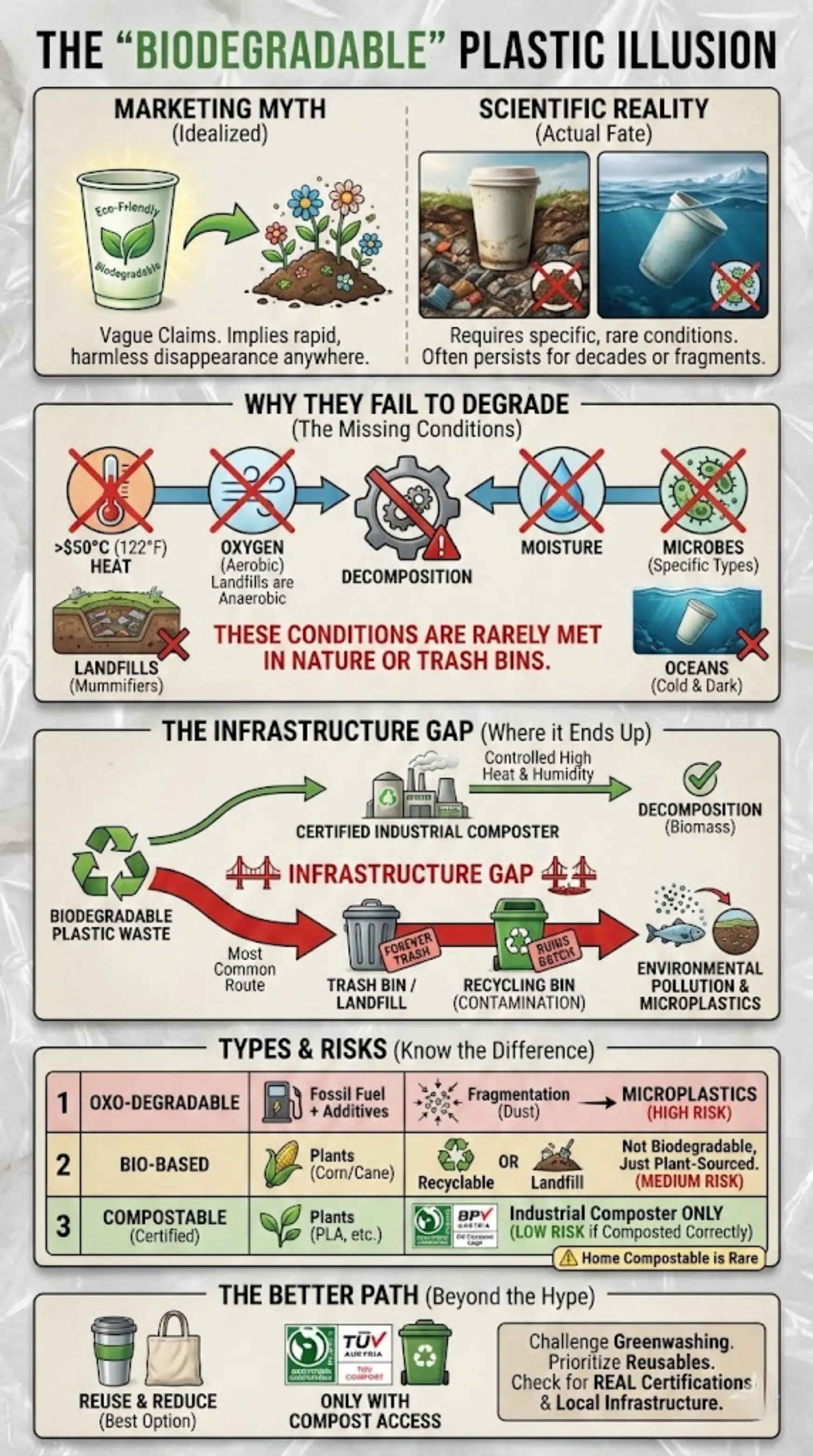

Walk down any supermarket aisle, and you will see them: distinct green labels proclaiming packaging to be “biodegradable,” “eco-friendly,” or “plant-based.” It feels like the responsible choice. You pay a little extra, assuming that once you toss that wrapper in the trash, it will harmlessly dissolve back into the earth like a fallen leaf.

The reality? That wrapper might outlive you.

The term “biodegradable” has become the centerpiece of modern biodegradable plastics greenwashing. While consumers are desperate for plastic pollution solutions, brands are capitalizing on confusion, marketing products that sound sustainable but often behave just like conventional plastic in the real world. This article investigates the gap between marketing claims and scientific reality, exposing the problems with biodegradable plastics and helping you navigate the murky waters of sustainable packaging.

What Does “Biodegradable Plastic” Actually Mean?

To understand the deception, we must first understand the definition. The word “biodegradable” is often used interchangeably with “compostable” or “eco-friendly” by marketers, but scientifically, they mean very different things.

Scientific Definition vs Marketing Definition

Scientifically, biodegradation is a chemical process where microorganisms (bacteria and fungi) convert materials into natural elements: water, carbon dioxide, and biomass. However, the crucial missing factor in marketing claims is time.

- Scientific Reality: Everything is eventually biodegradable. Even standard plastic will degrade over hundreds of years. A scientific claim of biodegradability is meaningless without a specific timeframe and set of conditions.

- Marketing Myth: Brands imply that “biodegradable” means the item will vanish in weeks or months, regardless of where you throw it. This vague usage is the core of the biodegradable plastics truth controversy.

How Long Does Biodegradation Really Take?

There is no universal timer for biodegradation. An apple core might decompose in two weeks on a forest floor, but take decades in a landfill.

- Industrial Conditions: In a high-heat, controlled facility, truly biodegradable bioplastics might break down in 90–180 days.

- Natural Environments: In the ocean or a roadside ditch, that same plastic might persist for decades.

Without strict parameters, a label saying “biodegradable” promises nothing more than eventual disintegration—potentially taking centuries.

Why “Biodegradable” Plastics Often Do Not Degrade

If you buy a biodegradable coffee cup and toss it in a general trash bin, you aren’t helping the environment. In fact, you might be adding to the problem. Here is why are biodegradable plastics really biodegradable in practice.

The Conditions Required for Decomposition

Plastic does not just disappear; it needs specific triggers to break its molecular bonds. Most biodegradable plastics require:

- High Temperatures: Often above $50^\circ\text{C}$ ($122^\circ\text{F}$).

- Oxygen: Essential for aerobic bacteria to work.

- Moisture: To facilitate microbial activity.

- Microbes: Specific populations of bacteria.

Landfills and oceans fail these conditions. Modern landfills are designed to be “mummifiers.” They are tightly compacted and sealed to prevent oxygen flow (anaerobic). In this environment, even organic matter like lettuce can last for 25 years. A “biodegradable” fork has almost no chance of decomposing there.

Industrial Composting vs Real-World Disposal

There is a massive infrastructure gap. Most “biodegradable” plastics are actually “industrial compostable.” They only break down in specialized facilities that maintain high heat and humidity.

- The Problem: Most cities do not have access to industrial composting facilities.

- The Result: Consumers unknowingly throw these plastics into recycling bins (where they contaminate the batch) or trash bins (where they are sent to landfills to sit forever).

Note: If your town doesn’t collect compost, your “green” plastic is likely just expensive trash.

Greenwashing Explained: How Plastic Claims Mislead Consumers

Greenwashing plastics examples are everywhere. Companies know that sustainability sells, so they exploit the lack of regulation to boost sales without changing their environmental footprint.

Common Greenwashing Tactics Used by Brands

- Vague Eco Labels: Terms like “Eco-Safe,” “Earth Friendly,” or “Green” have no legal definition.

- Partial Truths: Claiming a bottle is “made from plants” (Bio-based) without mentioning it isn’t biodegradable.

- Unverified Certifications: Using fake seal-of-approval logos that look official but are created by the company’s marketing department.

- The “Omnipresent” Green: Coloring packaging green or using kraft paper textures to signal “nature,” even if the product is lined with non-recyclable plastic.

Why “Biodegradable” Sounds More Sustainable Than It Is

This is purely psychological. We associate biodegradation with nature’s cycle—death and rebirth. When we see “biodegradable,” our guilt about single-use consumption vanishes because we imagine the waste disappearing harmlessly. Brands exploit this trust to sell single-use items, distracting us from the better solution: reuse.

Types of “Biodegradable” Plastics You Should Know

Not all eco-plastics are created equal. Understanding the terminology is your best defense against greenwashing.

Oxo-Degradable Plastics

Verdict: Avoid at all costs.

These are conventional plastics (like polyethylene) mixed with metal additives that cause the plastic to shatter into dust when exposed to UV light or heat.

- Fragmentation vs Biodegradation: They do not return to nature; they just turn into invisible microplastics faster.

- Microplastic Risk: These fragments persist in the soil and ocean, entering the food chain. Many countries (including the EU) have banned oxo-degradables due to this risk.

Bio-Based Plastics

Verdict: Misleading.

“Bio-based” refers to the beginning of the plastic’s life, not the end.

- Plant-Based $\neq$ Biodegradable: You can make PET (the plastic in water bottles) out of sugarcane instead of oil. It is chemically identical to oil-based plastic. It is not biodegradable; it is recyclable. Do not confuse the source with the disposal method.

Compostable Plastics

Verdict: Good, but conditional.

True compostable plastics (like PLA – Polylactic Acid) break down into non-toxic biomass.

- Industrial vs Home Compostable: Most are only industrial compostable. Very few carry the “Home Compostable” certification, meaning they will not break down in your backyard pile.

| Type | Source | End of Life | Risk Level |

| Oxo-degradable | Fossil Fuel + Additives | Microplastics | High |

| Bio-based | Plants (Corn/Cane) | Recyclable or Landfill | Medium |

| Compostable | Plants | Industrial Composter | Low (if disposed correctly) |

Environmental Impact: Are Biodegradable Plastics Helping or Harming?

When we look at the biodegradable plastic environmental impact, the picture is complex. While the intent is good, the outcome often creates new pollution streams.

Microplastics and Long-Term Pollution

Because “biodegradable” plastics often end up in the ocean or roadside (environments they weren’t designed for), they fragment rather than dissolve. A biodegradable bag floating in the cold ocean behaves much like a standard plastic bag: it can choke marine life or break down into microplastics that act as toxic sponges for pollutants.

Carbon Footprint and Resource Use

Bio-plastics rely on agriculture. Growing corn or sugarcane for packaging requires:

- Land Use: Converting forests or food-cropland into plastic-cropland.

- Water & Fertilizers: Intensive agriculture contributes to eutrophication (algae blooms) and water scarcity.

- Energy: The process of converting plants to plastic is energy-intensive. In some Life-Cycle Assessments (LCA), bio-plastics have a higher carbon footprint than recycled fossil-fuel plastics.

Regulations, Certifications, and Labeling Loopholes

If a product claims to be biodegradable, who verifies it?

Common Certifications Explained

To trust a claim, look for specific standards, not adjectives.

- BPI (Biodegradable Products Institute): A rigorous standard for industrial compostability in North America.

- Ok Compost Home (TUV Austria): Verifies that the item will degrade in lower-temperature backyard compost piles.

- ASTM D6400 / EN 13432: These are the technical standards ensuring a product breaks down within a set time (usually 90–180 days) in industrial conditions without leaving toxic residue.

Why Regulation Still Falls Short

Enforcement is the weak link. In many regions, brands can slap “Biodegradable” on a label with little consequence. Even when certified, if the local municipality lacks the collection infrastructure (green bins), the certification is theoretically true but practically useless.

Better Alternatives to “Biodegradable” Plastics

We cannot simply swap one disposable material for another and expect to solve the waste crisis.

Reusable and Reduction-Based Solutions

The most sustainable packaging is the one that doesn’t exist.

- Reuse-First Hierarchy: A steel water bottle used for 5 years beats 2,000 biodegradable cups.

- Refill Systems: Stores offering bulk bins for grains, soaps, and detergents eliminate packaging entirely.

Truly Sustainable Packaging Options

If packaging is necessary, look for:

- Paper/Cardboard: High recycling rates and naturally biodegradable.

- Aluminum/Glass: Infinitely recyclable materials.

- Mushroom/Algae Packaging: Emerging tech that is truly home compostable and low-impact.

How Consumers Can Avoid Falling for Greenwashing

You have the power to demand better. Here is how to shop smarter.

Questions to Ask Before Buying

- “Where does this go?” If the label says biodegradable but you have no compost bin, treat it as trash.

- “Is it certified?” Look for the BPI or TUV Austria logos. No logo = No trust.

- “Is it oxo-degradable?” If you see “degradable” (without the bio-), it’s likely microplastic dust in the making.

How to Read Sustainability Claims Critically

- Red Flags: Terms like “Bioplastic” (vague), “Earth-safe,” or green-colored leaves without text.

- Transparency Signals: QR codes linking to impact reports, clear instructions on disposal (e.g., “Industrial Compost Only”), and specific material names (e.g., “100% PLA”).

Final Thoughts: Moving Beyond the “Magic Vanishing Act”

The allure of biodegradable plastic is undeniable. It promises a world where our convenience culture doesn’t carry a heavy environmental price tag—a world where we can consume, discard, and let nature handle the rest. But as we have explored, this promise is largely an illusion.

While true compostable materials (like fungi-based packaging) hold incredible potential for the future, the current market is flooded with misleading claims and half-solutions. “Biodegradable” has become a buzzword that often excuses single-use habits rather than challenging them.

The uncomfortable truth is that we cannot shop our way out of the plastic crisis. Swapping a disposable plastic fork for a disposable bio-plastic fork is a lateral move, not a solution. The real answer lies in a systemic shift:

- For Brands: Moving from “less bad” packaging to truly circular systems (refill/reuse).

- For Governments: Enforcing strict definitions to banish vague marketing terms.

- For Consumers: Prioritizing reduction over degradation.

By all means, choose certified compostable products when disposables are necessary. But remember that the most eco-friendly product is the one you don’t throw away at all.