Scientists at Durham University in the UK are leading the charge in developing a revolutionary camera designed to scan distant planets for signs of alien life, marking a pivotal step in humanity’s quest to answer one of the universe’s biggest questions. This cutting-edge imaging technology, part of NASA’s ambitious Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) mission, promises to peer into the atmospheres of Earth-like exoplanets, hunting for chemical clues that could indicate biological activity.

The Technology Behind the Search

At the heart of this innovation is a high-resolution camera engineered to overcome the glare of stars, which often drowns out the faint signals from orbiting rocky planets. The device incorporates a coronagraph—a sophisticated light-blocking instrument—that shields the camera from stellar brightness, allowing for the first detailed views of these elusive worlds. This setup will enable measurements of a planet’s mass and detailed atmospheric analysis, focusing on biosignatures like oxygen, methane, or other molecules that suggest life.

Durham University’s Professor Richard Massey described the project as building the “Hubble Space Telescope of the 21st Century,” emphasizing its potential not just for astrobiology but for broader cosmic discoveries. The camera’s precision stems from collaborative UK expertise, blending advanced optics and sensor technology to detect subtle chemical imprints from light-years away. Early prototypes are already undergoing feasibility studies, with the full system integrating photonic components for enhanced sensitivity.

NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory: A Game-Changer

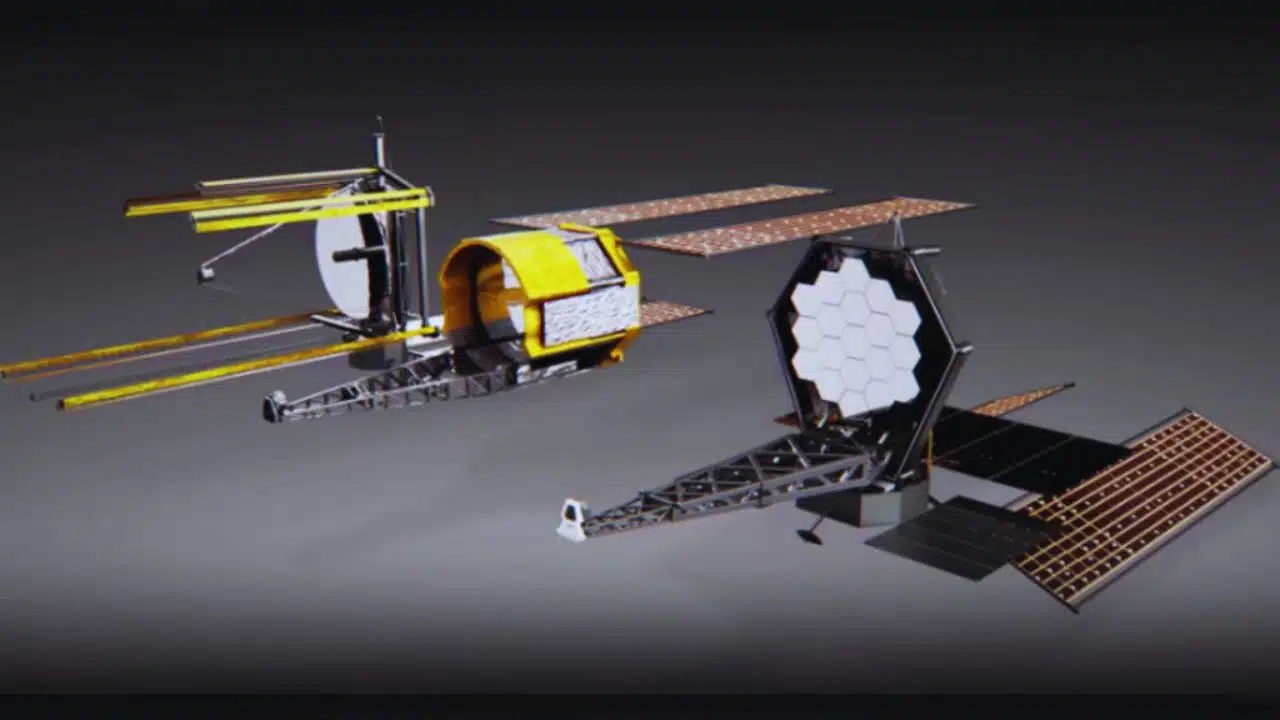

The HWO, slated for launch in the early 2040s, represents NASA’s next flagship telescope after the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), specifically tailored for habitable exoplanet exploration. Unlike previous observatories that indirectly infer planetary atmospheres through starlight transit, HWO will directly image dozens of promising worlds, analyzing reflected starlight for life indicators. This direct approach could reveal Earth twins—rocky planets in habitable zones with potential oceans or vegetation—far beyond our solar system.

The mission builds on recent JWST successes, such as detecting sulfur dioxide in exoplanet atmospheres, but HWO’s larger scale and targeted design will amplify these capabilities. Scientists anticipate it could survey up to 25 Earth-sized planets, prioritizing those around nearby stars like Proxima Centauri or in the TRAPPIST-1 system, where conditions might mirror our own. Beyond life detection, HWO will track asteroid impacts, probe black holes, and probe dark matter, expanding its scientific reach.

Challenges in Spotting Alien Biosignatures

Detecting life on exoplanets is no small feat; rocky worlds hug their stars closely, making them nearly invisible against the overwhelming stellar glare. Traditional telescopes struggle with this contrast, often requiring indirect methods like transmission spectroscopy, where planetary atmospheres absorb specific light wavelengths during transits. The new camera addresses this by combining coronagraphy with hyperspectral imaging, capturing data across infrared bands to identify molecular vibrations linked to organics or water.

Yet, false positives loom large—non-biological processes can mimic biosignatures, as seen in recent JWST observations of K2-18b, where dimethyl sulfide (DMS) signals faded under scrutiny. To counter this, the Durham team is incorporating machine learning for data analysis, training algorithms to distinguish biological from abiotic origins, such as chiral amino acids produced only by life. Lab simulations and computational models are refining these techniques, ensuring the camera’s outputs are reliable amid cosmic noise.

The UK Collaboration and Global Implications

This camera isn’t a solo endeavor; Durham joins forces with University College London, the University of Portsmouth, RAL Space, and the UK Astronomy Technology Centre, under UK Space Agency funding. A parallel effort at the University of Leicester explores complementary imagers, fostering competition and innovation. This UK-led hardware could position Britain as a key player in NASA’s HWO, potentially influencing future missions like the European Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), set for 2030.

Globally, the project ties into a surge in astrobiology tech, from neuromorphic cameras mimicking the human eye for faster imaging to compact life-detection chips weighing under a kilogram—ideal for probes to Enceladus or Europa. As Massey noted, such tools could “solve the mystery of our place in the universe,” blending astronomy with the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). If successful, this camera might deliver humanity’s first glimpse of alien ecosystems, reshaping our understanding of life in the cosmos.

In an era of rapid space exploration, this development underscores the accelerating pace of discovery. While the 2040s launch feels distant, the groundwork laid today could soon confirm we’re not alone—or redefine the boundaries of possibility.