Biodegradable electronics sound like science fiction, but the concept is becoming increasingly real. Imagine a sensor that tracks soil moisture for a growing season and then safely breaks down. Or a medical implant that monitors healing for a few weeks and then dissolves without surgery. Or packaging labels that communicate freshness and then disappear rather than adding to landfill waste. These are not just futuristic ideas. They are the kinds of use cases driving a fast-growing field sometimes called transient electronics.

Still, biodegradable electronics are not the same as “eco-friendly gadgets.” They are a specific class of devices designed to function for a defined period and then break down through biological, chemical, or environmental processes. The science is complex because electronics demand stability while they operate, but biodegradation requires controlled breakdown. The core challenge is building circuits that perform reliably long enough, then degrade safely, predictably, and with minimal harm.

This cluster guide explains the science behind vanishing circuit boards, what materials make biodegradation possible, how real devices are designed, where the field is already useful, and what limitations must be solved before biodegradable electronics can scale.

Why E-Waste Is The Problem Biodegradable Electronics Are Trying To Solve

Electronic waste is growing because devices are replaced faster than they are recovered. Many electronics contain mixed materials that are hard to separate and recycle. Some end up in informal recycling streams, creating health and pollution risks. Even when recycling exists, collection rates can be low, and recovery can be inefficient.

Biodegradable electronics target a specific part of the e-waste problem: short-life electronics that do not need to last for years.

Examples include:

-

Disposable medical sensors and single-use diagnostic patches

-

Temporary environmental monitoring systems

-

Agricultural sensors used for one season

-

Logistics and packaging sensors used for tracking and freshness

-

Temporary event and infrastructure monitoring devices

If these devices could vanish safely, the waste burden would drop. But the goal is not to replace durable electronics like smartphones with dissolving versions. The goal is to reduce waste from temporary electronics that are difficult to collect and recycle.

What Biodegradable Electronics Actually Are

Biodegradable electronics are designed to degrade after use. The device’s components are made from materials that can break down into less harmful substances through natural processes such as hydrolysis, microbial activity, or environmental exposure.

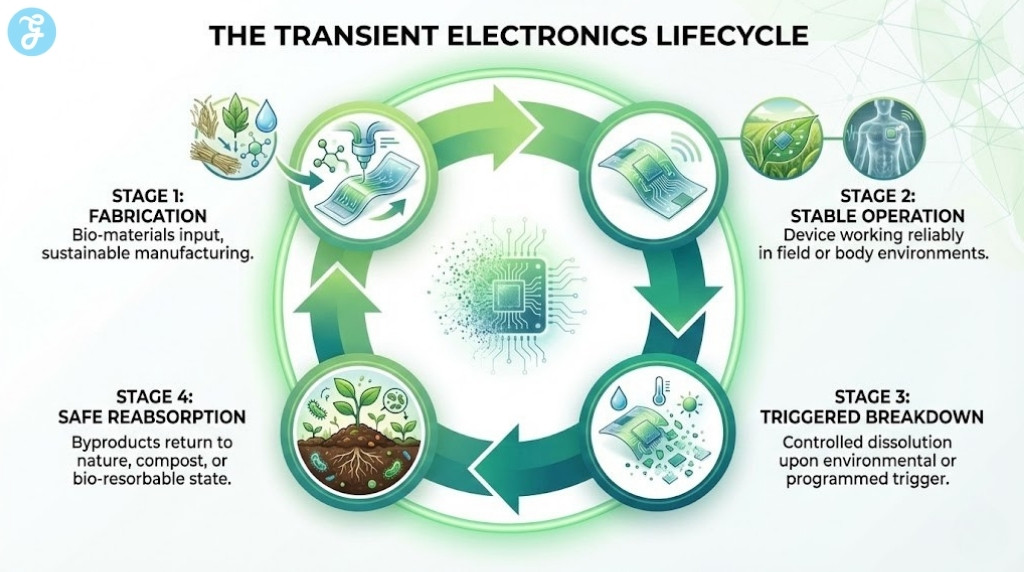

The key point is that these devices are engineered for two phases:

-

A stable operating phase where the device works reliably

-

A controlled degradation phase where the device breaks down predictably

This is why many researchers use terms like transient electronics. The electronics are temporary by design.

A Simple Definition Table

| Term | What It Means | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable electronics | Devices that break down via biological processes | Reduces long-term waste |

| Transient electronics | Devices designed to disappear after a set time | Enables temporary use cases |

| Dissolvable electronics | Often used for medical applications | Avoids removal surgeries |

| Compostable electronics | Devices designed for compost-like breakdown | Complex and still emerging |

Not every “bio-based” electronic is biodegradable. Some use plant-based plastics but still persist for a long time. True biodegradability requires material systems that degrade under realistic conditions.

How Circuit Boards “Vanish”: The Core Science

Traditional circuit boards are designed to resist heat, moisture, and corrosion. Biodegradable electronics need a different strategy. They must resist breakdown during use, but then degrade when triggered.

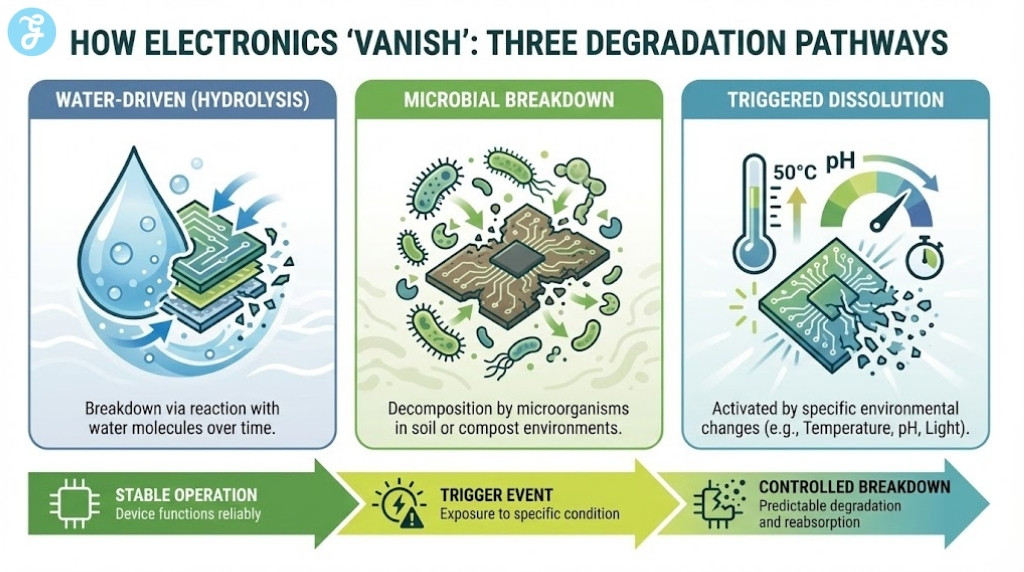

There are three common degradation pathways:

-

Water-driven breakdown through hydrolysis

-

Microbial breakdown through biodegradation of substrates

-

Triggered breakdown through changes in temperature, pH, or exposure

Engineers often control degradation by selecting materials and designing protective layers that delay exposure until the device’s job is done.

Degradation Pathways Table

| Pathway | What Triggers It | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Water exposure over time | Medical implants, sensors |

| Microbial breakdown | Soil microbes, compost conditions | Agriculture, environment |

| Triggered dissolution | pH, temperature, light | Specialized controlled systems |

The challenge is predictability. Real environments vary. Soil moisture changes, body chemistry differs, temperature fluctuates. So biodegradable electronics must be designed with robust timing controls.

The Key Building Blocks Of Biodegradable Electronics

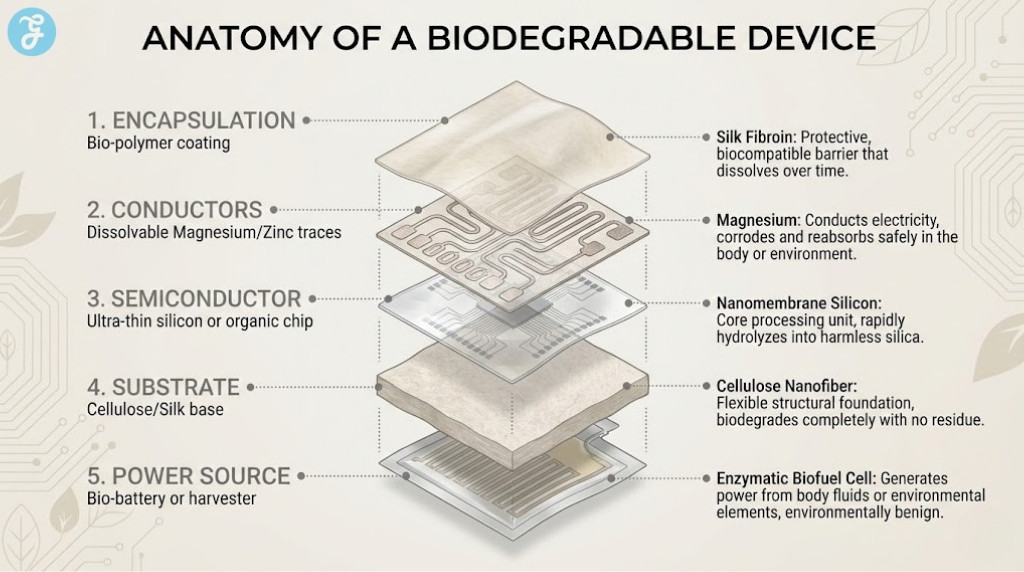

Electronics include multiple layers and components. A “vanishing circuit board” is not one material. It is a system of materials that must work together.

The main building blocks include:

-

Substrate: the base layer that holds the circuit

-

Conductors: pathways that carry electrical signals

-

Semiconductors: components that process signals

-

Dielectrics and insulators: materials that control current flow

-

Encapsulation layers: protective coatings that delay breakdown

-

Power sources: batteries or energy harvesters

Each component must either biodegrade or be minimal enough that it does not create meaningful waste. Power sources are one of the hardest problems.

Biodegradable Substrates: Replacing Traditional Circuit Boards

A circuit board substrate is the skeleton of electronics. Traditional boards use fiberglass-reinforced epoxy materials that do not biodegrade easily. Biodegradable electronics use alternative substrates that can degrade under specific conditions.

Common substrate candidates include:

-

Cellulose-based materials

-

Silk fibroin in biomedical systems

-

Polylactic acid and other bio-based polymers

-

Starch-based composites

-

Paper-like substrates for low-power circuits

Substrate choice affects strength, heat tolerance, and moisture sensitivity. Many biodegradable substrates perform best in low-power, short-duration devices.

Substrate Comparison Table

| Substrate Type | Strength | Biodegradation Potential | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose and paper | Medium | High in many conditions | Packaging and sensors |

| Silk-based | Medium | High in biomedical environments | Temporary implants |

| PLA-like polymers | Medium | Variable, depends on conditions | Consumer and industrial sensors |

| Starch composites | Lower | High in suitable environments | Short-life monitoring |

“Biodegradable” does not always mean “breaks down everywhere.” Some materials degrade well in industrial compost conditions but slowly in landfills. This matters for real-world impact.

Conductors: The Problem With Metals

Conductors are critical because circuits need pathways for electricity. Many conductors are metals like copper, gold, and silver. These do not biodegrade the same way polymers do.

Biodegradable electronics often use:

-

Ultra-thin metal traces that dissolve or corrode harmlessly in small amounts

-

Conductive polymers in limited applications

-

Carbon-based conductors for low-power circuits

-

Magnesium and zinc in transient systems, especially biomedical devices

The goal is to minimize persistent materials. Some devices are designed so metallic traces dissolve through controlled corrosion, but this must be done safely.

Conductor Options Table

| Conductor Type | Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Thin metal traces | Reliable conductivity | Not biodegradable, relies on dissolution |

| Magnesium or zinc | Dissolvable in certain environments | Limited durability and performance |

| Conductive polymers | Potential biodegradability | Lower conductivity and stability |

| Carbon-based | Useful for sensors | Not ideal for all circuit needs |

Conductors remain a major barrier for making fully biodegradable devices at scale.

Semiconductors: Can Chips Be Biodegradable

Semiconductors are harder. Traditional silicon chips are stable, durable, and not biodegradable in the common sense. Biodegradable electronics research often focuses on small, simple devices rather than fully chip-driven systems.

Some approaches include:

-

Ultra-thin silicon that dissolves in specific biomedical environments

-

Organic semiconductors that can degrade more easily

-

Minimal computing designs that reduce semiconductor complexity

-

Hybrid devices that use small persistent chips but biodegradable substrates

In many near-term products, biodegradability may be partial. The substrate and packaging may degrade, while a small chip remains to be recovered or kept minimal.

This raises an important point. Biodegradable electronics may reduce waste even when not fully biodegradable, if the non-degradable component is very small and recovery is realistic.

Encapsulation: The Layer That Controls Timing

Encapsulation is one of the most critical design elements. It is the protective coating that prevents moisture and oxygen from damaging the device too soon. In biodegradable electronics, encapsulation also controls when degradation begins.

Encapsulation strategies include:

-

Thin bio-based coatings that degrade slowly

-

Layered barriers that delay water exposure

-

Trigger-based coatings that dissolve under specific conditions

This layer is what allows a device to be stable for weeks or months, then break down afterward.

Encapsulation Timing Table

| Encapsulation Strategy | What It Does | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Slow-degrading coating | Gradual delay of moisture | Environmental sensors |

| Multi-layer barriers | Predictable timing control | Higher reliability needs |

| Triggered coatings | Dissolve under conditions | Biomedical and specialty |

Encapsulation is also where “greenwashing risk” exists. A device may be “biodegradable” in theory, but if it uses a highly persistent protective coating, real biodegradation may not happen.

Power Sources: The Hardest Part Of Vanishing Electronics

Power is the biggest challenge. Traditional batteries contain metals and electrolytes that can be hazardous or persistent. A truly biodegradable device needs a power system that either degrades safely or avoids batteries altogether.

Emerging strategies include:

-

Biodegradable batteries designed for controlled dissolution

-

Small energy harvesting systems such as solar, thermal, or vibration

-

Inductive power for short-range devices

-

Ultra-low-power designs that minimize energy needs

In many cases, the most realistic pathway is designing devices that need very little power and can use minimal or safer battery chemistry.

Power Options Table

| Power Option | Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable battery | Fully transient system goal | Chemistry and safety challenges |

| Energy harvesting | No battery waste | Limited power and conditions |

| Inductive power | No onboard battery | Requires external system |

| Ultra-low-power design | Extends life with tiny power | Limits device capability |

Until power systems improve, biodegradable electronics will remain strongest in low-power sensing and temporary applications.

Real-World Use Cases That Make Biodegradable Electronics Worth It

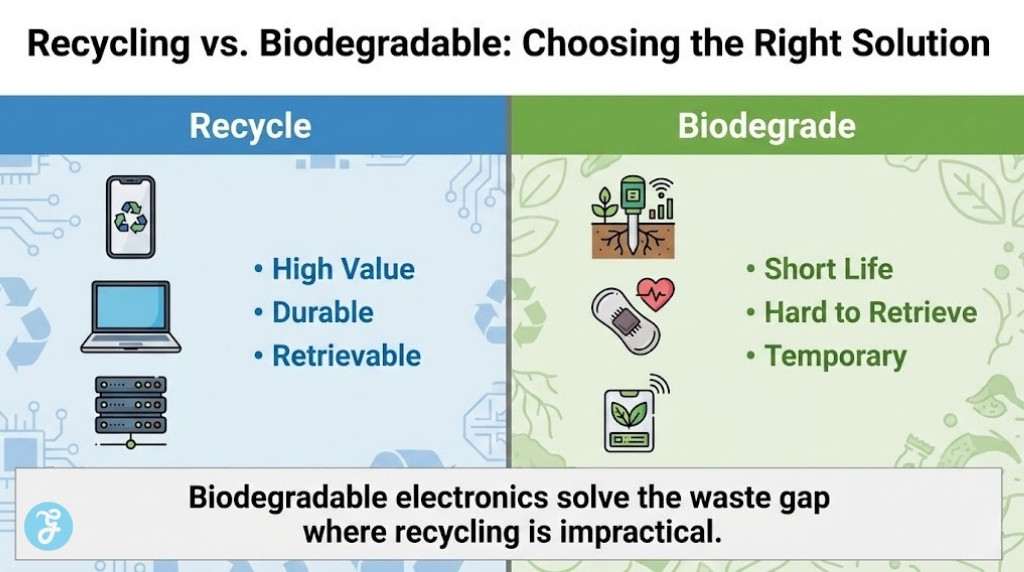

The best applications are those where device retrieval is costly or unrealistic. If you can easily collect and recycle devices, conventional circular strategies may be better. But if retrieval is impossible, vanishing electronics can reduce long-term harm.

High-fit use cases include:

-

Soil sensors left across large farms

-

Ocean and river monitoring devices

-

Temporary infrastructure sensors in hard-to-reach locations

-

Biomedical implants that should not require removal

-

Event monitoring systems for temporary installations

These are exactly the types of electronics that can become waste if they are not collected.

The Limitations: Why Biodegradable Electronics Are Not Everywhere Yet

Biodegradable electronics face multiple barriers.

Performance Constraints

Biodegradable materials often cannot match the heat tolerance, durability, and conductivity of conventional materials. That limits performance, especially for high-compute devices.

Predictability And Standards

Real-world degradation timing is difficult to guarantee. Different environments break materials down at different rates. Standards for “biodegradable electronics” are still evolving.

Safety And Toxicity

Materials must not release harmful substances when they degrade. This includes metal ions, coatings, and battery components.

Cost And Manufacturing Compatibility

Electronics manufacturing is optimized for traditional materials. New materials may require new processes, which can be expensive.

A Limitations Table

| Challenge | Why It’s Hard | What Progress Looks Like |

|---|---|---|

| Materials performance | Tradeoff with biodegradability | Stronger bio-polymers and composites |

| Timing control | Environments vary widely | Reliable encapsulation systems |

| Safe breakdown | Risk of harmful byproducts | Verified toxicity testing and standards |

| Scalability | Manufacturing is optimized for old materials | Compatible processes and supply chains |

Biodegradable electronics are not a replacement for repair, reuse, and recycling. They are a complement for situations where retrieval is unrealistic.

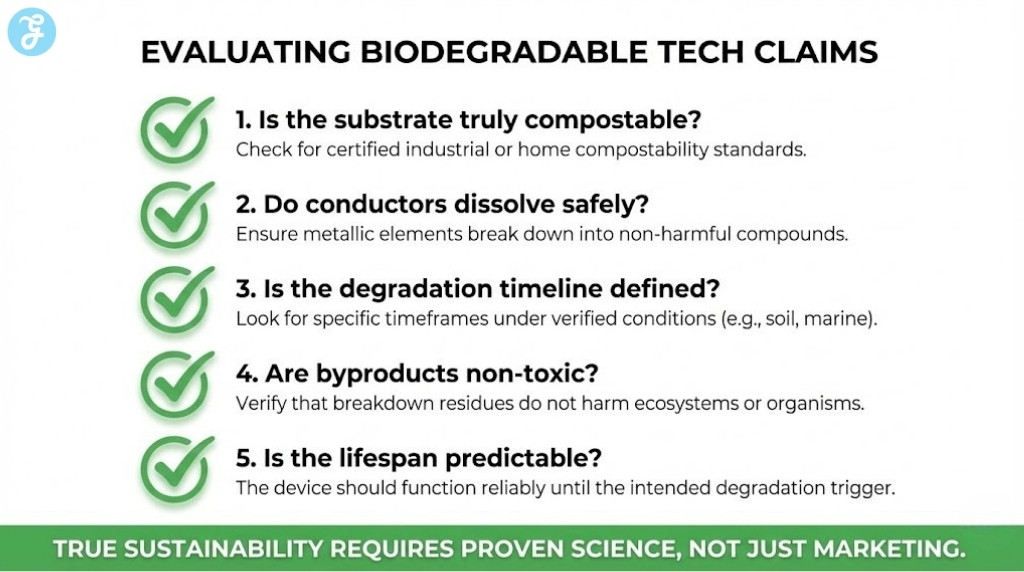

How To Judge A Biodegradable Electronics Claim

As the field grows, marketing will grow too. A good evaluation framework helps.

The Practical Claim Checklist

-

What components are biodegradable and what components remain?

-

Under what conditions does biodegradation occur?

-

How long does the device take to break down?

-

What byproducts are produced, and are they safe?

-

Is the device meant to be retrieved, or to vanish?

-

Is the claim supported by transparent testing?

Claim Clarity Table

| Claim Type | Better Interpretation | Risky Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| “Biodegradable” | Clear conditions and testing | Vague and undefined |

| “Compostable” | Industrial compost with standards | Home compost implied without proof |

| “Eco-friendly” | Measurable reduction in waste | Pure marketing |

| “Transient” | Designed lifetime and dissolution plan | Unpredictable breakdown |

The most credible products will explain timing, conditions, and safety.

How Biodegradable Electronics Fit The Green Tech Revolution

Biodegradable electronics are part of the broader shift from linear waste to designed circularity. Not every device can be collected and recycled. Some will always be lost in the environment or embedded in systems where retrieval is impractical. For those cases, making electronics that disappear safely could reduce long-term pollution.

This innovation also shows a larger trend in eco-innovation: building materials and systems that consider end-of-life from the beginning, not as an afterthought.

Biodegradable electronics push engineers to ask a different question. Not only, “Can we build it?” but also, “What happens after it’s done?”

Testing And Standards: How “Biodegradable” Gets Proven

Biodegradable electronics will not scale without shared standards. Today, many claims depend on lab conditions that may not match real environments. Soil chemistry, moisture, temperature, and microbial activity vary widely. Even a device that breaks down quickly in a controlled setup may degrade slowly in a dry field or a cold coastal zone.

To make the category trustworthy, the industry needs clearer testing norms that answer practical questions:

-

Under what conditions does the device degrade?

-

How long does the breakdown take?

-

What byproducts are produced during degradation?

-

What percentage of the device fully disappears versus remaining as residue?

A useful standard system would separate claims by environment, because biodegradation is not one universal outcome.

Standards Clarity Table

| Claim Label | Conditions That Should Be Stated | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Soil-biodegradable | Soil type, moisture range, temperature | Agriculture and land sensors |

| Marine-degradable | Salinity, currents, temperature | Ocean and river monitoring |

| Biomedical-dissolvable | pH range, fluid exposure, timeframe | Implants and medical sensors |

| Industrial-compostable | Compost temperature and process | Packaging electronics |

Without these qualifiers, “biodegradable electronics” risks becoming a vague marketing term instead of a technical category.

Designing For Controlled Lifetimes: The Engineering Trick

The hardest part of biodegradable electronics is not making something that degrades. It is making something that degrades on schedule. A practical device needs a predictable operating window. Too short and it fails before the mission is done. Too long and it becomes waste like any other device.

Engineers typically control lifetime through layered design choices:

-

Encapsulation thickness and composition

-

Placement of moisture-sensitive components

-

Barrier layers that slow water diffusion

-

Material blends that degrade at different rates

-

Mechanical structure that collapses after key layers weaken

This is similar to how some medicines are designed to release slowly, but applied to physical electronics.

Lifetime Control Table

| Control Method | How It Works | Best Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-layer encapsulation | Water reaches circuits gradually | Long-duration sensing |

| Trigger-based coatings | Coating dissolves at a target pH/condition | Biomedical systems |

| Weak-link design | A specific layer breaks first, disabling the system | Short-use tracking |

| Material gradient | Different layers degrade at different speeds | Predictable phase-out |

A strong transient device is one that is stable by design and degradable by design, not stable by luck.

Hybrid Approaches: When Partial Biodegradability Is Still A Win

In many real products, full biodegradability is not yet realistic. Chips, certain conductors, and power systems can be difficult to replace with biodegradable equivalents. But partial biodegradability can still reduce e-waste if it eliminates most of the device mass and makes the remaining parts easier to recover.

Hybrid strategies often look like this:

-

A biodegradable substrate and casing

-

Minimal metal traces designed to dissolve or corrode safely

-

A tiny “core” module that can be recovered or is small enough to reduce impact

-

A design that separates components during breakdown for easier collection

This matters because many waste problems are driven by scale. If millions of devices are deployed and retrieval is unrealistic, even a 70–90% reduction in persistent material can be meaningful.

Hybrid Strategy Table

| Approach | What Degrades | What Remains | Why It Helps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable body | Substrate, casing, coatings | Small electronics core | Reduces bulk waste |

| Dissolvable traces | Metal pathways dissolve | Sensors or chip core | Cuts long-term residue |

| Recoverable module | Outer structure degrades | Retrievable sealed module | Enables partial circularity |

This hybrid thinking keeps biodegradable electronics practical while materials science catches up.

Where Biodegradable Electronics Compete Best Against Recycling

Recycling is still essential for most electronics. But biodegradable electronics become the better option when collection is unlikely or too expensive. The strongest use cases are those where devices are distributed widely, embedded in environments, or used temporarily at scale.

High-fit examples include:

-

Farm sensor networks spread across large land areas

-

Temporary disaster-response monitoring systems

-

Ocean or wetland sensors where retrieval is dangerous

-

One-time medical monitoring systems used in high volume

-

Short-life supply chain and cold-chain sensors

In these cases, the “collect and recycle” model often fails in practice. That is where vanishing electronics can create a real sustainability advantage.

Use-Case Fit Table

| Scenario | Recycling Feasibility | Biodegradable Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Smartphones and laptops | High, collection possible | Low, durability is better |

| Seasonal farm sensors | Low, retrieval is costly | High, avoids scattered waste |

| Biomedical implants | Low, removal is invasive | High, avoids second surgery |

| Temporary event sensors | Medium, often forgotten | Medium, reduces leftover waste |

| Ocean monitoring | Very low, retrieval hard | High, prevents marine debris |

The point is not to replace recycling. It is to solve the gaps where recycling cannot realistically happen.

Safety And Environmental Risk: What Must Be Proven

For biodegradable electronics to be truly sustainable, degradation must be safe. That includes preventing harmful byproducts, especially from metals and power systems. A device that “disappears” but releases toxic residues is not a sustainability solution.

Safety evaluation should include:

-

Byproduct analysis during degradation

-

Toxicity testing for soil and water exposure

-

Bioaccumulation risk assessment for metals

-

Battery chemistry safety validation

-

Real-world trials in target environments

This is where credibility will be built. The best products will not just claim biodegradability. They will show tested outcomes and clearly defined conditions.

The Verdict?

Biodegradable electronics and transient circuit boards are emerging technologies designed for a world where e-waste is a growing burden. The science involves designing materials and structures that remain stable during use and then degrade predictably afterward. Substrates, conductors, semiconductors, encapsulation layers, and power sources all must be rethought.

The most realistic near-term applications are temporary sensors, agriculture, environmental monitoring, logistics, and biomedical devices. Power systems, conductor choices, and predictable degradation remain major challenges. As standards and materials improve, biodegradable electronics can become a meaningful tool in the sustainability toolkit, especially where collection is unrealistic.

Biodegradable electronics are not about replacing smartphones with dissolving gadgets. They are about making temporary electronics less permanent as waste.