Golden Globes 2026 put recycled couture back in the spotlight as stars leaned on vintage, archives, and reworked gowns to project taste and responsibility ahead of awards season. It matters now because fashion’s emissions are rising while new laws and resale markets push the industry toward circularity.

Key Takeaways

- “Recycled couture” has evolved into a red carpet shorthand for archive pulls, vintage couture, reworked heritage pieces, rentals, and highly crafted looks designed to last beyond one appearance.

- The Golden Globes 2026 rewarded classic glamour and “craft narratives,” including widely reported build times like 323 hours for Selena Gomez’s Chanel and 400-plus hours for Amanda Seyfried’s Versace.

- The sustainability case is getting harder to ignore as industry trackers link rising emissions to overproduction and heavy reliance on virgin polyester.

- Policy is turning circularity from a moral choice into a cost and compliance issue, especially through extended producer responsibility rules and fast-fashion restrictions.

- The next phase will revolve around measurement and proof: clearer disclosure, stronger standards, and infrastructure that makes reuse and textile-to-textile recycling scalable.

How Recycled Couture Moved From Statement To Strategy?

Red carpet sustainability used to be a niche storyline. A celebrity might wear a gown made from recycled materials, a stylist might mention ethical sourcing, and then the awards cycle would move on. The message lived in captions and interviews, not in the dominant visual language of glamour.

That began to change when climate messaging stopped being optional culture and started becoming mainstream politics and business risk. Fashion’s role became easier to explain to a mass audience because it is visible. It sits at the intersection of consumption, identity, and waste, and it offers clear symbols like “new” versus “reworn,” or “disposable” versus “kept.”

Early “green carpet” moments often aimed to prove that sustainability could look as polished as traditional luxury. Campaigns like the Green Carpet Challenge helped build that bridge by encouraging stars and stylists to treat materials, labor, and lifecycle as part of the look’s story. The goal was not to shame glamour but to redefine it.

Yet the red carpet has always had structural reasons to resist sustainability. Fashion houses want fresh imagery, outlets want novelty, and stars want looks that feel exclusive. A brand-new custom gown is a clean business arrangement. It is easy to secure, easy to control, and easy to market.

The turning point came when the value of “newness” changed. Social media made repetition less risky and made storytelling more valuable. A look does not need to be brand-new to be “new content.” It just needs a narrative hook that travels fast.

That is where recycled couture found its modern form. It stopped being only about eco-fabrics and started being about cultural capital. Archival fashion can signal taste, research, and confidence. Vintage couture can signal rarity. Reworked heritage pieces can signal creativity without waste. In a world exhausted by endless drops, restraint can read like power.

The Golden Globes are especially important in this shift because they sit at the front of awards season. They set the tone for what will feel current for the weeks that follow. When a sustainability-coded approach appears early, it is more likely to ripple outward.

It also helps that recycled couture fits the psychology of luxury right now. The luxury consumer is increasingly fluent in resale, authentication, and provenance. The public has learned the language of archives the way they learned the language of sneakers and streetwear. When people understand “year,” “collection,” and “reference,” archive fashion stops feeling like a compromise and starts feeling like connoisseurship.

There is a second force at work as well. Sustainability in fashion has struggled with credibility because consumers have learned to distrust vague claims. “Conscious” labels often feel like marketing. Archive dressing is harder to fake. If the piece is from 2003 or 1996, the reuse is tangible even if the impact is not perfectly measurable.

That does not mean recycled couture is automatically low-impact, fair, or inclusive. It does mean it is a format that audiences grasp quickly. In media terms, it is legible.

Below is a simple map of how the concept is being used now, not in labs or policy language, but in the reality of red carpet logistics.

| Recycled Couture On The Red Carpet | What It Usually Means In Practice | Why It Works As A Status Signal | The Tension To Watch |

| Vintage couture or archival pulls | Existing garments sourced from archives, collectors, dealers, or brand vaults, then tailored and restored | Provenance and rarity replace novelty as the flex | Access is unequal and inventory is limited |

| Reworked heritage pieces | An old look is rebuilt, updated, or reinterpreted using existing garments or deadstock | The house’s history becomes the headline | Easy to market as “circular” without clear proof |

| Rental and stylist circulation | Looks circulate through stylist networks, ateliers, and high-end rental systems | Implies sophistication and efficiency | Often invisible unless explicitly disclosed |

| Craft and longevity narratives | Time-intensive build stories position “slow” as a virtue | Labor and artistry become part of the sustainability signal | A long build time does not guarantee low-impact materials |

The bigger story is that recycled couture has become the bridge between aspiration and accountability. It lets stars participate in a cultural pivot without abandoning the drama and fantasy the red carpet is built to deliver.

What The Golden Globes 2026 Signaled On The Red Carpet?

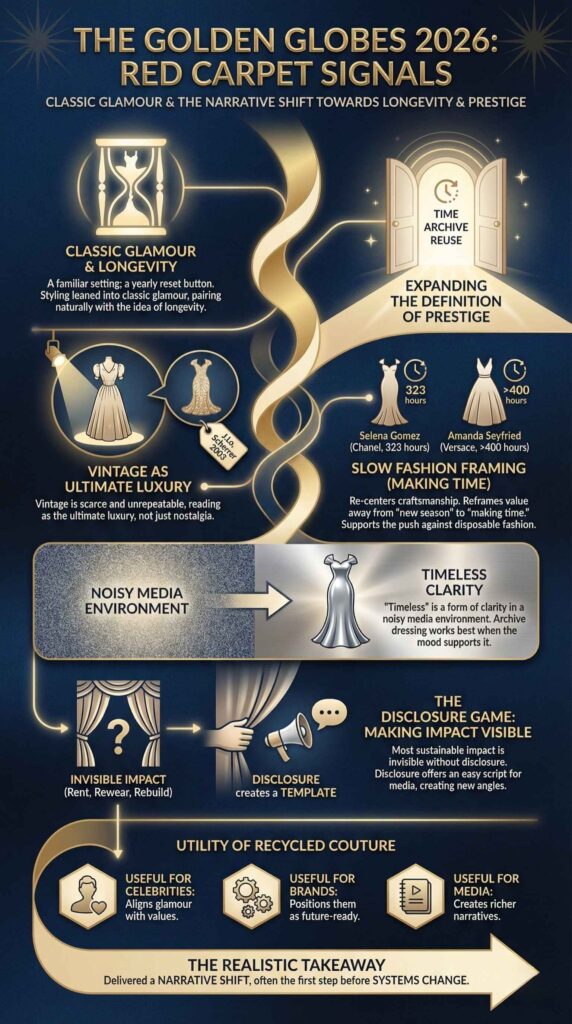

The Golden Globes 2026 took place in Los Angeles at the Beverly Hilton, a familiar setting that often functions like a yearly reset button for awards season fashion. The night’s styling leaned into classic glamour, which matters because classic glamour pairs naturally with the idea of longevity.

This was not simply a night of “eco looks.” It was a night where the fashion conversation expanded to include time, archive, and reuse as part of the definition of prestige.

One of the clearest examples was Jennifer Lopez wearing a widely reported vintage Jean-Louis Scherrer haute couture gown from 2003. In the old red carpet logic, vintage could read as nostalgia or costume. In the new logic, vintage can read as the ultimate luxury because it is scarce and unrepeatable.

At the same time, the Globes showcased another parallel trend that often gets folded into recycled couture even when the garment itself is new. That is the “slow fashion” framing, where outlets highlight the number of hours required to create a look. Selena Gomez’s custom Chanel was widely reported as taking 323 hours to make. Amanda Seyfried’s custom Versace was widely reported as taking over 400 hours.

Those hour counts do two things at once. They re-center craftsmanship at a time when audiences are suspicious of mass production. They also subtly reframe value away from “new season” and toward “making time,” which supports the broader cultural push against disposable fashion.

There is an important nuance here. A painstaking new gown can still be made from virgin synthetics or high-impact materials. So this does not automatically equal sustainability. It does, however, shape the narrative terrain in which sustainability arguments play out. If the public starts treating “slow” as desirable, it becomes easier for brands to sell durability, repair, and reuse later.

Another signal was the broader mood of the carpet. A classic, cinematic direction, including metallics and high-shine looks, can seem purely aesthetic. But it also points to the way red carpet fashion is reacting to cultural fatigue. In a noisy media environment, “timeless” is a form of clarity.

This matters for recycled couture because archive dressing works best when the overall mood supports it. If the carpet is chasing novelty for novelty’s sake, vintage can look out of place. If the carpet is leaning into icons, silhouettes, and history, archive becomes cohesive rather than disruptive.

The Globes also highlighted a reality that will define the next few years of awards season. Most sustainable impact remains invisible unless teams disclose it. If a look was rented, reworn, or rebuilt from an older garment, the audience only knows if someone says so. That means recycled couture is partly a disclosure game.

When a celebrity or brand does disclose, it creates a template others can copy. It offers an easy script for interviews and press releases. It also gives editors a new angle beyond “best dressed” and “who wore it best.”

In that sense, the Golden Globes 2026 did not just show recycled couture. It showed that recycled couture has become useful. It is useful for celebrities because it aligns glamour with values. It is useful for brands because it positions them as future-ready. It is useful for media because it creates narratives that feel richer than a pure fashion report.

The most realistic takeaway is that the Globes did not deliver a perfect sustainability shift. It delivered a narrative shift. And narrative shifts are often the first step before systems change.

Why It Matters: Culture, Carbon, Regulation, And The Economics Of Reuse?

If recycled couture were only a style story, it would fade. It matters because it connects directly to four forces that are reshaping fashion from the inside out.

First is the emissions trajectory. Industry trackers have pointed to a troubling reality: fashion’s emissions are not falling fast enough, and some datasets show they are rising again. The core driver is not a lack of slogans. It is volume, especially volume tied to synthetics like polyester.

Second is materials. Textile production continues to climb, and when production climbs faster than sustainable material adoption, the math breaks. Even if recycled polyester tonnage grows, its market share can stagnate or shrink if virgin polyester grows faster.

Third is regulation. Governments are moving from voluntary guidelines to rules that impose costs on waste, overproduction, and weak disclosure. Extended producer responsibility shifts disposal and recycling costs back toward producers. Fast-fashion regulations target the business models that depend on speed and scale.

Fourth is the consumer economy. Resale is no longer a fringe behavior. It is increasingly a mainstream channel that changes how people assign value to used clothing. When secondhand grows faster than retail apparel, it creates a cultural and logistical foundation for reuse at every level, including the red carpet.

The key point is that recycled couture is not only a moral signal. It is becoming an economic signal.

Here are the numbers and indicators that explain why the pressure is rising.

| Indicator | Recent Reported Signal | What It Suggests | Why It Connects To Red Carpets |

| Apparel emissions | Emissions increases reported by industry trackers, tied to production growth and virgin polyester reliance | The current pace of change is not aligned with climate goals | High-visibility events amplify scrutiny of “wear once” norms |

| Global fiber production | Recent reports note record or near-record fiber output, with polyester dominating | Substitution alone cannot offset rising volume | Archive fashion becomes a cultural counterweight to growth |

| Recycled fiber share | Industry reporting shows recycled shares remain limited and can fall as virgin output rises | Scaling recycling is hard and slow | Reuse becomes the fastest “available now” circular option |

| Resale market growth | Secondhand projections show rapid growth through the end of the decade | Consumers are normalizing pre-owned value | Stylists gain deeper sourcing pools for vintage and archive |

| Policy direction | EPR programs and fast-fashion restrictions advance in major markets | Compliance costs are coming | Brands rehearse future-facing messaging on red carpets |

From a culture perspective, recycled couture functions like a public demonstration of a different value system. It shows that a high-status person can wear something old and still command attention. That challenges one of the deepest engines of fashion consumption, which is the belief that status requires constant novelty.

From a carbon perspective, the recycled couture story is compelling because it aligns with what circular economy advocates often say is the simplest first move. Keep products in use longer. If a garment already exists, the most immediate way to reduce impact is to extend its life and reduce demand for new production.

From a regulation perspective, the red carpet is not separate from policy. Brands use celebrity dressing as marketing. When regulators push for transparency and circularity, brands have an incentive to build public narratives that support their compliance posture. “We value longevity” plays better than “we sell volume.”

From an economics perspective, resale growth has changed how consumers think about value retention. A dress that can be resold has a different identity than a dress designed to be disposable. This mindset is now bleeding into luxury, where provenance and resale value increasingly function like quality signals.

Still, it is important to acknowledge the counter-argument. A few archive looks do not change the industry’s production volume. A single red carpet night does not build recycling plants. And some “recycled couture” messaging can drift into greenwashing when the story focuses on glamour while the supply chain remains unchanged.

That critique matters because it defines what comes next. The next phase will demand proof. It will demand that sustainability is not only aesthetic but operational.

This is also where the conversation gets more complex. Recycled couture can create unintended consequences. It can turn vintage supply into a scarcity market that excludes smaller stylists and independent talent. It can encourage hidden shipping, last-minute air freight, and restoration processes that carry their own impacts. It can also become a branding shortcut where “archive-inspired” is sold as “circular.”

So why does it still matter?

Because cultural norms often shift before industrial systems do. When culture shifts, it creates space for regulations, investments, and business model changes to land without backlash. If people come to believe that reuse is compatible with prestige, brands can invest in reuse infrastructure without fearing it will dilute their image.

This is why the Golden Globes 2026 moment is bigger than the dresses. It is a test of whether audiences are ready to see glamour and restraint as compatible. It is also a test of whether brands can move beyond the symbolism and into measurable action.

Who Gains And Who Pays If Recycled Couture Becomes The New Red Carpet Default?

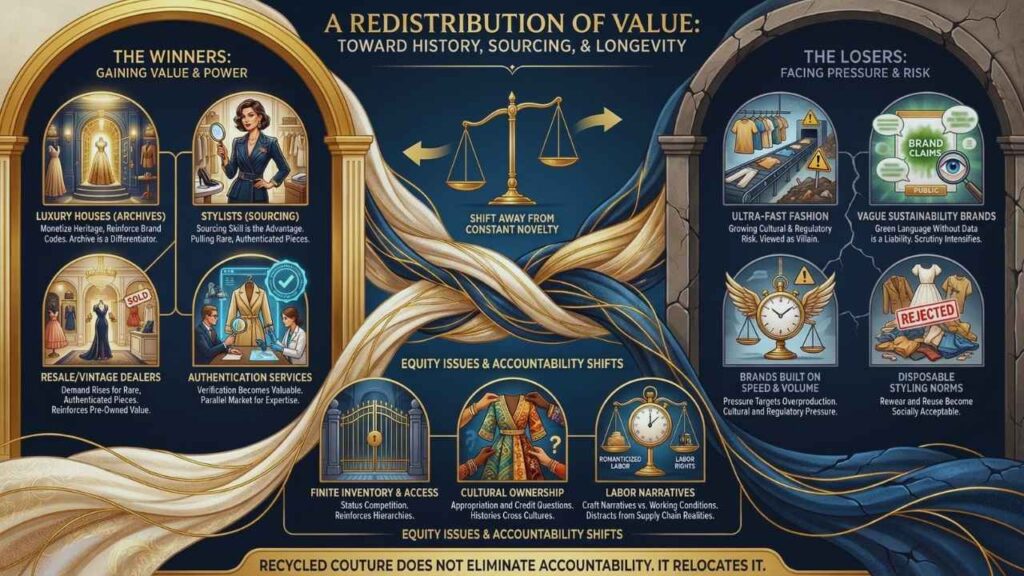

Recycled couture will not scale evenly. It will create winners and losers, and those incentives will determine whether the trend becomes a durable shift or a short-lived aesthetic.

Luxury houses with deep archives stand to gain. Archive dressing allows them to monetize heritage, reinforce brand codes, and generate press without relying exclusively on new seasonal product. In a crowded luxury market, the archive is a differentiator competitors cannot easily copy.

Stylists stand to gain power as well. The more red carpets reward vintage and archival references, the more value sits in sourcing skill. A stylist who can pull a rare piece, secure authentication, and build a coherent story has an advantage over someone who only books new-season loans.

Resale platforms and high-end vintage dealers also stand to gain. If awards season continues to normalize archive dressing, it reinforces the idea that pre-owned items can be top-tier. That can push more consumers toward resale, which strengthens the entire ecosystem that makes recycled couture logistically possible.

Authentication and provenance services become more valuable in this world. The more money and attention flow into vintage couture, the more brands and collectors will demand verification. That creates a parallel market for expertise that did not matter as much when the dominant red carpet look was brand-new and traceable.

On the other side, ultra-fast fashion faces growing cultural risk. Even if fast fashion is not directly competing with couture, it competes for mindshare and sets the tone for consumption norms. As governments move toward restrictions and penalties, and as the public conversation centers more on overproduction, fast fashion becomes easier to frame as the villain.

Brands that rely on vague sustainability claims face risk as well. If regulation and consumer skepticism intensify, “green” language without data becomes a liability. In that environment, archive and reuse stories can feel safer because they are concrete.

There is also a deeper equity issue. Archive couture is finite. If recycled couture becomes a status competition, it could become another system where only the most connected teams can access the best inventory. That can reinforce hierarchies within celebrity culture and within fashion labor.

A second equity issue involves cultural ownership. Vintage and archival looks often carry histories. When those histories cross cultures, the styling choices can raise questions about appropriation, respect, and credit. Recycled couture is not automatically ethical simply because it is reused.

There is a third issue as well. Craft narratives that focus on hundreds of hours can unintentionally romanticize labor without addressing labor rights. A time-intensive gown can be a celebration of skilled artisanship, but it can also distract from the working conditions and wage realities of the broader supply chain.

So recycled couture creates a new set of accountability questions. It does not eliminate accountability. It relocates it.

Here is a practical view of how incentives may line up if this becomes the dominant awards-season trend.

| Likely Winners | Why They Benefit | Likely Losers | Why They Face Pressure |

| Luxury houses with strong archives | Heritage becomes a renewable marketing asset | Brands built on speed and volume | Cultural and regulatory pressure targets overproduction |

| Stylists with sourcing networks | Sourcing becomes the main creative advantage | Teams without access to archives | Scarcity and gatekeeping limit participation |

| High-end resale and vintage dealers | Demand rises for rare, authenticated pieces | Vague “sustainable” marketing | Scrutiny increases as policy and media mature |

| Authenticators and provenance experts | Verification becomes valuable as stakes rise | Disposable styling norms | Rewear and reuse become socially acceptable |

| Textile-to-textile recyclers | Visibility and policy increase investment potential | Bottle-based “recycling” narratives | Industry shifts toward true circularity demands |

The takeaway is not that recycled couture is purely good or purely bad. The takeaway is that it is a redistribution of value. It shifts value toward history, sourcing, and longevity, and away from constant novelty.

If that redistribution continues, fashion’s business model begins to look different. Not overnight, but directionally.

What Happens Next: The New Rulebook For Awards Season Sustainability?

If recycled couture is truly “back,” the next question is what it turns into. Awards season will provide the answer because it will repeat the experiment across multiple events, multiple stylists, and multiple brand strategies.

Here are the most plausible next steps, stated as forward-looking analysis rather than certainty.

First, disclosure will become part of the performance. In the same way that brands now distribute detailed press notes about jewelry and makeup, they will increasingly distribute notes about sourcing and lifecycle. The audience is learning to ask, “Is it archival?” Media will reward teams that can answer clearly.

Second, we will likely see more formal archive programs from luxury brands. Instead of ad hoc vault access, brands may build structured pathways for celebrities to wear archive pieces, with clearer documentation, stronger storytelling control, and sometimes commercial tie-ins like exhibitions, auctions, or museum partnerships. This gives brands the benefits of reuse while maintaining control over scarcity.

Third, resale and rental will continue to professionalize. If secondhand keeps growing, it will provide more inventory, better logistics, and more reliable authentication. That reduces the friction that currently makes archive dressing difficult. When friction drops, adoption rises.

Fourth, regulation will push the industry toward measurable definitions. “Recycled” cannot remain a loose word if governments require producer responsibility and stricter claims. The likely outcome is a shift from marketing language to standardized language, including clearer categories such as recycled content percentages, verified recycled fibers, and documented reuse.

Fifth, textile-to-textile recycling will become more central to the sustainability story, even if it stays mostly invisible to viewers. The industry has already signaled growing interest in recycling systems that can turn old garments into new fibers at scale. This shift will be driven by policy deadlines, brand commitments, and the reality that bottle-based recycling cannot be the long-term answer for a textile-dominant waste stream.

Sixth, a backlash cycle is possible. Some audiences may start treating sustainability messaging as performative if it does not align with broader behavior like private jet usage, excessive outfit changes, or constant new wardrobe churn. That backlash could push celebrities toward fewer claims and more action, or it could push the conversation back toward pure fashion.

Seventh, we should watch for a shift in what “best dressed” means. If editors and audiences begin to reward repeat wear and archive use, then the incentives change. A celebrity could wear the same silhouette multiple times and be praised for consistency rather than criticized for repetition. That would be a real cultural shift because it changes the core social pressure that drives overconsumption.

To make this concrete, here is a timeline that blends the cultural build-up with the policy and market forces now shaping what recycled couture can become.

| Year Or Window | Cultural Signal On Red Carpets | Market Or Policy Signal | Why It Builds Toward 2026 And Beyond |

| 2009 to early 2010s | Early campaigns push ethical glamour and “story behind the look” | Sustainability enters luxury consulting and events | Builds a language and a network for sustainable styling |

| 2016 to 2020 | High-profile recycled and reworn statements become widely covered | Growing public climate awareness | Makes sustainability legible to mainstream audiences |

| 2020 to 2023 | More vintage and rewear moments, but uneven adoption | Circular fashion gains consumer traction | Normalizes the idea that pre-owned can be premium |

| 2024 to 2025 | Awards-season vintage becomes more common in coverage | EPR momentum grows, fast fashion regulation advances | Turns sustainability into compliance and cost, not only branding |

| 2026 | Golden Globes reward archive and “slow fashion” narratives early in the season | Resale projections and fiber production data highlight scale challenges | Creates a high-visibility test of whether reuse can become a default |

| 2027 to 2030 | Predicted rise in disclosure norms and archive programming | Policy deadlines and penalties accelerate circular systems | Forces definitions, infrastructure investment, and measurable progress |

So what comes next for recycled couture is not only more vintage looks. It is a broader rewrite of the red carpet’s operating system.

Prediction, clearly labeled: If regulators continue to expand producer responsibility and if resale continues to grow at projected rates, recycled couture will become less of a trend and more of a baseline expectation. The most influential stars will still wear custom looks, but they will increasingly frame them through durability, repair, reuse, and verified materials rather than only novelty.

The Golden Globes 2026 mattered because it showed a credible new prestige signal. When a culture that once worshiped “new” starts praising “kept,” it opens the door for systems change. The next challenge is whether fashion will back the symbolism with infrastructure and data, so recycled couture becomes more than a beautiful story.