France’s “screen ban” debate is a turning point because it treats teen social media harm as a product-design and governance problem, not just a parenting issue, and it tests whether a democracy can curb addictive feeds like infinite scroll without creating a privacy-heavy age-check system.

Key Takeaways

- The France Infinite Scroll Ban conversation is really about regulating “attention capture” mechanics, not only policing content.

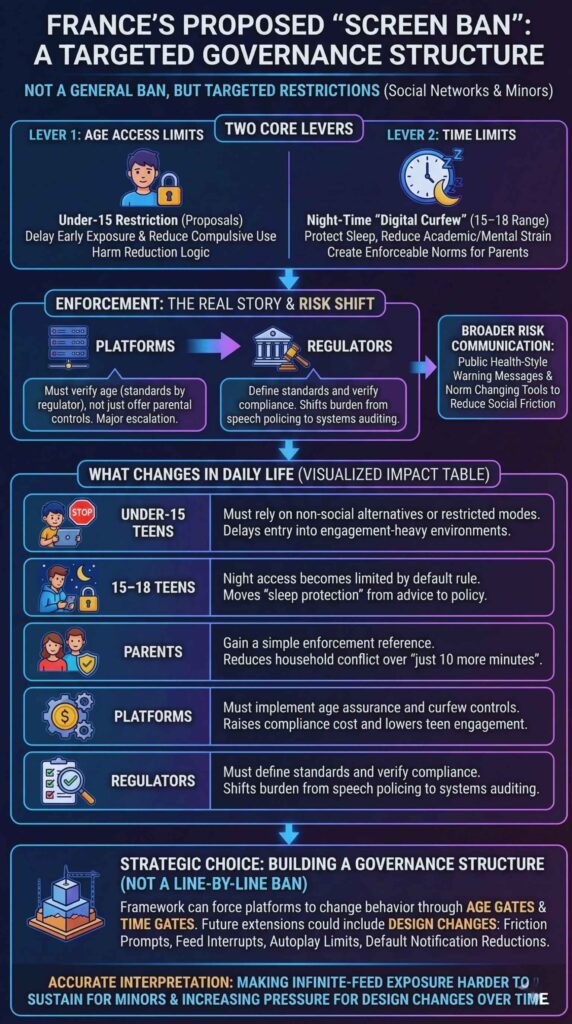

- France’s proposal leans on an under-15 access restriction and a night curfew for older teens, then forces platforms to prove age compliance.

- The EU is building parallel guardrails through Digital Services Act guidance and age-assurance infrastructure, which could decide whether France’s plan works in practice.

- The hardest trade-off is age verification: too weak and kids bypass it, too strict and everyone faces identity checks.

- If endless-feed mechanics get constrained for minors, the impact will ripple into ad markets, creator economics, product design norms, and future AI companion regulation.

France is trying to convert a widespread cultural anxiety into enforceable rules. The public story sounds simple: teenagers spend too long on social apps, sleep less, feel worse, and parents feel powerless. The policy story is more ambitious. France is moving toward a framework that treats certain platform behaviors as structurally risky for minors, especially design choices that remove stopping cues and keep users in a loop.

That shift matters because it changes what governments believe they are regulating. Instead of chasing harmful posts one by one, lawmakers increasingly focus on how platforms shape behavior at scale: algorithmic ranking, autoplay, push notifications, and the frictionless mechanics behind infinite scroll. Those mechanics sit at the center of modern platform revenue. Target them for minors and you do not just “protect children.” You also test whether the attention economy can be partially de-optimized by law.

France also sits in a uniquely influential position. It can experiment with national rules, but it also operates inside the European Union, where cross-border services and EU-level digital law constrain what a single country can enforce. That creates a real-world laboratory for a broader question: can Europe build a coherent model that protects minors without turning the internet into an ID checkpoint?

How France Got Here: From School Phone Rules To Algorithm Anxiety?

France’s current stance did not appear from nowhere. It builds on a sequence of steps that gradually reframed screens from “personal choice” to “public policy.”

France began with institutions. A national restriction on mobile phones in schools, introduced years earlier, carried a simple logic: even if families disagree about screen habits at home, schools can declare protected time for attention, learning, and social interaction. That decision made screens a collective governance topic, not merely a household preference.

Then came the frustration phase. France attempted to establish rules around minors and social networks, but implementation ran into legal and practical barriers, including compatibility questions in the EU context. This created an important political lesson: national governments can announce “digital majority” concepts, but they struggle to enforce them on platforms that operate across borders and update features weekly.

Next came agenda-setting by experts and commissions. French policy debate began to borrow language from behavioral science, describing “attention capture” as a system with incentives, engineering teams, and business metrics, not just “kids being kids.” The message that stuck was that modern feeds do not only deliver entertainment. They are built to maximize time and repetition, often by removing natural endpoints.

Finally came a platform-specific flashpoint that made the abstract tangible. Parliamentary inquiries and consultations gathered large volumes of testimony from families, educators, and young people, focusing heavily on TikTok’s recommendation patterns and the emotional spiral created by algorithmically reinforced content sequences. Even when the political headline names one platform, the regulatory intent usually targets the model shared across many apps: engagement-first ranking plus endless consumption.

A useful way to understand the trajectory is that France moved through three policy frames:

- Education frame: protect classroom attention and reduce disruption.

- Health and development frame: treat excessive use as a risk to sleep, well-being, and self-regulation.

- Market design frame: treat addictive mechanics as a product and governance problem.

The France Infinite Scroll Ban conversation lives in that third frame. It implies that society can set rules for how products may seek attention from minors, similar to how societies set rules for marketing, safety labeling, and youth exposure in other industries.

Here is a concise timeline of the policy arc that pushed France to this moment:

| Period | What Shifted | What France Started Debating |

| Late 2010s | Schools and families confront constant distraction | Institutional limits on devices in school settings |

| Early 2020s | Platforms become central teen social infrastructure | Whether “social participation” requires platform membership |

| Mid 2020s | EU digital law expands platform duties | How to align national rules with EU enforcement tools |

| 2024–2025 | Testimony and inquiry politics accelerate | Whether algorithmic loops deserve special restrictions for minors |

| 2026 horizon | Age assurance tech matures in Europe | Whether enforcement can avoid privacy overreach |

This background matters because it explains why France’s current effort is not a single moral panic. It is a continuation of a multi-year attempt to find enforceable levers that match how platforms actually operate.

What The Proposed “Screen Ban” Tries To Change?

Despite the “screen ban” label, France is not proposing a general ban on screens. It is building a targeted set of restrictions around social networks and minors, using two core levers: age access limits and time limits.

The age lever aims to reduce early exposure. Proposals discussed in France’s legislative debate have centered on restricting access to social networks for younger teens, commonly under 15. The logic is preventative. If policymakers believe early exposure increases compulsive use and raises vulnerability to harmful content loops, then delaying entry becomes a form of harm reduction.

The time lever aims to protect sleep and create enforceable norms. A night-time “digital curfew” for older minors, often framed around the 15–18 range, focuses on the hours when compulsive use tends to intensify and when sleep disruption creates next-day academic and mental strain. A curfew also serves a political purpose: it offers parents a rule they can point to that does not depend on constant negotiation inside the household.

The enforcement lever is the real story. France’s draft approach pushes responsibility onto platforms to verify age, potentially under standards defined by a regulator. That is a major escalation from “offer parental controls.” It becomes “prove you keep minors out or limit them, or face penalties.”

France’s policy package also signals a broader shift in how it communicates risk. Beyond access and curfew, proposals have included warning-style messaging and consumer-information tools intended to change norms, not just behavior. This resembles public health tactics: communicate risk consistently, shape expectations, and reduce the social friction families face when enforcing limits.

To understand the policy intent, it helps to map what changes for each group if France implements an under-15 restriction plus a night curfew and age checks.

| Group | What Changes In Daily Life | Why It Matters Politically |

| Under-15 teens | Must rely on non-social alternatives or restricted modes | Delays entry into engagement-heavy environments |

| 15–18 teens | Night access becomes limited by default rule | Moves “sleep protection” from advice to policy |

| Parents | Gain a simple enforcement reference | Reduces household conflict over “just 10 more minutes” |

| Platforms | Must implement age assurance and curfew controls | Raises compliance cost and lowers teen engagement |

| Regulators | Must define standards and verify compliance | Shifts burden from speech policing to systems auditing |

This approach also carries a subtle but important strategic choice. France is not trying to ban one feature line-by-line in one law. Instead, it is building a governance structure that can force platforms to change behavior through age gates and time gates. That structure could later be extended to design changes like friction prompts, feed interrupts, autoplay limits, and default notification reductions for minors.

So when people say “France bans infinite scroll,” the more accurate interpretation is: France is trying to build a legal framework that makes infinite-feed exposure harder to sustain for minors, and that increases pressure for design changes over time.

Why Infinite Scroll Is Now A Regulatory Target?

Infinite scroll became a symbol because it captures the logic of the attention economy in one gesture: no stopping point, no natural exit, constant novelty, and a reward system shaped by recommendation algorithms.

In earlier decades, media consumption had built-in friction. Newspapers ended. TV schedules ended. DVDs ended. Even cable had commercial breaks and episode boundaries. Social feeds removed those boundaries, then added personalization to make the next item more likely to hold you. For adults, that can look like convenience. For minors, policymakers increasingly see it as an engineered vulnerability exploit.

The deeper reason regulation is moving toward design is that content moderation alone cannot address the “time problem.” Even if platforms removed the worst content, the system could still keep minors online for hours. Policymakers now treat excessive use as its own category of harm, partly because it links to sleep loss and displacement of offline activities, and partly because long sessions increase the chance of encountering risky content.

Europe’s debate also reflects a competition between two regulatory theories:

- Content theory: harm comes from what teens see.

- Systems theory: harm comes from how platforms keep teens engaged and how ranking systems steer attention.

The France Infinite Scroll Ban debate is systems theory in action.

A practical way to see the difference is to compare the policy tools that match each theory.

| Regulatory Theory | Typical Tool | Limits |

| Content theory | Remove or downrank harmful posts, enforce moderation | Hard to define harm consistently, high speech sensitivity |

| Systems theory | Limit engagement mechanics, impose friction, require risk audits | Harder to measure causality, requires technical oversight |

| Hybrid approach | Age gates plus safety duties plus design constraints | Complex enforcement, risk of privacy-heavy verification |

France appears to be moving toward a hybrid. It targets minors directly through access and curfew, while leaning on EU-level platform safety expectations to push risk reduction. That hybrid approach tries to avoid the weakest point of content-only regulation: it is reactive and endless, because platforms produce new content at enormous scale.

The other reason infinite scroll matters is economic. Infinite scroll is not only a “feature.” It is a revenue pathway. More time-on-app means more ad impressions, more data signals, and a tighter feedback loop for personalization. Restrict infinite consumption for minors and you reduce the value of teen audiences.

This is where the analysis gets uncomfortable, and why the debate will intensify. Teen attention is valuable for three reasons:

- It anchors long-term customer habits.

- It shapes cultural trends and creator economies.

- It builds identity-linked social graphs that are hard to leave later.

Regulation that delays entry or reduces nightly use threatens that pipeline. That does not mean it is wrong. It means platforms will fight it, redesign around it, and lobby aggressively.

Still, policymakers have a reason to believe systems regulation can work better than content regulation. Systems regulation allows measurable compliance checks:

- Does the platform prevent underage accounts?

- Does it enforce curfew restrictions for minors?

- Does it reduce addictive mechanics for teen accounts by default?

- Does it publish risk assessments and mitigation reports?

Those are auditable questions. Even if science cannot perfectly isolate “infinite scroll causes anxiety,” regulators can still enforce whether a company built guardrails and whether those guardrails change usage patterns.

Here is a set of “key statistics” that typically shape this policy push, and why each statistic matters more than the headline number.

- Problematic social media use measures have risen in major international adolescent surveys across multiple countries over recent years. Policymakers interpret this as a signal of a systems-level shift, not an individual moral failing.

- Large cross-country analyses often find associations between very high daily screen time and lower well-being, while also warning that sleep deprivation and broader social stressors may be even stronger predictors. Policymakers interpret this as a reason to prioritize sleep protection tools like curfews.

- National consultations in France drew tens of thousands of testimonies in inquiries related to teen experiences on algorithmic platforms. Policymakers interpret this as political legitimacy to act, even if the scientific picture remains complex.

Those inputs do not prove a single design feature is the culprit. They do support the political claim that voluntary controls have not stabilized the problem, and that governments now feel compelled to move upstream into product design and default settings.

The Implementation Problem: Age Assurance, Privacy, And Platform Workarounds

Every policy that restricts minors online hits the same wall: enforcement.

If a law says “under-15s cannot access social networks,” the platform must reliably know who is under 15. But if a platform asks everyone for a passport scan, society creates a different risk: identity checkpoints for everyday speech and browsing.

This creates a three-way tension:

- Accuracy: the system must actually keep underage users out.

- Privacy: the system must not collect excessive sensitive data.

- Usability: the system must not be so annoying that everyone bypasses it.

France’s approach points toward regulated standards for age verification rather than letting each platform improvise. That is important because improvised solutions tend to fail in predictable ways: they either become too invasive, too weak, or too easy to circumvent.

Europe’s broader direction suggests an attempt to solve this with privacy-preserving “age assurance,” where the user can prove they are above an age threshold without sharing their full identity. If Europe can implement that at scale, France’s proposal becomes far more practical. If Europe cannot, France’s rules either become symbolic or drift toward intrusive verification.

Platforms, meanwhile, will look for workarounds. The most likely workarounds include:

- Account migration: teens move to less regulated platforms or messaging-based communities.

- Misreporting: users simply lie about age unless verification is strong.

- Proxy accounts: older siblings or adults create accounts for younger teens.

- Feature rebranding: platforms argue they are not “social networks” under the definition, similar to past fights over what counts as “video sharing” or “messaging.”

This matters because governments often underestimate how quickly platforms adapt product classification. A service can shift from “social network” to “entertainment app” to “AI companion” with minimal UI changes, while preserving the same engagement mechanics. That is why the European debate has started to include not only social media but also video platforms and even conversational AI experiences used by minors. The policy target becomes broader: any system that can keep minors engaged indefinitely.

France also must confront a measurement problem. To defend enforcement, regulators will need metrics that show the law has meaningful outcomes. The most defensible near-term metrics will likely focus on usage patterns rather than mental health claims, because usage is easier to measure.

Here are the kinds of metrics France and the EU can plausibly audit if such rules take effect:

| Metric Type | What Can Be Measured | Why It Is Politically Useful |

| Access compliance | Share of minor accounts successfully blocked | Shows whether the rule has teeth |

| Time compliance | Night-time usage reduction for teen accounts | Links to sleep protection narrative |

| Design compliance | Default settings that reduce addictive loops for minors | Demonstrates systemic mitigation |

| Transparency | Public reporting on risk mitigation and enforcement | Builds trust and enables scrutiny |

None of these metrics require claiming “law X reduced depression by Y%.” That kind of claim takes years and remains contested. But governments can still argue that reducing late-night compulsive use and limiting early exposure is a precautionary approach, similar to other youth protection standards.

Privacy advocates, however, will still push back if age assurance becomes too identity-heavy. The legitimacy of France’s approach will depend on whether it can credibly claim that it protects minors without forcing a broad identity layer on the entire population.

What Comes Next For France, Europe, And The Attention Economy?

The next phase will likely unfold in steps rather than one dramatic “ban day.”

First, France will face a legislative and operational test: can it define covered services clearly, establish realistic enforcement standards, and coordinate with EU rules? The EU context matters because platforms do not operate as French-only entities. A national law can set expectations, but platforms will look to EU frameworks as the real compliance baseline.

Second, age assurance infrastructure will become the hinge. If Europe advances privacy-preserving verification tools and makes them easy to integrate, then laws like France’s become enforceable without mass identity collection. If age assurance remains patchy, the system either fails or becomes intrusive.

Third, the policy conversation will likely expand from age and time limits into design constraints for minor accounts. Even if France does not explicitly outlaw infinite scroll in one clause, regulators can push product changes through compliance expectations: feed interruptions after a set time, autoplay off by default for minors, notification throttling at night, and friction prompts that restore stopping cues. Over time, these measures can approximate a functional limit on endless scrolling without needing to police UI pixel-by-pixel.

Fourth, businesses tied to teen attention will adjust. Advertising strategies will pivot toward older audiences or toward contexts where verification is easier. Creators will diversify distribution, leaning more on platforms that remain accessible, or shifting to formats with less regulatory pressure. Publishers and media companies may see both risk and opportunity: risk if youth referral traffic drops, opportunity if regulated friction increases demand for curated, finite content.

A practical way to see the economic implications is a winners-versus-losers snapshot if France’s approach spreads.

| Likely Beneficiaries | Why | Likely Pressured | Why |

| Sleep and health advocates | Policy aligns with prevention and habit formation | Engagement-driven platforms | Lower teen minutes reduce reminders, ads, and growth |

| Parents and schools | Clear norms reduce conflict and distraction | Ad tech targeting youth | Less signal data and fewer impressions |

| Privacy-preserving ID providers | Demand for age assurance tools increases | Smaller creators reliant on teen virality | Less reach in the most trend-driven cohort |

| “Finite content” products | More appeal if endless feeds face friction | Platforms with weak moderation | More scrutiny and compliance costs |

The fifth and biggest consequence is normative. If France and the EU succeed in limiting addictive mechanics for minors, they establish a precedent: “product design that exploits developmental vulnerabilities is regulatable.” That precedent will not stop at social apps. It will move into AI companions, recommendation-heavy streaming, and any interface that aims to maximize session length.

Here are the milestones to watch through 2026, framed as observable events rather than speculation:

- Whether France finalizes enforceable definitions of covered services and age thresholds.

- Whether France’s regulator publishes concrete compliance standards for age assurance and curfew mechanisms.

- Whether EU-wide age assurance systems become usable enough that platforms adopt them at scale.

- Whether platforms introduce “teen account” defaults that materially reduce addictive mechanics, especially at night.

- Whether early data shows meaningful reductions in late-night usage among teen accounts in France.

It is reasonable to predict, with clear labeling, that policymakers will start where political legitimacy is strongest: minors. Analysts suggest that if restrictions work for minors without severe backlash, the logic will expand into broader “right not to be disturbed” expectations and ethical design standards. Market indicators also point to rising demand for tools that prove age thresholds while minimizing data sharing, because that becomes the only route to enforceability without public backlash.

France is not only banning screens. It is asking whether democratic societies can rewrite the incentives of attention-based products for the youngest users, and whether Europe can do it with guardrails that protect privacy as fiercely as they protect children.