Nvidia’s Thor-era autonomy push and Jensen Huang’s praise for Tesla FSD land as the industry finally ships city-street automation. This isn’t just chips. It’s a platform war over data, sensors, safety cases, and who defines “good enough” autonomy.

Jensen Huang’s decision to call Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (FSD) “state-of-the-art” and “hard to criticize” is more than executive courtesy. It is a strategic tell about where the real fight is moving next: from headline demos to scalable, regulator-ready autonomy products, delivered either as a vertically integrated stack (Tesla) or as a reusable platform sold to everyone else (Nvidia).

How We Got Here

Autonomy has always been two races running in parallel.

One race is about capability: getting the car to perceive, predict, and act safely in the messy long tail of real roads. The other race is about industrialization: packaging that capability into something automakers can buy, certify, update over the air, and defend in court.

Tesla has spent a decade betting that its advantage comes from full-stack ownership, including its own in-car computer and end-to-end learning approaches trained on massive volumes of fleet video. Tesla’s push toward custom autonomy hardware was publicly detailed during its 2019 Autonomy Day, and Tesla maintains an upgrade pathway for customers whose vehicles need a newer “FSD computer.”

Nvidia, by contrast, is trying to make autonomy a repeatable computing product category. Its pitch is that autonomy is built on three computers working as a loop: data-center training, simulation for synthetic data, and an in-vehicle computer to run the stack in real time. That framing matters because it signals Nvidia is selling an “autonomy factory,” not just a chip.

That is why “Thor” is central to this story. Thor is Nvidia’s attempt to become the default vehicle computer for the software-defined car, while the reasoning-model push it previewed at CES 2026 is Nvidia’s attempt to move autonomy beyond pattern-matching into behavior that can better handle edge cases.

Key Statistics That Frame The Stakes

- Nvidia has reported automotive revenue growth that reflects rising OEM adoption of centralized compute and AI stacks, and it continues positioning automotive as a meaningful long-term growth driver.

- Mercedes has said it plans to bring a supervised city-street system to the U.S. in 2026 and explicitly positioned it against Tesla’s FSD, naming Nvidia’s platform in the stack.

- Waymo has reported operating a large-scale robotaxi service with substantial weekly paid ride volume and a fleet in the thousands across multiple markets.

- NHTSA’s crash reporting regime for automated systems has raised the regulatory and reputational cost of broad deployment, increasing pressure for auditable safety cases.

- Nvidia’s DRIVE Hyperion direction and partner ecosystem underscore a redundancy-first philosophy many regulators and safety engineers favor.

Nvidia Thor vs Tesla FSD, Side By Side

| Dimension | Nvidia Thor And DRIVE Hyperion Approach | Tesla FSD Approach |

| Core strategy | Sell a reusable autonomy platform to many OEMs and mobility operators | Build the full stack to optimize around one fleet and one product roadmap |

| Sensor philosophy | Sensor fusion, including radar and lidar in reference designs and partners | Camera-first approach as a defining strategic bet, optimized via fleet learning |

| Go-to-market | “Autonomy as infrastructure” for automakers and robotaxi partners | “Autonomy as a feature” sold to owners, with longer-term network ambitions |

| Product framing | Platform plus tools: training, simulation, and in-vehicle compute | Fleet learning plus product iteration through OTA updates |

| Risk posture | Spread across customers, but must work across many vehicle designs | Concentrated in one brand, but can iterate quickly across a controlled fleet |

This is the first big takeaway: “Thor vs FSD” is not only a performance contest. It is a contest between two industrial strategies for turning autonomy into a durable business.

Platform Wars: Open Ecosystems vs Vertical Integration

Huang praising Tesla while promoting Nvidia’s autonomy stack is not contradictory. It is a classic platform play.

If Tesla is the Apple-style model (hardware, software, distribution, and data under one roof), Nvidia is positioning itself as the Android-style model (a powerful, broadly licensed stack that enables hundreds of brands to compete). The point of praising Tesla’s technical achievement is to validate the destination, AI-first autonomy, while arguing Nvidia can accelerate the rest of the industry’s path to it.

This matters because most automakers do not want to become AI companies from scratch. They want to buy an autonomy-grade computer, a validated sensor suite, safety-certified middleware, and a development toolchain that reduces time to market.

The catch is the same catch platforms always face: openness can become fragmentation. “Works for everyone” is harder than “works for our cars.” Tesla can shape hardware, cameras, calibration, and data collection as one system. Nvidia must make a system that survives different vehicle architectures, supplier constraints, and regional regulations.

That is why the real fight is shifting from flashy demos to repeatable deployment. The company that wins mindshare in the “how do we ship this safely and at scale?” conversation shapes the market.

The Sensor Debate Is Becoming A Safety Case, Not A Preference

The autonomy industry has learned the hard way that technical arguments become legal arguments the moment a product ships broadly.

Nvidia’s posture leans toward redundancy: sensor fusion and reference platforms that include lidar, radar, and cameras. Its partnerships and reference-platform direction implicitly argue that redundancy is the most defensible path under scrutiny in poor visibility, complex intersections, and rare edge cases.

Tesla has taken a different bet: if the world is navigated by humans primarily using vision, then an AI trained on enough video should be able to drive with camera-based perception, backed by increasingly capable planning models. Huang’s praise for FSD as “state-of-the-art” implicitly acknowledges that this bet is not fringe anymore.

So what changes in 2026?

The sensor debate is increasingly judged by deployment constraints:

- Regulators tend to prefer redundancy, especially for higher automation levels.

- Cost curves matter for scale: lidar is cheaper than it used to be, but still adds bill-of-materials and integration complexity.

- Product liability is shaped by what is “reasonable” for the industry, and reference platforms can quietly define that norm.

In other words, Nvidia is trying to set a default industry baseline where redundancy is standard practice, while Tesla is trying to prove that data and learning can replace expensive hardware redundancy. The winner may differ by geography and by automation level.

Compute Becomes The Vehicle: Why Thor Is A Strategic Weapon

“Thor” matters less as a chip name and more as a design pattern: the shift from many small electronic control units to centralized vehicle compute capable of running perception, planning, infotainment, and safety workloads with one architecture.

This is not just a technology upgrade. It changes how the auto industry competes.

A centralized computer with enough headroom turns the car into a rolling software platform. It makes OTA updates more meaningful, reduces architecture complexity, and allows automakers to ship upgrades without re-engineering dozens of separate modules.

You can see this productization already. Mercedes has described its 2026 supervised city-street system as a packaged, updatable product, and it is building on Nvidia’s compute platform narrative.

You can also see Thor’s pull in the robotaxi partnership ecosystem, where multiple companies can assemble a stack: a vehicle, an autonomy operator, a compute platform, and a deployment roadmap.

Why compute scale matters now

Compute scale changes three things that investors and regulators care about:

| Deployment Pressure | Why More Compute Helps | What It Enables In Practice |

| Larger AI models | Higher capacity perception and planning can run with lower latency | Better handling of edge cases, smoother driving behavior |

| OTA iteration | Hardware headroom means updates can be more than small tweaks | Faster improvement cycles without hardware swaps |

| Safety architecture | Monitoring, redundancy logic, and audit tools require cycles and memory | More defensible safety cases and richer telemetry |

Nvidia’s reasoning-model narrative is essentially an argument that autonomy is approaching a foundation-model era, where more compute plus better data loops can create discontinuous capability gains.

Regulation Is The Invisible Competitor

If autonomy were only a technical challenge, Tesla’s lead would be harder to contest. The complication is that autonomy products are increasingly constrained by reporting rules, audits, and public trust thresholds.

NHTSA’s crash reporting requirements created a structured pipeline for incidents involving automated driving systems and driver-assistance systems, increasing transparency expectations and tightening the consequences of ambiguous system design and marketing.

In practice, this has turned deployment into a compliance problem.

Every broad rollout now has to answer:

- What is the system’s operational design domain

- How does it fail safely

- How do we audit and report incidents

- How do we update without introducing new risk

This is an underappreciated advantage of Nvidia’s strategy: by selling to many OEMs, Nvidia can push a safety and reporting architecture that becomes common practice, and OEMs can point to supplier-grade validation and standardized tooling. Tesla, meanwhile, carries concentrated scrutiny because it owns the brand promise and the public narrative.

The Economics: Autonomy Is Becoming A Revenue Model, Not A Feature

For Tesla, autonomy has long been positioned as a margin story: software sold on top of hardware, with longer-term option value tied to mobility services.

For Nvidia, autonomy is a total-addressable-market expansion story: turning every automaker’s autonomy spend into Nvidia silicon, Nvidia toolchains, and Nvidia AI infrastructure.

This is why Nvidia’s automotive revenue trajectory matters. Even if autonomy takes longer than optimists claim, the software-defined vehicle trend still demands centralized compute, high-performance AI accelerators, and a tooling ecosystem that looks a lot like what Nvidia already sells into data centers.

And while market sizing for robotaxis varies widely, multiple research firms project rapid growth through 2030, reflecting investor belief that commercial autonomy will move from pilots into scaled operations.

| Market Snapshot (Latest Estimates Used By Industry Analysts) | Baseline | 2030 Projection | What The Numbers Really Signal |

| Robotaxi market (one major research estimate) | Low single-digit billions | Tens of billions | Investors expect a shift from pilots to meaningful fleets |

| Robotaxi market (another major research estimate) | Under $1B to ~$1B range | Mid-to-high teens billions | Uncertainty is high, but directional growth is the consensus |

These projections are best treated as directional. They explain why Nvidia is investing in platforms that reduce time-to-deploy for many customers, and why Tesla continues to treat autonomy as central to its narrative.

Winners and losers from the platform shift

| Potential Winners | Why | Potential Losers | Why |

| OEMs adopting centralized compute | Faster integration and shared tooling | OEMs stuck on fragmented legacy ECUs | Higher cost, slower update cycles |

| Sensor firms aligned with reference stacks | Embedded into default designs | Single-path sensor strategies under pressure | Harder safety-case defense in adverse conditions |

| Robotaxi operators with strong ops discipline | Better unit economics as stacks mature | Autonomy programs without scale | Too expensive to reach reliability thresholds |

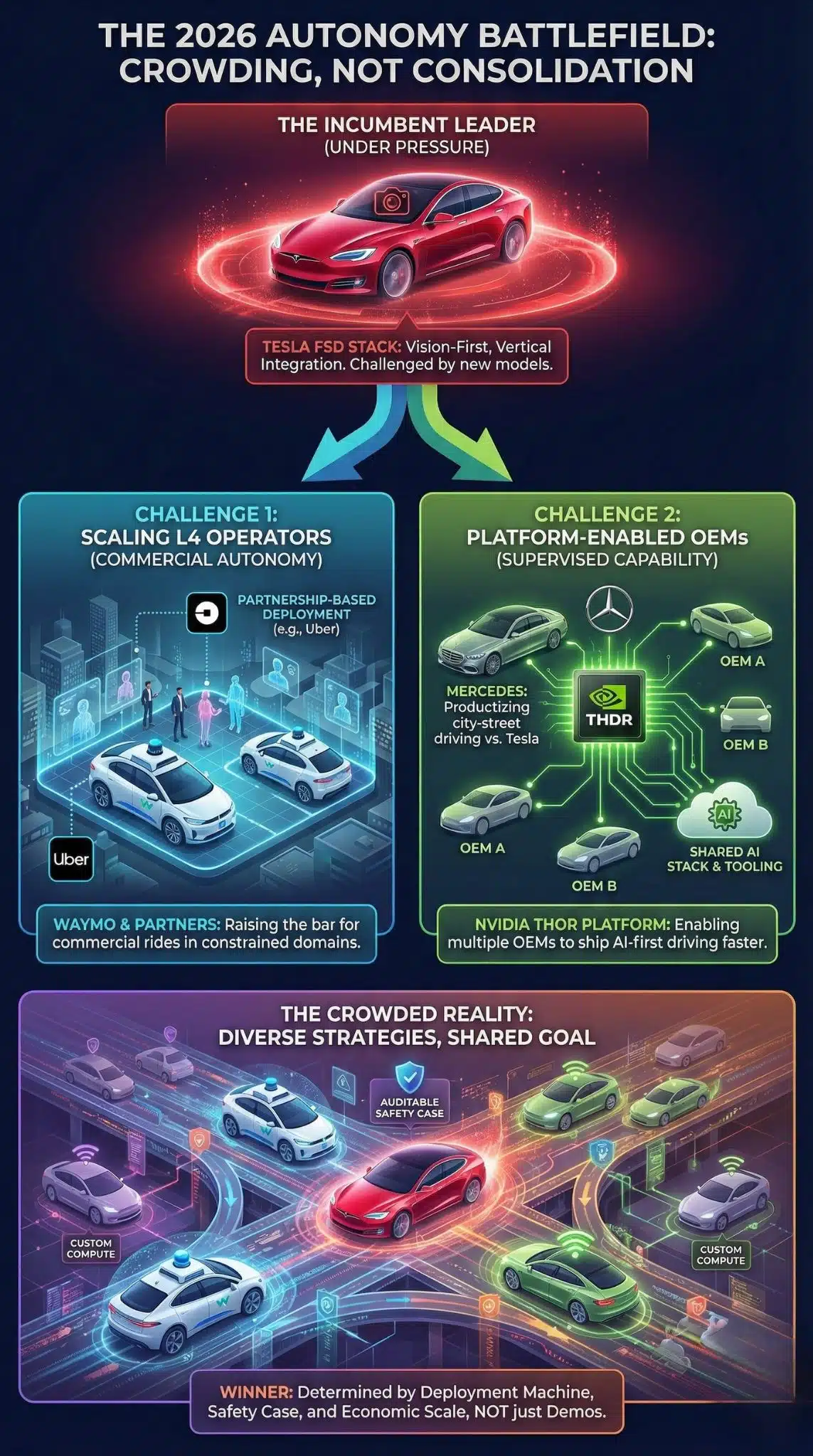

Competitive Landscape: 2026 Is Crowding, Not Consolidation

The autonomy race is getting crowded in a specific way: more companies are copying Tesla’s AI-first direction, but not copying Tesla’s vertically integrated ownership model.

- Mercedes is productizing supervised city-street driving in the U.S. and explicitly positioning it against Tesla’s FSD.

- Waymo continues scaling Level 4 robotaxi operations, raising the bar for what “commercial autonomy” means.

- Uber’s robotaxi strategy is increasingly partnership-based, where compute platforms like Nvidia’s become the glue.

- Some OEMs are signaling deeper vertical integration ambitions through custom compute, which suggests Tesla’s model is inspiring competitors even as Nvidia tries to standardize the ecosystem.

The key takeaway is that Tesla’s lead is being challenged from two directions:

- Level 4 operators proving autonomous rides at scale in constrained domains

- Platform suppliers enabling multiple OEMs to ship Tesla-like supervised capability faster

This is why Huang praising Tesla is strategically useful. It reframes the discussion from “Tesla is wrong” to “Tesla is right about the AI direction, but Nvidia can help the rest of the world catch up.”

A Timeline That Explains Why 2026 Feels Like An Inflection

| Year | Milestone | Why It Matters |

| 2016–2018 | Early era of modern autonomy compute platforms | Set the template for centralized vehicle AI |

| 2019 | Tesla publicly details its custom FSD computer strategy | Marks Tesla’s vertical integration bet |

| 2021–2023 | U.S. crash reporting framework strengthens for automated systems | Makes transparency and auditability central |

| 2025 | Automotive compute and SDV trend accelerates | Shifts budgets toward centralized AI hardware |

| Jan 2026 | Nvidia expands autonomy ecosystem and reasoning-model narrative | Signals next-phase autonomy ambitions |

| Jan 2026 | Huang publicly praises Tesla FSD | Validates AI-first autonomy while sharpening platform competition |

Expert Perspectives And The Neutrality Check

A sober reading of 2026 autonomy is that both approaches can be “right,” but under different constraints.

The Tesla case:

- Fleet-scale data and tight integration can drive fast iteration and rapid feature rollout.

- Concentrated scrutiny increases reputational risk and forces clearer safety narratives.

The Nvidia case:

- Nvidia can industrialize autonomy by packaging compute, simulation, and tooling into a shared stack.

- Platform autonomy must survive messy integrations, supplier politics, and slow model-year cycles.

A key counter-argument, often raised by transportation policy researchers and urban mobility analysts, is that robotaxis are not universally beneficial in every city. Even if the technology works, the externalities of large fleets, including congestion and deadheading, can complicate adoption in dense, transit-rich regions. That perspective matters because it can shape how fast regulators and cities open the door for autonomy at scale.

So the most neutral conclusion is not “Thor beats FSD” or “FSD beats Thor.” It is that autonomy is splitting into product categories:

| Autonomy Category | What “Success” Looks Like In 2026 | Who It Favors |

| Supervised consumer driving | Wide rollout, low incident rates, high customer satisfaction | Tesla and OEMs shipping supervised systems |

| Commercial robotaxis | High utilization, safe operations, clear geofenced domains | Waymo-style operators and partnership ecosystems |

| Platform stacks | Repeatable deployment across many vehicle lines | Nvidia-style suppliers and integrators |

What Comes Next: Milestones To Watch In 2026

These signposts will determine whether Nvidia’s Thor platform becomes a true Tesla challenger, or mainly an enabling layer for everyone except Tesla.

- Production rollout of Nvidia-powered supervised city driving

If major OEMs ship and maintain stable performance with strong safety narratives, the “platform can ship” thesis strengthens. - Whether reasoning-based autonomy delivers measurable improvements

The key metric is not marketing language. It is whether intervention rates, serious incidents, and uncomfortable maneuvers decrease meaningfully in real deployments. - Whether sensor fusion becomes the default baseline

If more OEM systems standardize lidar and radar redundancy, the definition of “reasonable safety architecture” shifts. - Regulatory tightening around transparency and incident reporting

More reporting and more scrutiny will favor stacks that can explain behavior, document updates, and demonstrate controlled risk. - The vertical integration rebound

If more OEMs move toward custom compute and deeper in-house autonomy, platform suppliers will need to prove they can still offer differentiation, not just commoditization.

A clear, labeled prediction

Analysts suggest 2026 will mark a shift from “who has the best demo” to “who has the best deployment machine.” The winners will pair strong models with credible safety cases, disciplined reporting, and an economic path to scale. Nvidia is trying to sell that machine. Tesla is trying to be that machine.

Final Thoughts

Huang praising Tesla FSD is the clearest signal yet that the industry’s center of gravity has moved. Autonomy is no longer a debate over whether AI-first driving can work. It is now a debate over who gets to standardize the autonomy stack.

If Nvidia succeeds, Thor becomes the default brain for much of the auto industry, and Tesla’s advantage shifts from capability to brand, fleet learning, and business model execution. If Tesla holds, platforms will still grow, but the market may fragment into “good enough autonomy everywhere” while Tesla pursues the highest ceiling.

Either way, the next chapter is not won with a keynote. It is won in audits, intervention logs, OTA rollouts, and the ability to ship the same capability across millions of vehicles.