In the turbulent first half of the twentieth century—when Bengal’s fields were burdened by debt, its cities humming with colonial ambition, and its people torn between empire and emancipation—one voice roared above the din. A.K. Fazlul Huq, known to generations as Sher-e-Bangla, the Tiger of Bengal, was not born into privilege but into purpose.

Today is his 152nd birth anniversary. He was the rare leader who understood both the language of law and the silence of the peasant, who could speak in the halls of power and still be heard in the paddy fields of Barisal.

Fazlul Huq’s politics was not the politics of slogans—it was the politics of substance. At a time when India’s nationalist movements often revolved around cities and elites, Huq turned the gaze back to the village, to the soil, to the millions who toiled unseen. His vision cut across religion and class, uniting farmers, teachers, and students under one revolutionary idea: that Bengal’s freedom must begin with the freedom of its people.

Today, as Bangladesh continues to wrestle with the balance between development and equality, Sher-e-Bangla’s story stands as both a mirror and a manifesto — a reminder that the most powerful revolutions begin not in parliaments, but in conscience.

Key Milestones at a Glance

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1873 | Born in Barisal | Birth of Bengal’s future reformer |

| 1906 | Joined Indian National Congress | Advocated Hindu–Muslim unity |

| 1929 | Formed Krishak Praja Party | Gave voice to peasants and tenants |

| 1937 | Became Premier of Bengal | First Bengali Muslim Premier |

| 1940 | Proposed Lahore Resolution | Blueprint for Muslim autonomy |

| 1954 | Chief Minister of East Bengal | Championed education and rural justice |

| 1962 | Passed away in Dhaka | The nation mourned the “Tiger of Bengal.” |

Early Life and Education: The Rise of a Scholar from Barisal

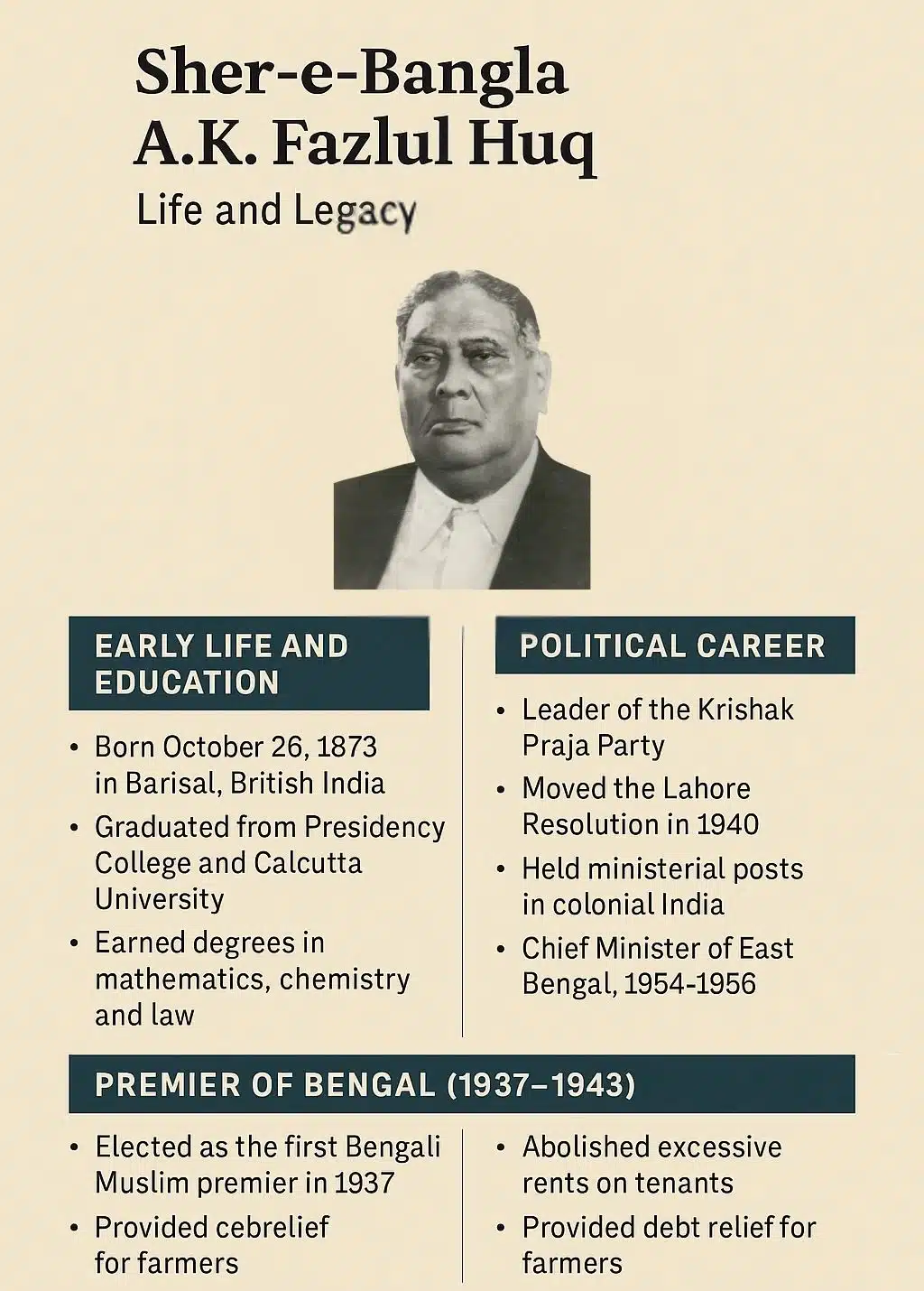

Abul Kasem Fazlul Huq—later revered as Sher-e-Bangla, the “Tiger of Bengal”—was born on October 26, 1873, in a modest Muslim family in Saturia, Barisal, during the height of British colonial rule. His father, Kazi Wazed, was a learned man of integrity who instilled in young Fazlul Huq a sense of discipline and devotion to learning.

From his early days, Huq showed a rare combination of intellect and idealism. After excelling at Barisal Zilla School and Presidency College, he went on to earn degrees in mathematics, chemistry, and law from Calcutta University. His academic brilliance soon landed him a post in the Bengal Civil Service, an achievement rare for Muslims at that time—but his heart lay not in bureaucracy but in public service.

He left the service to pursue law and politics—a decision that would change the course of Bengal’s history.

Early Political Journey: Building Bridges Between Communities

Fazlul Huq entered politics in an era when Bengal was marked by deep divisions—class, religion, and language. Yet, his early work reflected a strong belief in unity and progress through education and social reform.

He joined the Indian National Congress in the early 1900s, where he worked alongside iconic leaders such as Surendranath Banerjee and Chittaranjan Das. As a gifted orator and skilled lawyer, Huq became known for his ability to mobilize both Hindu and Muslim audiences, breaking the stereotype of communal politics that dominated the era.

In 1912, he was appointed Deputy Leader of the Bengal Legislative Council—one of the first Muslims to achieve such status in colonial India. His focus remained on mass education, agrarian justice, and the economic upliftment of Bengal’s rural poor.

The Bengal Pact and the Birth of Peasant Politics

Disillusioned by the Congress’s elitist leadership and its urban bias, Fazlul Huq left the party in the 1920s. He recognized that the real strength of Bengal lay in its villages, where peasants suffered under oppressive zamindars and mounting debt.

To fight for them, he founded the Krishak Praja Party (KPP)—literally the “Farmers’ and Tenants’ Party.”

This was a radical idea in colonial politics: a mass-based peasant movement that prioritized economic rights over communal identity.

Huq’s policies included:

-

Abolishing excessive land rent

-

Reducing rural indebtedness

-

Providing access to education for peasant children

-

Expanding representation for marginalized communities

His movement transformed Bengal’s political landscape, earning him the affectionate title “Banglar Bagh”—the Tiger of Bengal.

Premier of Bengal (1937–1943): Leadership for the Masses

Under the Government of India Act of 1935, Bengal gained limited provincial autonomy, leading to the 1937 elections. Fazlul Huq’s Krishak Praja Party won widespread support, particularly from rural Muslims and lower-income Hindus, allowing him to form a coalition government and become the first Bengali Muslim Premier of Bengal.

As premier, Huq’s government pushed for pro-peasant legislation:

-

The Bengal Tenancy Amendment Act reduced exploitation by landlords.

-

The Debt Settlement Board helped farmers escape lifelong indebtedness.

-

Education reforms—expanded rural schools and scholarships for Muslim students.

However, his tenure was not without challenges. Opposition from powerful landlords, communal agitators, and even within his own coalition tested his political resilience. Yet, his inclusive governance model stood as an early prototype for what we now call people-centric democracy.

The Lahore Resolution (1940): The Birth of a Nation’s Idea

In March 1940, as a senior leader of the All-India Muslim League, Fazlul Huq presented the Lahore Resolution—a historic document that laid the foundation for the creation of Pakistan. The resolution called for the establishment of “independent states” in Muslim-majority areas of India, including Bengal.

While the resolution became a cornerstone of Pakistan’s creation, Huq’s vision was regionalist, not separatist. He envisioned autonomous federations, not a single centralized state—a vision far closer to the later ideals of Bangladesh’s independence.

This nuanced position led to his political fallout with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who feared Huq’s growing popularity and independent streak.

Post-Lahore Years: From Pakistan’s Dream to East Bengal’s Reality

After the Second World War, political tides shifted rapidly. Huq was ousted as premier in 1943 following British-engineered intrigues and communal unrest. Still, his influence endured.

After the Partition of India in 1947, Fazlul Huq became a leading figure in East Pakistan’s provincial politics.

He served as Chief Minister (1954–1956) and later as Governor (1956–1958), continuing his lifelong campaign for education, peasant welfare, and provincial autonomy.

Ironically, the same centralization he warned against in the 1940s became the source of East Pakistan’s grievances under West Pakistani domination—proving the foresight of his federalist ideals.

Vision and Ideology: The People Before Power

A.K. Fazlul Huq’s politics revolved around justice, inclusivity, and self-reliance.

He believed that:

-

A nation’s strength lies in educated citizens, not elites.

-

Religion must not overshadow economic and social reform.

-

True independence means freedom from poverty, ignorance, and inequality.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Huq refused to play the politics of hatred. His rhetoric was fiery, but his purpose was humane. His dream was a Bengal where Muslims and Hindus could coexist in dignity and prosperity.

Legacy: A Bridge Between Bengal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh

Fazlul Huq passed away on April 27, 1962, in Dhaka, leaving behind a towering legacy of leadership and moral integrity.

His name endures in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar—now home to Bangladesh’s National Parliament.

His vision echoes in the agrarian reforms and secular politics that shaped post-1971 Bangladesh.

He is remembered not as a communal leader, but as a statesman of the people—one who fought for education, equity, and dignity long before independence became a reality.

Quotes That Define the Man

“A man’s worth is not in the wealth he owns but in the service he renders to his people.”

— A.K. Fazlul Huq

“The farmer’s sweat is the foundation of our freedom.”

— Speech in Bengal Legislative Assembly, 1938

Takeaways: Why Sher-e-Bangla Still Matters

Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Huq was not just a politician; he was a movement embodied in one man — a force that transcended communal divisions, colonial hierarchies, and political expediency.

In an age where populism often means rhetoric without reform, Huq’s leadership reminds us that true populism uplifts, not divides. His lifelong crusade for the common man, his defiance of both empire and elitism, and his unshakable faith in education make him one of South Asia’s most under-recognized nation-builders.

As Bangladesh continues to balance growth with equality and democracy with inclusion, the roar of the Tiger of Bengal still echoes — not in power, but in principle.