On July 31, 2014, Bengali literature lost one of its most fearless and uncompromising voices. Today, eleven years later, the memory of Nabarun Bhattacharya remains as potent and provocative as ever. A literary rebel, a cultural dissenter, and an architect of the subversive Fyataru universe—Nabarun wasn’t just a writer; he was a movement in himself.

While the world around us leans increasingly toward conformity, curated narratives, and sanitized storytelling, Nabarun’s literature stands as a reminder that words can still sting, revolt, and fly. As we mark his 11th death anniversary, it is time to revisit his radical legacy—a body of work that disrupted polite sensibilities, empowered the marginalized, and questioned everything we take for granted.

Nabarun Bhattacharya: Early Life and Revolutionary Upbringing

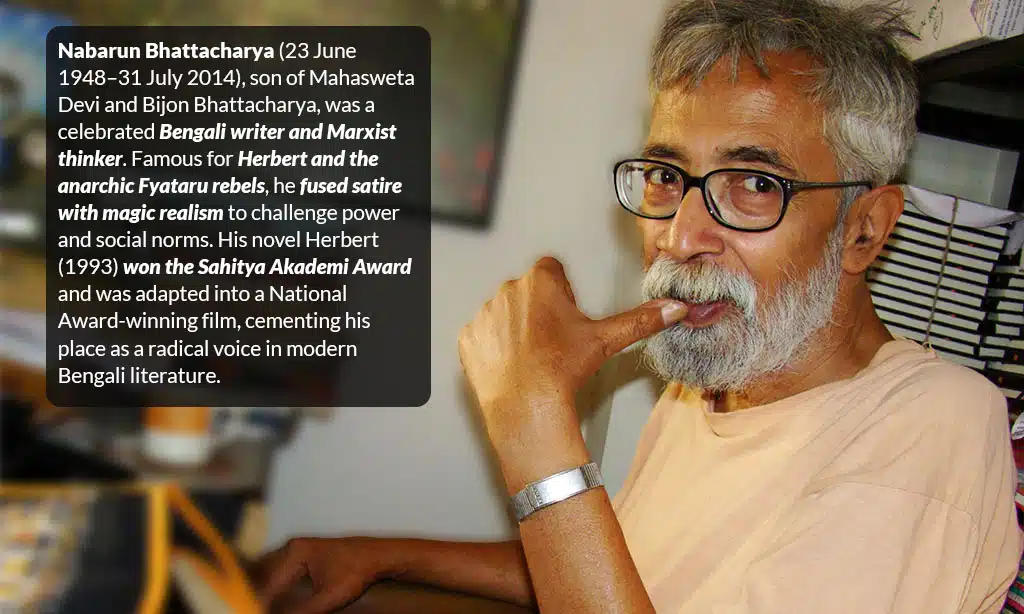

Born on June 23, 1948, in Baharampur, West Bengal, Nabarun Bhattacharya was never destined for a quiet, conventional life. He was born into a family where art, activism, and resistance were not just discussed—they were lived. His father, Bijon Bhattacharya, was a towering figure in Indian theater and one of the founding members of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), while his mother, the legendary Mahashweta Devi, was a prolific writer and a relentless activist for tribal rights.

Growing up amidst rehearsals, political discussions, and protest meetings, young Nabarun absorbed a unique blend of creative energy and political defiance. The family’s intellectual legacy stretched even further: he was the grandson of poet Manish Ghatak and the grand-nephew of acclaimed filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak. In such a household, rebellion wasn’t an option—it was inherited.

Despite this rich cultural lineage, Nabarun carved out his own path. He pursued comparative literature at Jadavpur University, where his exposure to Marxist thought, the European avant-garde, and subaltern theory laid the groundwork for his literary rebellion. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was never content to follow trends—he challenged them head-on.

The Literary Rebel: Style and Substance

From the moment Nabarun Bhattacharya began writing, it was clear he had no intention of following the polite literary traditions of Bengali literature. His voice was jagged, unapologetic, and brimming with fury. Unlike the lyrical elegance of Rabindranath Tagore or the existential subtlety of Jibanananda Das, Nabarun’s prose was visceral—a punch to the gut rather than a whisper to the soul.

His writing was defined by a radical rejection of middle-class complacency and literary elitism. He deliberately infused his language with slang, street dialects, obscenities, and urban grit, breaking away from the refined Bengali idiom. This was not a mere stylistic choice; it was a political one. By using the language of the street, Nabarun centered the lives and voices of those long pushed to the margins of Bengali literature—the jobless, the mad, the anarchists, and the forgotten.

Nabarun wasn’t just a rebel in theme—he was a formalist subverter. He bent genres, mixed poetry with prose, blurred the lines between fantasy and reality, and introduced a surrealism that was both magical and grotesque. His storytelling often felt like a hallucinatory ride through dystopian Kolkata, filled with oddball prophets, bureaucratic absurdities, flying rebels, and anti-heroes who refuse to die quietly.

But beyond the chaos and the satire was a deeply human voice—one that wept for the broken and raged against the system that broke them. His work was less about plot and more about energy, mood, and subversion. It reflected a Kolkata rarely seen in mainstream narratives: one that was angry, decaying, and absurd but still alive with resistance.

As a literary stylist, Nabarun stood alone. He wasn’t interested in awards or recognition. He wrote to disturb, to provoke, and to shake his readers out of their comfort zones. In a world increasingly obsessed with validation and virality, Nabarun’s deliberate obscurity was, in itself, an act of rebellion.

Signature Works That Defined a Generation

Nabarun Bhattacharya’s literary universe is best remembered through his explosive works that carved new dimensions in Bengali literature. At the heart of his writing were characters who resisted, systems that oppressed, and a city that constantly decayed and reinvented itself. His stories weren’t just written—they were launched like grenades into the reader’s consciousness.

Herbert (1993): The Postmodern Prophet of Kolkata

Arguably his most acclaimed work, Herbert introduced readers to Herbert Sarkar, an orphaned eccentric who claims to communicate with the dead. Through this surreal character, Nabarun constructed a complex narrative about urban alienation, bureaucratic cruelty, state violence, and the spiritual emptiness of modernity.

But Herbert wasn’t just a literary figure—he became a symbol of how society pathologizes dissent and dehumanizes the outcast. The novel’s language was laced with absurdity and rebellion, making it an instant classic of postmodern Indian literature. The book won the Sahitya Akademi Award, and in 2005, it was adapted into a critically acclaimed film directed by Suman Mukhopadhyay.

Fyataru Stories: Anarchists with Wings

Among Nabarun’s most iconic creations were the Fyatarus—a gang of winged subaltern anarchists who chant “fyat fyat sh(n)aai sh(n)aai” before taking flight and disrupting the system. These characters—drunk, dirty, brilliant, and free—represent the untameable spirit of resistance.

The Fyatarus are not superheroes. They are anti-heroes. They don’t seek justice—they seek chaos, as a way to shatter the hypocrisy of structured power. Their magical realism wasn’t escapist fantasy; it was political symbolism, where flight meant freedom from caste, class, and control.

Through the Fyatarus, Nabarun achieved what few could—he blended folklore, magic, Marxism, and madness into a sharp-edged political allegory. They remain his most powerful metaphor, immortalized in books, plays, comics, and even films.

Kangal Malshat (War Cry of the Beggars)

If Herbert was his psychological masterwork, Kangal Malshat was his manifesto. This explosive novel brought together a motley crew—Fyatarus, Naxalites, dacoits, and revolutionaries—planning an insurrection against the bourgeoisie. The result was a chaotic, violent, vulgar, and unforgettable ride through class war, revolution, and urban apocalypse.

The book was adapted into a controversial film in 2013 that faced criticism for its violent visuals and was initially denied certification. But that only further proved Nabarun’s point—real rebellion cannot be domesticated.

Other Notable Works

-

Lubdhak: A novel of philosophical depth and metaphysical inquiry.

-

Ei Mrityu Upotyoka Aamar Desh Na (“This Valley of Death Is Not My Country”): A title that has come to define Nabarun’s politics of hope and resistance.

-

Andho Biral, Mobloge Novel, Mahajaaner Aayna—works that continued to explore urban decay, absurdity, and rebellion.

Each of these works may vary in form and theme, but together they created an ecosystem of revolt—a genre Nabarun built with his own rules and set ablaze with his own fire.

Political Consciousness and Radicalism

Nabarun Bhattacharya was not just a writer of rebellion—he lived and breathed political defiance. He didn’t write to entertain or to earn accolades; he wrote to agitate, to awaken, and to hold power accountable. His literature was a battlefield, and every page was a confrontation with the complacency of society.

Unlike many so-called “progressive” voices who operated within comfortable ideological silos, Nabarun rejected both capitalist consumerism and Stalinist orthodoxy. He believed that true resistance required the courage to critique all forms of power—whether it came from corporate boardrooms or from authoritarian leftist parties. This made him both feared and revered in literary and political circles.

He frequently targeted what he called the “bhadralok hypocrisy”—the Bengali urban middle class that cloaked its privilege in intellectualism but remained apathetic to real injustice. In his eyes, liberal elitism was just another form of violence, especially when it turned a blind eye to the lives of workers, hawkers, beggars, and anarchists.

Through characters like Herbert and the Fyatarus, Nabarun exposed the ways in which the state silences dissent—through psychiatry, through propaganda, and through brute force. In Herbert, the protagonist is declared mentally ill for refusing to conform. In the Fyataru tales, state machinery becomes a grotesque joke, unable to contain even a small group of flying misfits.

But his rebellion was not abstract. Nabarun wrote from the wounds of a decaying city. Post-Naxalite disillusionment, communal tensions, neoliberal exploitation, and the hollow promises of left governance in West Bengal formed the backdrop of his stories. Yet, he never gave in to despair. His anger was not cynical—it was constructive, ferocious, and urgent.

He often described his work as “jangalmahaler sahitya”—literature from the jungle, from the margins, where resistance was not poetic but desperate, dirty, and dangerous.

In an age where political correctness is often mistaken for progress, Nabarun reminds us that real politics in literature means risk—the risk of offending, of alienating, and of refusing to play safe.

Nabarun in Cinema and Popular Culture

Although Nabarun Bhattacharya was fiercely protective of the written word, his imaginative worlds were far too powerful to remain confined to the page. His stories—dark, surreal, rebellious—naturally attracted filmmakers, illustrators, and underground artists who were drawn to his unique blend of realism and radicalism. Over time, his work began to spill into cinema, theater, and visual culture, extending his legacy far beyond literary circles.

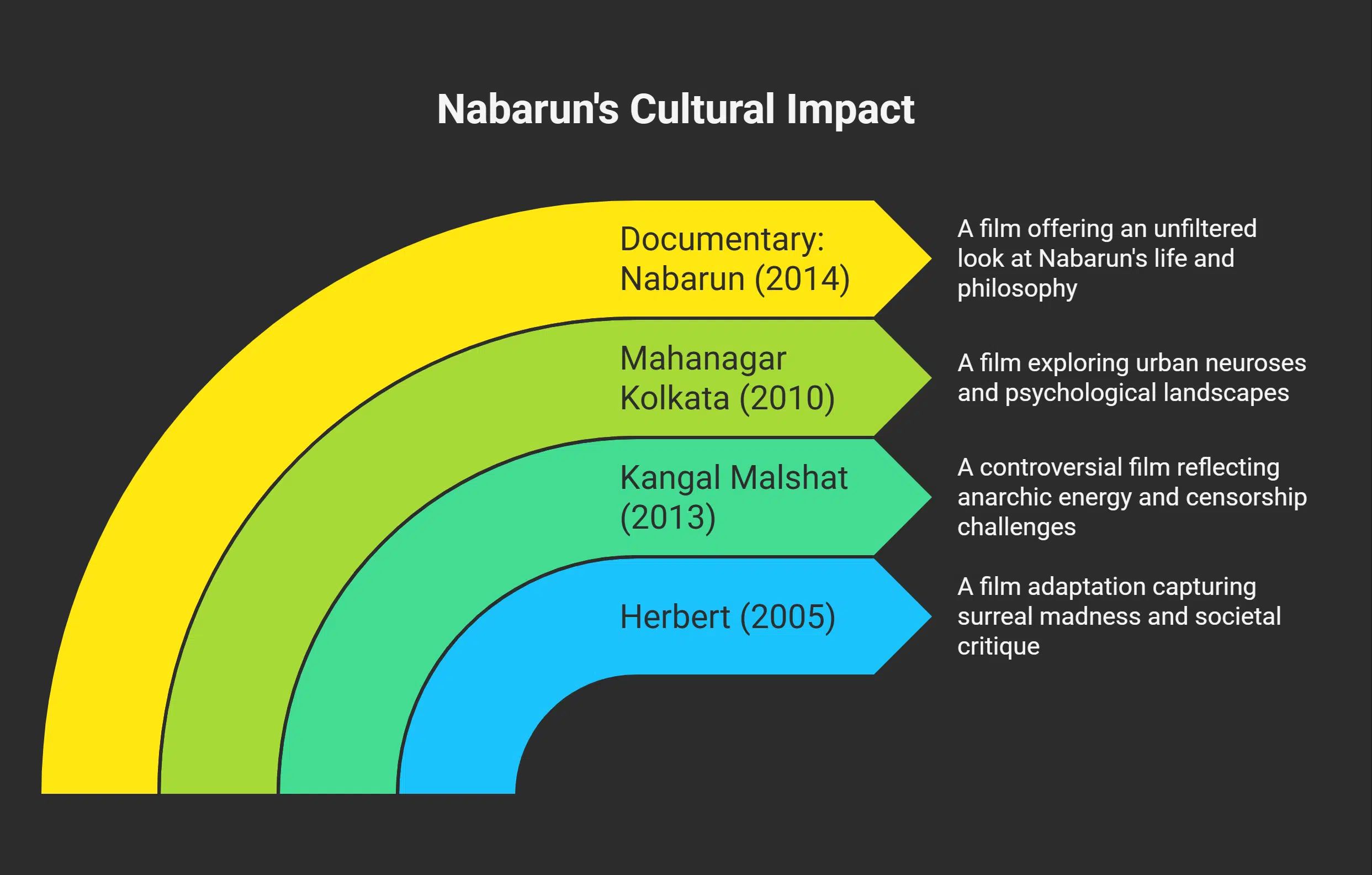

Herbert (2005): Cinema Meets the Psychedelic Prophet

Director Suman Mukhopadhyay’s adaptation of Herbert brought the novel’s surreal madness to life in all its chaotic brilliance. Using disorienting visuals, experimental editing, and philosophical undertones, the film captured the inner turmoil of Herbert Sarkar—part prophet, part outcast, and fully revolutionary.

The film was widely praised, screened at international festivals, and introduced a new generation to Nabarun’s haunting vision of Kolkata—a city bursting with ghosts, corruption, and forgotten lives. More than a story, it felt like a wake-up call.

Kangal Malshat (2013): The Celluloid Riot

Arguably the most controversial adaptation of Nabarun’s work, Kangal Malshat was also directed by Mukhopadhyay. It was a cinematic attempt to capture the book’s anarchic energy, featuring Fyatarus, revolutionaries, talking birds, and explosive dialogues. The visuals were violent, psychedelic, and unapologetically grotesque—just like the book.

But the film ran into trouble with India’s Central Board of Film Certification, which delayed its release and demanded cuts, labeling it “anti-establishment.” Nabarun was openly critical of the censorship, defending the director’s vision and reaffirming his belief that art must never be filtered for comfort.

Despite mixed critical reception, the film achieved cult status—especially among students and radical thinkers who saw it as a call to arms.

Mahanagar Kolkata (2010): The City of Dissent

This lesser-known but powerful film adapted three of Nabarun’s short stories, exploring the neuroses and nightmares of urban existence. It wasn’t as explosive as Kangal Malshat, but it offered a quieter, more psychological look into the mindscapes of his characters.

Documentary: Nabarun (2014)

Shortly before his death, indie filmmaker Q (Qaushiq Mukherjee)—known for his experimental films—created a documentary simply titled Nabarun. It offered an unfiltered look at the man behind the madness, blending interviews, performance art, street scenes, and voiceovers.

The film captured Nabarun’s discomfort with fame, his fierce independence, and his absolute refusal to become a literary celebrity. It was less biography, more invocation—a portrait of a mind that could not be tamed.

His Intellectual Legacy: Why Nabarun Still Matters

More than a decade after his passing, Nabarun Bhattacharya’s words still burn with relevance. His literature didn’t belong to a specific political party, generation, or ideology—it belonged to those who dared to question, to rage, and to imagine a different world. That is why he continues to matter.

In today’s world of digital surveillance, algorithmic conformity, and commodified resistance, Nabarun’s work feels eerily prophetic. His characters—especially the Fyatarus—embody a kind of anarchic freedom that is nearly extinct today. In an age where rebellion is often turned into branding, Nabarun reminds us that real dissent cannot be sponsored or sanitized.

He gave voice to those who were invisible in literature—the mentally ill, the destitute, the jobless, the street hawkers, the dreamers. In doing so, he radically expanded the idea of who could be a literary protagonist. His language rejected polish for power, clarity for chaos, and elegance for urgency.

For younger writers and thinkers, Nabarun remains a beacon of uncompromising courage. His refusal to sell out, to soften his politics, or to dilute his art makes him an icon of literary honesty. At a time when many writers toe the line for publication or prestige, Nabarun’s entire career stands as an act of refusal.

Academically, his works have been increasingly studied through the lenses of postcolonialism, subaltern studies, magical realism, and urban anthropology. Universities across India and abroad include Herbert and the Fyataru tales in syllabi exploring counterculture literature, resistance theory, and dystopian narratives.

Perhaps most importantly, his legacy survives in the voices he inspired—writers, filmmakers, poets, and activists who refuse to conform. Whether in a campus protest poster, an underground street play, or a self-published zine quoting his lines, Nabarun lives on as a cultural insurgent who taught us that literature could still fight back.

Takeaways: The Pen Still Flies

Nabarun Bhattacharya didn’t believe in literature as decoration. He believed in it as detonation. His pen wasn’t dipped in ink—it was soaked in defiance. Even now, eleven years after his death, his words remain weapons, his characters still resist, and his ideas continue to fly, unchained by time.

In a world increasingly obsessed with perfection, politeness, and profit, Nabarun’s unfiltered rage feels like oxygen. His Fyatarus still haunt the skies of Kolkata and the imaginations of readers who refuse to be tamed. Herbert still whispers warnings about madness, state violence, and lost innocence. And his essays and editorials still scream from the margins, demanding to be heard.

Nabarun taught us that writing could disturb instead of please, challenge instead of comfort, and provoke instead of pacify. And for that, he remains irreplaceable.

So, on this 11th death anniversary, let us not mourn quietly. Let us shout, let us read him aloud, let us write dangerously. Let us remember that somewhere, high above the city, the Fyatarus are still flying—fyat fyat sh(n)aai sh(n)aai—and the rebel with a pen is still writing through us all.