The UK’s UK Sovereign AI Compute push and its £500m public-sector compute pledge matter now because AI advantage is shifting from ideas to infrastructure. Whoever controls scarce compute can set priorities, protect sensitive services, and shape the domestic AI market while the grid, chips, and cloud giants tighten the bottleneck.

From AI Ambition To Compute Reality

For years, the UK sold its AI story through research strength, start-up energy, and a reputation for pragmatic regulation. Then the economics of modern AI caught up with the politics. Training and running advanced models stopped looking like “software you download” and started looking like heavy industry: expensive chips, specialized data centres, long lead times, and electricity supply that has to be planned years in advance.

That is the context in which the headline pledge took on weight. When Rishi Sunak’s government signaled £500 million for AI compute aimed at public-sector and research capability, it was not just a funding line. It was an admission that the UK’s AI competitiveness depends on access to “factory floor” capacity that markets may not allocate to universities, start-ups, or public services when demand spikes.

The UK’s compute shortage has always been a structural issue, not a temporary inconvenience. Academic labs and smaller companies rarely compete with hyperscalers and frontier firms for the newest GPUs. Even when they can afford them, procurement cycles, compliance requirements, and the lack of secure environments slow adoption. This gap matters because public-interest innovation often starts outside the big platforms: in universities, small applied AI teams, and mission-driven work that does not monetize quickly enough to win scarce cloud capacity.

So the UK pivoted from “we will regulate and adopt AI” to “we must also secure the inputs that make AI possible.” That is why compute moved to the heart of strategy documents and delivery units. It also explains why the phrase “sovereign AI” gained momentum, even though the UK is not trying to build an autarkic system.

Two political dynamics accelerated the shift.

- The competition narrative changed. The UK began framing AI less as a tech sector story and more as a national productivity and security story. When a government claims AI can lift productivity, it also implicitly claims AI access must not become an external dependency that can be priced, throttled, or geopolitically constrained.

- The policy pendulum swung from safety diplomacy to growth delivery. The UK’s earlier global posture emphasized AI safety convening and governance leadership. The later posture emphasizes “making AI work” for the public sector and the economy, which requires compute, talent, and infrastructure, not just rules.

This evolution is visible in how the UK describes its own goals. The focus moved toward building a public compute base, attracting private data centre investment, and using procurement to modernize services at scale. In that framing, £500m is not meant to “win the arms race” outright. It is meant to ensure the UK stays in the game and keeps enough leverage to decide where and how AI shows up in government.

Here is the key strategic reframing in one line: the UK now treats compute like critical infrastructure, not like a discretionary IT spend.

| UK Policy Shift | What The UK Said Before | What The UK Is Saying Now | Why The Change Matters |

| AI as capability | “We have world-class research and a strong ecosystem” | “We need compute, power, and delivery capacity to convert research into advantage” | Infrastructure decides who can build and deploy at speed |

| AI as governance | “We can lead on safety and regulation” | “We must pair governance with domestic capability and public-sector adoption” | You cannot govern what you cannot operationalize |

| AI as market outcome | “Industry will invest, government will enable” | “Government must also own or allocate a portion of compute” | Allocation power becomes a national lever |

The deeper point is historical. In previous technology cycles, states focused on roads, ports, and power grids, then let private firms innovate on top. In this cycle, the “road system” for AI includes high-end compute and secure environments. Without those, the UK risks becoming a consumer of other countries’ models rather than a serious producer of frontier and applied capability.

What UK Sovereign AI Compute Actually Means?

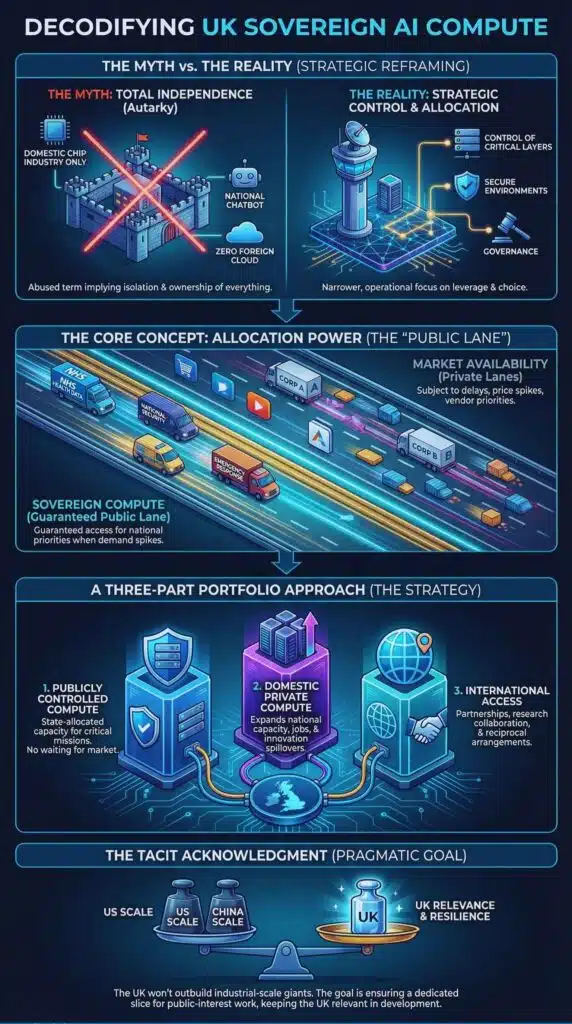

“Sovereign AI” can mean many things, and the term often gets abused. Some people hear it and imagine a national chatbot, a domestic chip industry, and complete independence from foreign clouds. The UK’s version is narrower and more operational. It focuses on control and allocation rather than total ownership.

At its core, UK Sovereign AI Compute means the public sector has enough compute that it can allocate quickly to national priorities without waiting for market availability, procurement delays, or vendor priorities. That is a subtle but important difference. The UK is not claiming it will own all compute needed for the economy. It is saying it wants a public lane that stays available when the private lane gets crowded.

Think of the UK compute strategy as a three-part portfolio:

- Publicly controlled compute that the state can allocate to critical missions.

- Domestic private compute that expands national capacity, jobs, and innovation spillovers.

- International compute access through partnerships, research collaboration, and reciprocal arrangements.

This portfolio approach is a tacit acknowledgment of reality. The UK will not outbuild the United States or match China’s industrial-scale investment in AI infrastructure. The UK can, however, ensure that a slice of compute is dedicated to public-interest work and resilience, and that domestic capacity grows enough to keep the UK relevant in model development and deployment.

Why allocation power is the real prize?

In a compute-constrained world, the most strategic asset is not a single supercomputer. It is the ability to decide who gets time on it, for what purpose, under what security model, and with what accountability. Allocation turns compute into policy.

That matters for five reasons.

- Critical services cannot rely on “best effort” capacity. Health, welfare, emergency response, and national security workloads need guaranteed availability and predictable governance. When compute runs short, vendors prioritize their biggest customers and highest-margin use cases. Governments cannot assume they sit at the top of that list.

- Sensitive workloads need controlled environments. Even when cloud security is strong, the public sector often needs strict data-handling models, audit trails, and contractual clarity. Sovereign compute does not automatically solve privacy and accountability, but it can make governance easier when workloads stay inside dedicated environments.

- Public compute can reduce lock-in over time. If the public sector builds its AI workflows entirely around a single vendor’s managed services, it becomes hard to switch without rewriting systems and retraining staff. A public compute layer can encourage portability and multi-vendor competition, especially if it supports multiple architectures and open tooling.

- It changes bargaining power with frontier firms. If the UK can allocate compute and offers a pathway for applied research and evaluation at scale, it can negotiate partnerships from a position of more agency. The UK becomes more than a buyer. It becomes a platform for testing, deployment, and mission-driven scaling.

- It signals seriousness to investors. Data centres, energy developers, and chip supply chains follow credible policy signals. A £500m pledge and a dedicated delivery unit are meant to say, “This is not a one-off press release. We are building an ecosystem.”

The sovereignty paradox

There is a paradox here. Even sovereign compute can depend on foreign technology, especially GPUs and advanced chips. That does not make the project pointless. It simply shifts the sovereignty goal from “own everything” to “control enough of the stack to make independent choices.”

The UK can improve sovereignty without claiming full independence by pursuing:

- Diverse hardware procurement and benchmarking to avoid a single-vendor trap

- Open standards and portability requirements in public-sector AI deployments

- A strong public compute access model for research, evaluation, and public service pilots

- Clear governance that defines what must be sovereign and what can remain commercial

This is not just semantics. It determines whether “sovereign AI” becomes a durable industrial policy or a slogan that collapses under the realities of the global supply chain.

| Three Ways To Interpret “Sovereign AI” | What It Implies | What It Costs | UK-Style Practical Version |

| Total independence | Domestic chips, clouds, models, and data | Extremely expensive and slow | Not realistic in the near term |

| Control of critical layers | Compute allocation, secure environments, governance | High but manageable | The UK’s core direction |

| Influence through partnerships | Access to frontier tech via alliances | Dependence risk | Works only if UK retains leverage |

The UK’s strategy sits in the middle. It aims for control where it matters, and partnerships where scale is needed.

The Real Constraints: Money, Chips, Power, And Time

The hardest part of the UK’s sovereign compute push is not writing the policy. It is delivering in a world where AI infrastructure collides with energy systems, planning rules, and a tight global chip supply.

The money problem is not just “how much,” it is “how long”

A one-time pledge can build a flagship. A decade-long commitment builds a capability. AI infrastructure demands recurring investment: hardware refresh cycles, operations teams, security, cooling upgrades, and software maintenance. Compute becomes obsolete faster than most public assets. That creates a governance challenge for government budgets that prefer capital projects with clear endpoints.

The £500m figure matters because it is big enough to establish credibility, but it also creates a risk. If leaders treat it as a complete solution, the UK ends up with a public compute base that feels impressive on launch day but fails to keep pace with the frontier within a few years.

The correct interpretation is this: £500m is a down payment on a long game.

The chip bottleneck is a strategic dependency

Even if the UK builds more data centres, it still needs chips. High-end AI chips remain constrained by a global supply chain dominated by a small set of firms and manufacturing nodes. This is why sovereign AI debates often converge on semiconductors, export controls, and industrial alliances.

The UK is unlikely to build a full domestic advanced chip manufacturing base in the near term. So the practical path is to secure reliable access through procurement, alliances, and a policy environment that makes the UK a preferred destination for deployment and R&D.

Power and grid connections are the hidden governor on growth

Compute scales only as fast as energy supply and grid access allow. Data centres draw large, continuous loads. The UK’s own grid analyses show that data centre demand already represents a meaningful share of electricity consumption and could rise substantially over the next decade.

This is why policy discussion increasingly includes:

- Locating new capacity near available grid headroom

- Fast-tracking permitting in designated growth zones

- Aligning data centre build-out with clean power generation

- Planning for water use and heat management to reduce local resistance

The political risk is that AI infrastructure becomes controversial at the local level, especially if communities associate data centres with land use, water consumption, and limited local benefits.

A clear picture of the infrastructure trajectory

The following figures capture the shape of the challenge and why the UK is moving to a “zones and grid” mindset.

| UK Data Centre And Electricity Snapshot | Current Baseline | What It Suggests For Policy |

| Number of data centres | About 523 as of early 2025 | The UK already hosts a large footprint, but growth stresses local infrastructure |

| Electricity use | About 7.6 TWh in 2024, around 2% of GB electricity demand | AI growth turns power planning into AI policy |

| Future consumption scenarios | Roughly 20 to 41 TWh by 2035 in published scenario ranges | The UK must treat data centres like a major new demand sector |

If the UK wants “sovereign compute,” it must solve the boring problems: grid upgrades, land availability, and the time it takes to connect high-load users. In practice, energy timelines can outlast electoral cycles. That is why the UK keeps returning to the idea of a delivery unit that can maintain continuity.

Winners and losers are already emerging

Compute policy redistributes advantage inside the economy. It changes which sectors get cheaper experimentation, which companies gain procurement pathways, and which regions attract investment.

| Likely Winners | Why | Likely Losers | Why |

| Research universities and public labs | Improved access to scarce compute, easier evaluation at scale | Smaller AI labs without access routes | The gap widens if access processes become bureaucratic |

| UK AI start-ups building public-sector products | Procurement and compute access can reduce early costs | Firms dependent on a single hyperscaler stack | Lock-in raises switching costs and strategic risk |

| Regions with grid headroom and supportive planning | Faster siting and connections attract data centres | Regions with congested grid and restrictive planning | Investment bypasses them, deepening regional gaps |

| Public services with clear, bounded AI use cases | Ability to pilot safely and scale responsibly | Services lacking data readiness | Compute alone cannot fix messy data and weak governance |

A sober analysis has to admit that compute investment alone will not deliver productivity gains. The UK must also address data quality, service redesign, staff capability, and accountability. Compute is a necessary condition for modern AI, not a sufficient one.

Partnerships, Politics, And The Governance Test

The UK’s sovereign compute push sits alongside partnerships with major AI firms and a rising wave of public-sector AI procurement. This is where the strategy becomes politically delicate.

Partnerships can increase capability, or deepen dependence

The UK has signaled partnerships with frontier firms as part of its wider AI growth agenda. That can deliver faster access to models, tooling, and expertise, especially in areas like public sector modernization and secure deployment.

But partnerships also create two risks:

- Dependency risk: Public services may build workflows that rely on specific vendors’ models and interfaces.

- Policy capture risk: Vendors shape standards, procurement norms, and technical architectures in ways that entrench their position.

The “sovereign” answer is not to reject partnerships. It is to structure them with conditions that preserve agency. For example:

- Require interoperability and exportable logs for auditing

- Maintain model evaluation and red-teaming capacity inside public compute environments

- Separate sensitive workloads from vendor-managed black boxes where possible

- Build internal capability so the public sector remains an informed buyer, not a passive client

The procurement surge is an industrial policy, whether acknowledged or not

When government departments buy AI at scale, they shape the domestic market. They decide which vendors become default suppliers, which compliance models become standard, and which problem categories get automated first.

This is why governance matters as much as compute. If procurement accelerates without strong accountability, the UK risks backlash. Public trust becomes the limiting factor. The first major scandal linked to automated decisions or poorly deployed AI systems can freeze momentum for years, regardless of compute capacity.

So sovereign compute should include governance guardrails that make adoption more defensible, such as:

- Transparent evaluation standards for models used in sensitive contexts

- Clear documentation of decision boundaries, human oversight, and appeals processes

- Independent audit capability and red-team testing for high-risk deployments

- Data governance reforms that improve quality and traceability

The European and global context is intensifying

The UK’s sovereign AI posture is also a response to what peers are doing. Across Europe, governments are building shared compute ecosystems and national champions. Some countries are explicitly tying sovereignty to defence applications and domestic hosting. Others are using sovereignty language to attract massive private investment in data centres and industrial AI platforms.

This global trend matters for the UK because:

- Competition for chips and power is international. Investors and suppliers choose jurisdictions that offer speed and certainty.

- Standards will harden. Procurement, security, and compliance models in large blocs influence global defaults.

- Talent follows infrastructure. Researchers and engineers go where they can run experiments and ship products at scale.

In that environment, the UK’s sovereign compute project becomes a credibility signal. If the UK can demonstrate reliable compute access for research and public sector missions, it stays attractive to talent and investment. If it cannot, the UK risks a slow drift into being primarily a deployment market for other nations’ models.

Key statistics that frame the governance question

- Cloud infrastructure spending remains heavily concentrated among a small number of global providers, which increases systemic dependency risk.

- Public-sector AI procurement is rising, which can accelerate modernization but also magnifies accountability failures.

- Data centre electricity demand is climbing, pulling AI into the center of energy policy and net-zero debates.

The underlying message is simple: The UK can only sell sovereign AI politically if it pairs compute with credible governance and visible public value.

What Happens Next: Milestones, Watchpoints, And Scenarios?

The UK’s sovereign compute ambition will not be decided by one announcement. It will be decided by a chain of delivery milestones that reveal whether the UK can turn a funding pledge into a durable capability.

Milestones that matter in 2026 and beyond

- Public compute access and allocation rules

The UK must show that researchers, start-ups, and public sector teams can access compute through clear pathways that reward mission value and technical readiness, not just institutional familiarity. If allocation becomes opaque or slow, demand will route back to hyperscalers and the “sovereign lane” will lose legitimacy.

- Scale-up plans for public compute

Hardware builds headlines, but refresh cycles define capability. The UK’s next decisions about upgrading systems, expanding capacity, and supporting multiple architectures will determine whether public compute remains useful for frontier-adjacent work or becomes limited to smaller models and inference tasks.

- Energy and siting outcomes

If growth zones and planning reforms speed connections, the UK will attract private investment and expand domestic compute. If grid bottlenecks persist, the UK will struggle to convert ambition into capacity, and £500m will feel like a drop in a rising tide.

- Public sector adoption outcomes

The success metric will not be teraflops. It will be measurable improvements in public services: reduced waiting times, better triage, improved fraud detection, faster casework, improved citizen-facing interfaces, and higher staff productivity without reducing accountability.

Three plausible futures, clearly labeled

Base-case scenario

The UK builds a credible public compute lane, improves access for research and mission pilots, and attracts some private data centre investment. The UK remains behind US-China frontier scale, but stays globally relevant and develops strong applied AI capability in public services and regulated sectors.

Optimistic scenario

The UK establishes sustained funding and a predictable upgrade cycle, aligns energy planning with data centre growth, and builds a robust governance model that earns public trust. The UK becomes a preferred European hub for secure AI deployment, evaluation, and mission-driven innovation, with partnerships structured to preserve national agency.

Downside scenario

Grid constraints and planning delays slow domestic build-out. Public compute becomes underutilized or captured by a narrow set of users. Partnerships deepen dependence, procurement fragments across departments, and one or two high-profile governance failures trigger a political backlash that stalls adoption.

What to watch, in plain terms?

| Watchpoint | Why It Matters | What “Good” Looks Like |

| Compute allocation transparency | Determines whether sovereign compute serves national priorities | Clear criteria, predictable timelines, published outcomes |

| Hardware refresh cycle | Prevents capability decay | Planned upgrades, multi-year commitments, diversified procurement |

| Grid connection timelines | Controls how fast domestic compute grows | Faster approvals, zones with power certainty, cleaner energy alignment |

| Public trust signals | Determines whether AI adoption can scale | Audits, oversight, documented safeguards, visible public benefit |

The UK Sovereign AI Compute push is best understood as an attempt to regain leverage in a world where compute has become the bottleneck of progress. The £500m pledge matters because it signals the state will not rely purely on market allocation for a resource that now underpins public services, national security, and productivity growth.

But the pledge only becomes “sovereignty” if the UK can do three things at once: build and refresh capability over time, unlock energy and siting execution, and govern public-sector AI in a way that earns trust. If the UK manages that balance, it will not need to outspend bigger powers to stay competitive. It will need to out-deliver them in targeted missions and credible governance.