The Arctic’s melting ice is no longer only an environmental warning. It is now the opening act of a high-stakes geopolitical contest, where states compete to shape access, rules, and long-term advantage. In early 2026, Arctic sovereignty resource control has become a defining issue because it links climate reality with defense planning, critical minerals, shipping routes, and alliance politics.

For most of modern history, the Arctic’s harsh conditions acted like a natural barrier. Ice, darkness, and distance kept competition limited and expensive. That barrier is thinning, and not just physically. Decision-makers now treat the High North as a place where economic security and national security overlap, often in the same project, the same port, and the same satellite footprint.

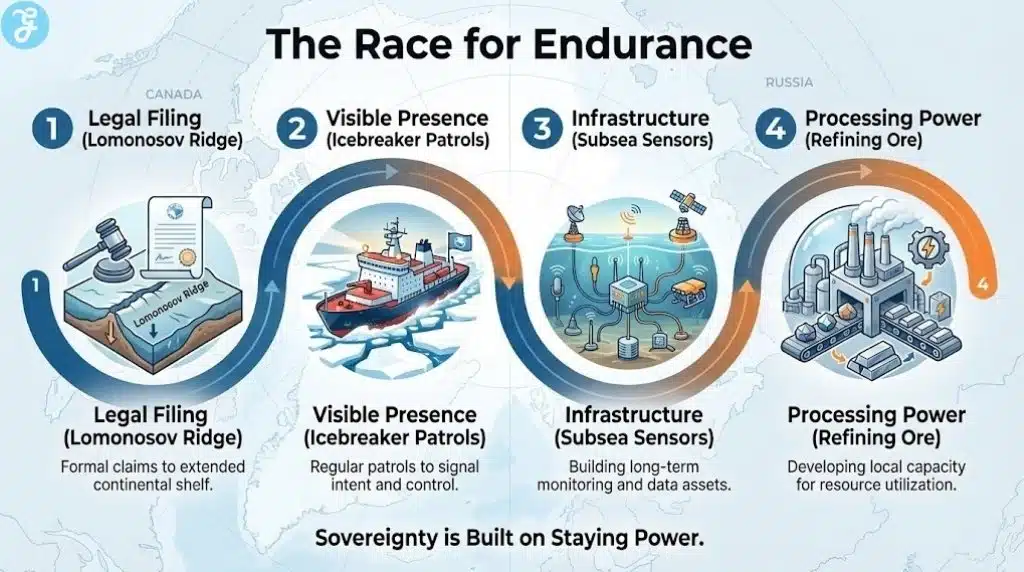

This is not a simple land grab. It is a multi-layered race to secure presence, enforce claims, and build the infrastructure needed to stay. The winners will not be the first to arrive. They will be the ones who can operate year after year, protect assets in extreme conditions, and keep partners aligned under political pressure.

The Arctic’s New Strategic Value

The Arctic’s strategic value comes from three forces moving at once. The first is access. Reduced sea ice and longer navigable seasons lower the barrier to shipping, surveying, and construction. The second is scarcity anxiety. Energy markets, critical minerals, and supply chain shocks have pushed governments to seek alternate sources and alternate routes. The third is deterrence logic. Northern approaches matter more as missile technology evolves and as surveillance, early warning, and space-based systems become central to defense.

The Arctic is also becoming important because it offers leverage without requiring global dominance. A state that can shape Arctic rules and logistics can influence trade patterns, resource flows, and security posture across the North Atlantic and the North Pacific. That makes the region attractive even for actors that are not Arctic littoral states.

Still, the environment remains unforgiving. The Arctic punishes weak planning and thin infrastructure. Fog, ice variability, limited ports, and search-and-rescue gaps create costs that do not exist on southern routes. This tension between strategic desire and operational difficulty is part of what fuels the competition. States push forward because the long-term prize looks large, even if the near-term economics remain uncertain.

From Cooperative Era To Contested Era

For decades, many leaders described the Arctic as a zone of practical cooperation. Science, environmental monitoring, and regional diplomacy created a sense that rivalry could be managed. That model weakened as global tensions rose in the 2020s and spilled into Arctic governance.

In early 2026, the region feels more security-first. Military exercises, surveillance patterns, and alliance planning carry more weight than consensus-driven diplomacy. Commercial decisions are increasingly filtered through security policy, especially when infrastructure can be dual-use or when minerals have defense applications.

This shift changes how Arctic states behave. They invest in presence, patrol capacity, and legal positioning. They also move faster on strategic infrastructure like sensors, airfields, ports, and subsea connectivity. Even when these actions do not decide legal ownership, they shape bargaining power and deterrence.

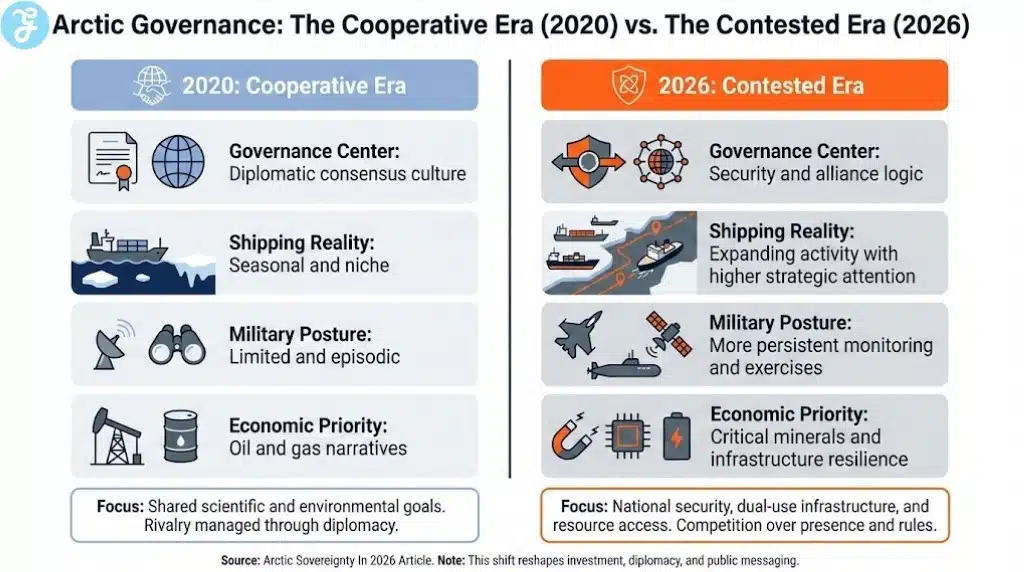

A simple way to capture the change is to compare what defined the two eras.

| Strategic Pillar | Earlier Pattern | Early 2026 Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Governance Center | Diplomatic consensus culture | Security and alliance logic |

| Shipping Reality | Seasonal and niche | Expanding activity with higher strategic attention |

| Military Posture | Limited and episodic | More persistent monitoring and exercises |

| Economic Priority | Oil and gas narratives | Critical minerals and infrastructure resilience |

The Arctic has not become a full-time battlefield, but it has become a place where states plan for that possibility. That alone reshapes investment, diplomacy, and public messaging.

Arctic Sovereignty Resource Control And The Legal Contest

The legal arena remains a core part of the race. Much of the Arctic is governed through the rules of the sea, especially Exclusive Economic Zones. Those zones are broadly defined and well understood. The harder fight sits beyond the standard zones, where states pursue extended continental shelf claims and where undersea features become politically meaningful.

This is where disputes become technical and slow. States submit evidence, panels review it, and the process can take years. Overlapping interests around features like the Lomonosov Ridge illustrate why the legal contest matters. If a claim is accepted and later negotiated into a settlement, it can shape who gains rights to seabed resources over huge areas.

The slowdown creates incentives for visible presence. When law takes time, states signal intent through icebreaker patrols, research missions, infrastructure investment, and economic activity. These actions do not automatically create ownership, but they can create momentum. They also create facts that become harder to ignore during negotiations.

A second legal tension involves internal-waters claims and transit rights. The Arctic’s major passages are not just shipping lanes. They are sovereignty arguments. Every ship that transits becomes a political data point, especially when states disagree about whether a route counts as internal waters or an international strait.

The net effect is that the Arctic’s legal framework is stable in principle but stressed in practice. It offers tools for claims and restraint, yet it cannot prevent power politics. It can only shape the form that power politics takes.

Greenland And The Security Geography Of The North Atlantic

Greenland sits at the center of Arctic strategic geography. It lies between North America and Europe, which makes it valuable for early warning, tracking, and access. It also sits near routes that matter for naval movement and for the protection of northern infrastructure.

In early 2026, Greenland’s role is increasingly framed through national security. The region is discussed in the same breath as missile defense, hypersonic threats, and alliance coverage. Even when political rhetoric fluctuates, the direction of policy is clear. Northern infrastructure and northern access are being treated as core elements of deterrence.

This has several consequences. First, it increases military interest in basing rights, airfields, and sensor networks. Second, it increases scrutiny over investment, especially in infrastructure that can support logistics, communications, or surveillance. Third, it pulls Greenland into broader alliance politics, where sovereignty sensitivities are high and where domestic politics in multiple countries can constrain deals.

The most important point is that Greenland is not simply a strategic object. Its local politics and development choices matter. Resource extraction and infrastructure can bring jobs and revenue, but they also bring environmental risk and concerns over foreign influence. That tension shapes what kind of projects can proceed, how fast they can proceed, and which partners are acceptable.

For the wider Arctic contest, Greenland becomes a test case. It tests whether allies can expand security posture without triggering sovereignty backlash. It also tests whether mineral development can proceed under tight security screening while still delivering local economic value.

Russia’s Arctic Posture And The Militarization Cycle

Russia’s Arctic presence matters because of scale. It holds a large share of the Arctic coastline and has long treated the region as strategically vital. Its posture includes military infrastructure, patrol capability, and a strong interest in regulating and benefiting from northern shipping activity.

The Arctic’s military significance is not only about ground forces. It is about air and maritime approaches, undersea awareness, and the ability to protect or threaten infrastructure like ports, energy sites, and communication lines. The Arctic also sits under key flight paths and surveillance arcs, which makes it relevant for early warning and response planning.

This creates a militarization cycle. When one actor builds capacity, others interpret it as long-term intent. They respond with their own capabilities, often in the name of deterrence and resilience. Exercises become larger, monitoring becomes more constant, and the risk of miscalculation rises.

The Arctic also invites gray-zone pressure. Remote infrastructure can be targeted in ways that are hard to attribute quickly. Cyber incidents, cable disruptions, and staged maritime events can test response thresholds without crossing into open conflict. In a region where response times are long and conditions are harsh, small disruptions can have outsized impact.

This is why Arctic security planning increasingly focuses on endurance and repair capacity. The ability to restore a port, fix a cable, or maintain an airfield through winter conditions can be as important as the ability to deploy new assets.

China’s Arctic Strategy And The Investment Backlash

China’s Arctic approach blends science, commerce, and long-term positioning. It wants access to routes that reduce reliance on vulnerable chokepoints. It also wants options in minerals and energy that can support long-term industrial goals. Even when Arctic shipping is not yet a mainstream solution for global container trade, it functions as a strategic hedge.

At the same time, Western governments and Arctic actors increasingly treat Chinese investment as a security question, not just a financial one. That matters because Arctic infrastructure is often dual-use. A port is a port, but it can also support surveillance, logistics, and military operations. A research footprint can be purely scientific, but it can also expand knowledge and presence in a sensitive region.

This dynamic pushes the Arctic toward economic partition. Trusted-partner frameworks grow stronger. Investment screening becomes tighter. Projects with strategic implications become harder to fund unless they align with security expectations.

The risk is that economic partition hardens rivalry. When one bloc restricts access, the other bloc looks for alternate pathways and builds parallel systems. Over time, that can increase competition over the same physical space, even when economic logic would prefer cooperation.

In early 2026, this trend adds a new layer to the sovereignty race. It is not only about who owns the seabed. It is about who can invest, who can insure, who can build, and who is allowed to operate.

The Economic Core: Critical Minerals, Rare Earths, And Processing Power

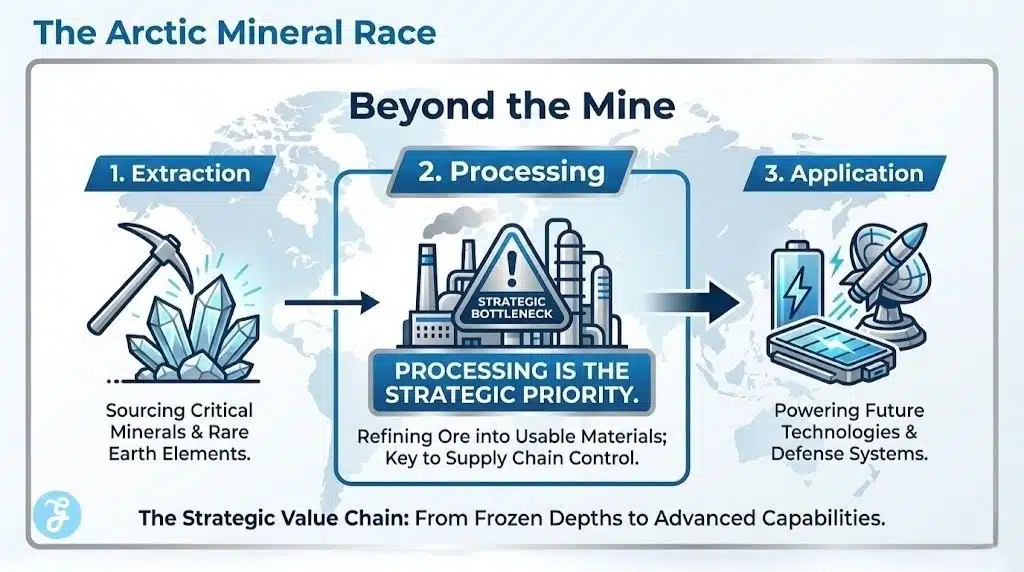

Oil and gas still matter in Arctic planning, but the economic center of gravity is shifting toward critical minerals and processing capacity. Rare earth elements, nickel, cobalt, and related materials are central to modern defense systems, electrification, and high-performance electronics. Within rare earths, certain heavy elements are especially valuable because they are harder to substitute in advanced applications.

This is why Greenland’s mineral potential draws intense attention. Large deposits are politically attractive because they promise strategic supply chain leverage. Yet the strategic bottleneck is not only mining. It is processing. If a country can extract ore but cannot process it into usable materials, it remains dependent on external systems.

That reality is reshaping Arctic resource debates. Governments and firms now focus on end-to-end capability. They look for secure offtake agreements, reliable logistics, and processing pathways that meet environmental standards and security screening.

This also changes how partnerships form. A mining company may need not only investors, but also allies who can provide processing, shipping insurance, and long-term purchase commitments. As a result, the Arctic resource race becomes a network contest. The strongest position goes to those who can build a full chain from deposit to finished component.

The trade-offs are real. Mining in the Arctic creates environmental concerns, high operating costs, and social tensions. Projects can also polarize local politics, especially when communities debate development versus preservation. The path forward requires stronger governance capacity, transparent benefit-sharing, and credible environmental enforcement.

In this context, Arctic sovereignty is not only about territory. It is about who sets the rules that govern extraction, who enforces them, and who gets the economic value.

The Shipping Reality: Promise, Limits, And Political Meaning

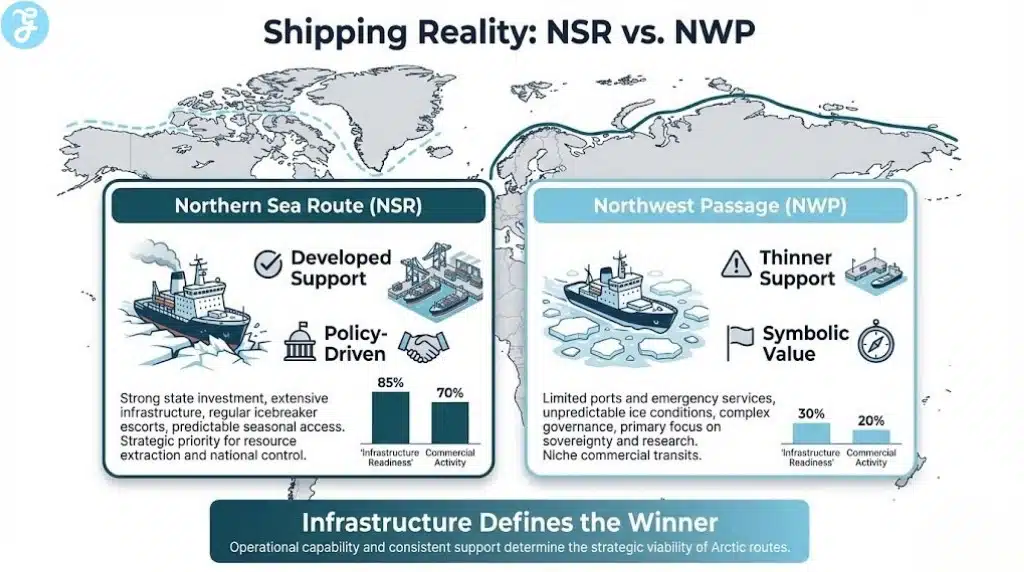

Arctic shipping is often described as a revolution, but the reality is more uneven. The Northern Sea Route can shorten distances between paerts of Asia and Europe. The Northwest Passage can offer a route through the Canadian archipelago. These options attract attention because they appear to reduce time and fuel.

However, the Arctic is not simply a shorter map line. It is a risk environment. Ice variability, fog, limited ports, and limited emergency capacity create uncertainty. For global supply chains, predictability is often more valuable than speed. That is why many mainstream container operators remain cautious, even as specialized and state-supported shipping grows.

Shipping in the Arctic also carries political meaning. Every transit touches sovereignty arguments. For Russia, the Northern Sea Route supports a national narrative of control, development, and revenue from escort and regulation. For Canada, the Northwest Passage is tied to claims of internal waters and to the capacity to enforce law and safety across a vast region.

There is also a cost reality. Ice-class ships are more expensive. Crew training is more demanding. Insurance can be higher. Seasonal windows can shift year to year. Even if overall ice declines, volatility can still disrupt planning.

The most likely near-term outcome is measured growth rather than a sudden takeover of global trade. State-supported cargo, energy exports, and specialized transits will grow. Cruise and research activity may increase as well. Full mainstream adoption by global container trade will remain limited until infrastructure, safety, and predictability improve.

A practical comparison helps clarify the routes.

| Metric | Northern Sea Route | Northwest Passage | International High Seas In The Central Arctic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Political Issue | Regulation and control along Russia’s coast | Legal status and enforcement capacity | Governance and future rules as access increases |

| Infrastructure | More developed support network | Thinner support network | Minimal infrastructure |

| Commercial Pattern | Growing, uneven, and policy-driven | Niche growth and symbolic value | Mostly science and monitoring |

The central point is that shipping is not just commerce. It is governance. Routes become arguments about law, capability, and authority.

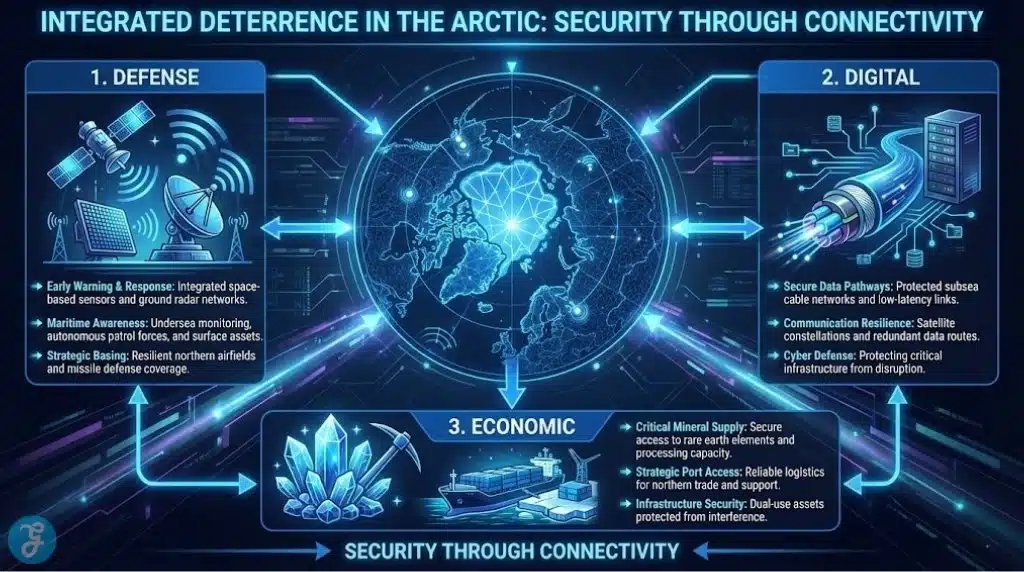

Subsea Cables, Data Routes, And The Digital Arctic

One of the least visible parts of the Arctic contest is the digital layer. Modern power relies on connectivity, data, and undersea infrastructure. The Arctic is increasingly discussed in terms of subsea cables, sensor networks, satellite coverage, and communications resilience.

These assets matter for three reasons. First, they support civilian life, emergency response, and economic activity in northern regions. Second, they support scientific monitoring and climate research. Third, they support military awareness and deterrence by improving detection and communication in a hard-to-monitor environment.

Digital infrastructure also creates vulnerabilities. Cables can be cut or tampered with. Sensors can be interfered with. Satellites can be jammed or spoofed. In a contested Arctic, protecting connectivity becomes a strategic mission.

This changes how governments define “resource control.” The resource is not only minerals and fuel. It is also bandwidth, data pathways, and the ability to see and act across the High North.

That digital focus also pushes cooperation in selective areas. Even rivals may share some safety and environmental concerns because accidents can be catastrophic in the Arctic. Still, cooperation is harder when trust is low and when infrastructure has dual-use value.

Integrated Deterrence In A Region Built For Endurance

The Arctic is becoming a laboratory for integrated deterrence because every domain overlaps. Air defense depends on space sensors and northern basing. Maritime awareness depends on satellites, undersea monitoring, and coordination with allied patrol forces. Economic resilience depends on trusted mineral supply chains, secure ports, and protected data links.

In this model, alliances matter as much as geography. States need partners to share costs and to coordinate response. They also need shared standards for investment screening, infrastructure security, and emergency operations.

This is where the Arctic can strain alliances as well as strengthen them. Partners may disagree on how far security policy should shape commercial decisions. They may also disagree on sovereignty sensitivities, especially around Greenland and the Northwest Passage. Even within aligned blocs, domestic politics can complicate agreements.

Still, the direction is clear. In early 2026, the Arctic is treated as a central theater, not a distant edge. That shift pushes defense budgets, infrastructure planning, and industrial policy into closer alignment.

Around this point, the core theme remains explicit: Arctic sovereignty resource control is the organizing concept that connects deterrence, minerals, shipping, and legal positioning.

What To Watch Through The Rest Of 2026

Several developments will reveal whether the region moves toward managed competition or sharper division.

First, watch basing and access arrangements, especially those tied to surveillance and missile defense. Expansions of access can strengthen deterrence but also raise sovereignty concerns and political backlash if they are framed poorly.

Second, watch whether critical mineral projects move from narrative to execution. The decisive milestones will be permitting, local consent, infrastructure buildout, and processing pathways. If projects cannot secure processing capacity, their strategic value will remain limited.

Third, watch how shipping patterns evolve. Growth in pilot transits can signal momentum, but a single high-profile accident or a sudden rise in insurance costs can chill activity quickly. In the Arctic, perception of risk can move faster than reality.

Fourth, watch governance. If Arctic cooperation becomes formally segmented into separate blocs, the region could face long-term legal and political bifurcation. That would change how states coordinate search and rescue, environmental response, and standards for infrastructure and transit.

Finally, watch infrastructure security incidents. Cable disruptions, cyber events, and suspicious maritime activity may become the most important indicators of whether competition is staying bounded or escalating.

The Race Is About Staying Power

The Arctic’s changing environment is not creating a simple rush. It is creating a contested arena where sovereignty, infrastructure, and industrial resilience collide. Oil and gas still influence planning, but the sharper contest is increasingly about critical minerals, data routes, and the ability to protect assets in extreme conditions.

This is why Arctic sovereignty resource control is no longer a theoretical map debate. It is a practical contest over endurance, governance, and supply chains. The actors that shape the Arctic’s future will be those that can build logistics that work through winter, maintain legitimacy with local communities, and keep partners aligned under pressure.

In 2026, the high-stakes race is not about who gets there first. It is about who can stay, who can defend what they build, and who can turn long-term access into lasting strategic advantage.