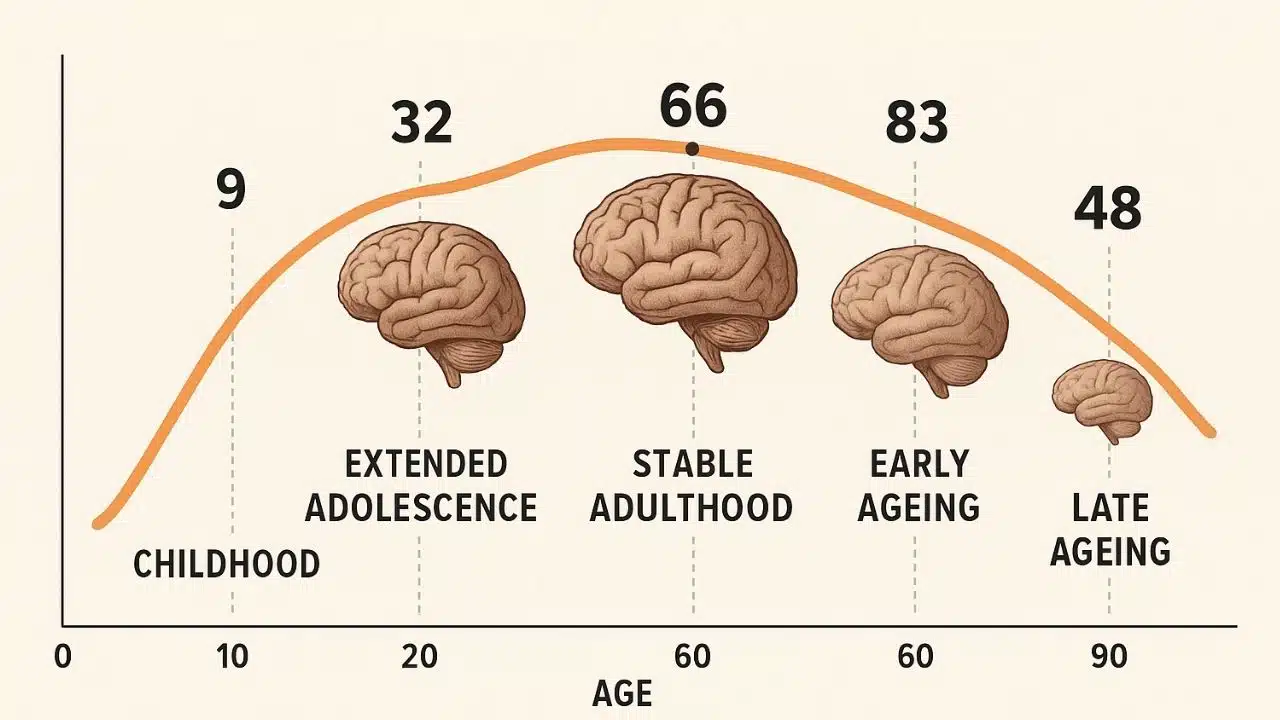

Neuroscientists at the University of Cambridge have mapped five major “eras” of human brain development — each separated by major turning points at around ages 9, 32, 66, and 83. Their study, based on MRI scans of more than 3,800 people aged between infancy and 90, shows that the brain does not mature or age in a smooth, linear way. Instead, it goes through dramatic reorganizations at specific stages of life. These shifts mark when the brain becomes more efficient, more vulnerable, or enters periods of stability or decline. Researchers say this new model helps explain why certain mental health disorders tend to emerge at particular ages, and why neurological risks rise sharply as people grow older.

The authors emphasize that this is the first study to clearly identify sweeping, lifespan-wide transitions in how the brain is wired. They describe these phases as biological epochs that define what the brain is best equipped to do at different times. Lead researcher Dr. Alexa Mousley explains that these eras give critical context for understanding both resilience and vulnerability: during some phases, the brain is strengthening and optimizing itself; in others, it becomes more susceptible to disruption.

The first era covers early childhood, which ends at around age 9. During this time, the brain goes through rapid construction and refinement. Neural connections form in huge numbers, and the brain grows quickly while also trimming away unused or inefficient pathways. This period is dominated by structural expansion, foundational learning, and establishing the basic architecture of major networks. The transition at age 9 marks the end of this intensely plastic phase and the beginning of a more complex reorganization that extends far into adulthood.

One of the most surprising conclusions of the study is the length of adolescence. While adolescence is commonly defined as ending in the late teens or early twenties, the researchers found that the brain continues reorganizing and increasing its efficiency until around age 32. According to the data, this point at 32 represents the single strongest turning point in the entire lifespan. The brain’s wiring undergoes its largest directional shift here, signifying the end of structural fine-tuning and the true beginning of stable adulthood. Dr. Mousley notes that while puberty marks the start of adolescence, science has never pinned down its biological end — and these findings provide the clearest evidence yet that it stretches deep into what society typically considers full adulthood.

The era between ages 32 and 66 is identified as the longest and most stable phase of life. During this period, major measures of intelligence and personality traits plateau. Brain networks operate at peak efficiency, and the architecture of connectivity remains remarkably consistent. This stability suggests that the mature adult brain is less about restructuring and more about maintaining equilibrium. However, stability does not imply stagnation; rather, it indicates that the brain’s essential systems of communication are functioning optimally without undergoing the major rewiring seen in earlier eras. This period is thought to support the most sustained cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and consistency in personal identity.

At age 66, the brain enters its first phase of aging. This stage is characterized by a noticeable decline in white-matter quality and reduced efficiency in connectivity. These changes happen in parallel with increased exposure to health risks such as hypertension, vascular problems, and metabolic issues — all of which can affect the brain. The research suggests that this period marks the beginning of vulnerability to age-related neurological conditions. Brain networks continue to function, but their integration becomes less robust. This decline is not typically severe at 66, but it signals the onset of the gradual weakening that becomes more pronounced in later years.

The final era, beginning around age 83, reflects deep aging in the brain. Connectivity weakens further, and previously well-coordinated regions become more isolated. Network communication becomes less efficient, and the brain’s ability to compensate for small disruptions diminishes noticeably. The researchers caution that this phase is the least understood due to the difficulty of collecting large MRI datasets from healthy individuals in their eighties and nineties. Still, the patterns observed show consistent and accelerating decline in structural integration. This weakening contributes to increased susceptibility to cognitive impairment, memory loss, and neurodegenerative diseases. Despite the decline, the study emphasizes that change is not uniform: some parts of the brain are more resilient than others, and lifestyle factors continue to play a significant role.

Senior author Professor Duncan Astle highlights that many people feel their lives are shaped by distinct periods — childhood, adolescence, adulthood, midlife, and older age. This research shows the brain follows its own clear shifts that align closely with these lived experiences. Instead of viewing aging as a slow, steady decline, the brain appears to move through specific reorganizing phases, each representing a different functional state. The turning points at 9, 32, 66, and 83 act like biological signposts for when the brain reconfigures itself.

The findings have major implications for mental health, education, public health planning, and even treatment timing. Understanding these eras can help researchers determine when the brain is most likely to undergo destabilizing changes — such as during late adolescence, when many psychiatric disorders first appear. It also provides insight into when early signs of neurological aging begin, giving medical experts a clearer target for interventions that support cognitive health.