Ethical Challenges in Blockchain are no longer a niche concern reserved for tech philosophers. As blockchain technology moves into finance, identity, supply chains, and even AI, the ethical questions around how it is built and used have become central to whether people can trust it at all. If you want to understand not just how blockchain works but whether it is good for society, you have to look closely at the real-world consequences, not just the code.

In this guide, we’ll unpack the main ethical issues in blockchain, show how they connect to privacy, governance, sustainability, and inclusion, and give you a practical way to think about them for products, policies, or investment decisions.

What Makes Blockchain Ethically Different?

Before diving into specific ethical issues, it helps to understand what makes blockchain special — and why that creates unique risks.

Key Features That Create Ethical Tension

| Blockchain Feature | What It Means in Practice | Ethical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Decentralization | No single central owner; many nodes share control | Hard to know who is responsible when things go wrong |

| Immutability | Data, once recorded, is very hard or impossible to change | Mistakes and harmful data can be permanent |

| Transparency | Many blockchains are public and auditable by anyone | Privacy and data protection become difficult |

| Automation via Smart Contracts | Code automatically executes agreements | Bugs can cause huge losses with no easy rollback |

| Global Reach | Operates across borders and legal systems | Jurisdiction and regulation become unclear |

These features are often presented as the reasons blockchain is powerful. But they are also why Ethical Challenges in Blockchain keep appearing in real-world cases, especially in decentralized finance (DeFi), non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and identity systems.

The Central Dilemma: Transparency vs Privacy

One of the biggest ethical issues in blockchain is the constant trade-off between transparency and privacy.

How Transparency Becomes a Privacy Problem

Public blockchains are designed so anyone can:

-

View transaction histories

-

Trace funds between addresses

-

Analyze activity patterns over time

Even if addresses are pseudonymous, researchers and companies can deanonymize users by connecting blockchain data with off-chain information such as exchange accounts, IP addresses, or payment records.

This creates several ethical and legal questions:

-

Data protection in blockchain: What happens when personal data gets written to an immutable ledger?

-

Right to be forgotten: If a jurisdiction guarantees people the right to erase data, how does that work with an unchangeable chain?

-

Surveillance risk: Governments, corporations, or malicious actors might track individuals’ financial or social behavior indefinitely.

On-Chain vs Off-Chain: A Better Design Choice

To cope with these blockchain privacy concerns, many responsible projects:

-

Store personal data off-chain in secured databases or distributed storage.

-

Store only hashed references or proofs on-chain.

-

Use zero-knowledge proofs and selective disclosure so users can prove something (for example, “over 18”) without revealing their full identity.

This kind of privacy-by-design mindset is crucial if you want to talk about the ethical use of blockchain technology in any serious way.

Security Risks, Hacks, and Consumer Protection

Security is often framed as a technical issue, but it is also a moral one. When a system is advertised as trustless and safe, and ordinary people lose money due to design flaws or scams, that’s a major ethical concern.

Common Security and Ethical Issues

-

Smart contract vulnerabilities: Bugs in code can lock or drain funds. Once deployed, smart contracts are often difficult to patch without a hard fork or special admin powers.

-

DeFi protocol exploits: Cross-chain bridges, lending platforms, and liquidity pools are frequent targets. When they are hacked, retail users — not just sophisticated investors — can lose everything.

-

Rug pulls and exit scams: Anonymous teams raise money, pump a token, then disappear with the liquidity. This blends technical risk with outright fraud.

Why This Is an Ethical Problem

These are not just “user beware” situations. They raise deeper questions about:

-

The duty of care that developers and protocol founders owe to users

-

Whether “code is law” is being used to escape responsibility

-

How far should consumer protection extend in a permissionless ecosystem

Ethical blockchain projects now treat security, audits, and transparency as non-negotiable, not optional. They often publish code, commission third-party audits, run bug bounty programs, and explain risks clearly instead of hiding behind jargon.

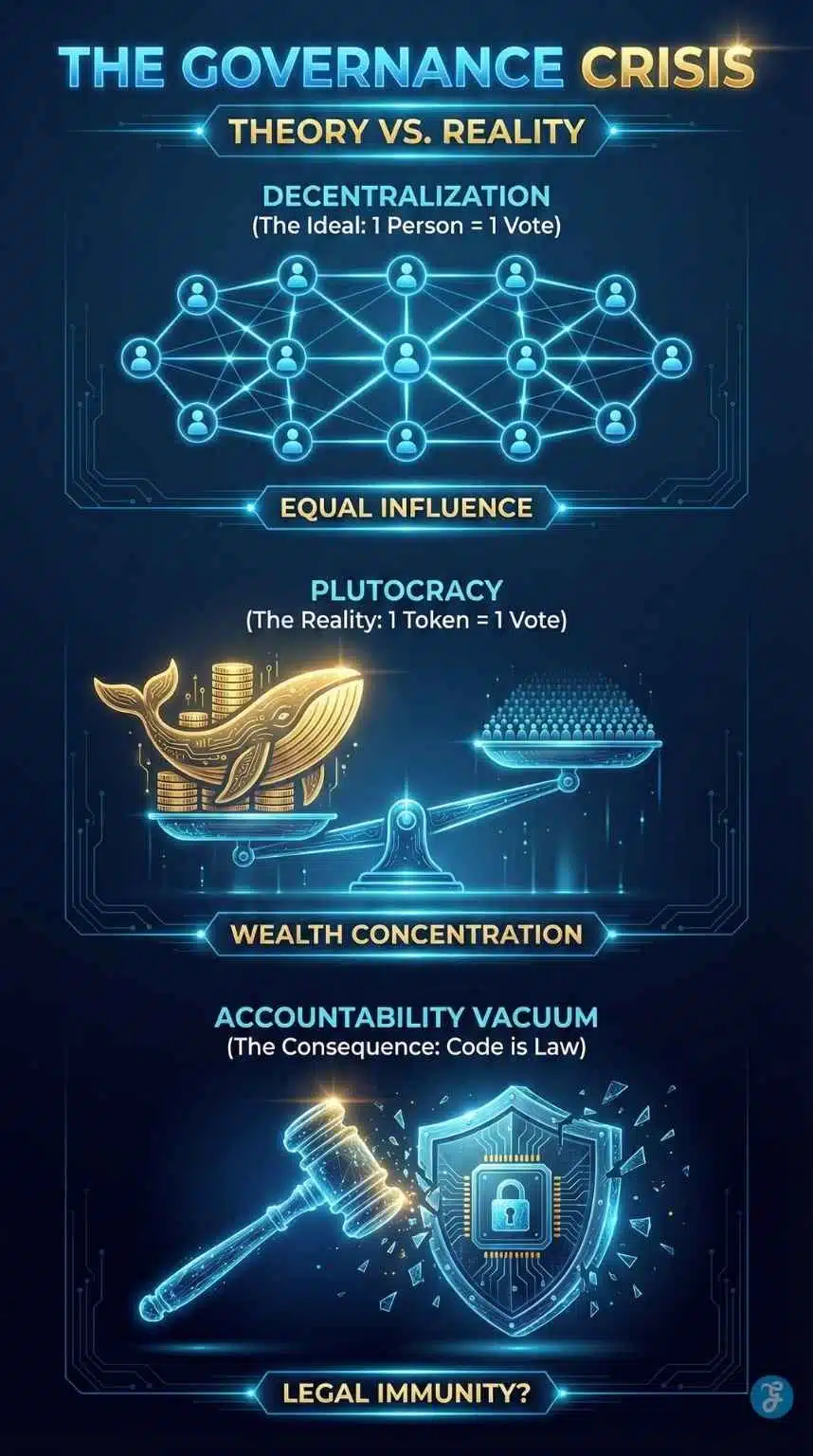

Governance and Power: Is Decentralization Just a Myth?

From the outside, blockchain is sold as decentralized, leaderless, and democratic. But when you look deeper, the reality can be very different.

How Power Actually Works in Blockchains

-

Whale dominance: A few large holders (whales) can control governance votes.

-

VC-backed protocols: Early investors may hold concentrated voting power.

-

Centralized infrastructure: Key services (like oracles, front-ends, or hosting) are often controlled by a few companies.

This creates blockchain governance challenges that are both technical and ethical:

-

If a protocol can be upgraded by a small group, is it really decentralized?

-

If a DAO vote is dominated by a few addresses, is that fair governance?

-

If a decision harms users, who should be held accountable: the protocol, the DAO, or individual developers?

Governance Ethics: Key Questions to Ask

Ethical blockchain governance should be evaluated by questions like:

| Governance Area | Ethical Question |

|---|---|

| Voting Power | Is voting concentrated among a few wealthy token holders? |

| Transparency | Are governance processes and decisions clearly documented? |

| Accountability | Who takes responsibility when decisions cause harm? |

| Inclusivity | Can everyday users meaningfully participate in decisions? |

If a project fails these tests, its claims of decentralization need to be challenged — especially in media, research, and regulatory debates.

Environmental Impact: Beyond Just Energy Consumption

For years, the environmental debate focused entirely on the massive energy consumption of proof-of-work (PoW) blockchains like Bitcoin. While this remains a valid concern, the conversation regarding the environmental impact of cryptocurrency has evolved into a more nuanced discussion about hardware and efficiency.

The E-Waste Problem

The carbon footprint of crypto isn’t just about electricity; it’s about the hardware lifecycle. Mining requires specialized, high-performance hardware (ASICs) that becomes obsolete rapidly—often within 1.5 to 2 years. Unlike a standard laptop, which can be resold or repurposed, an obsolete ASIC miner is essentially useless metal and silicon.

This generates thousands of tons of electronic waste (e-waste) annually. The ethical challenge here is material: Are we extracting rare earth minerals and filling landfills just to secure a digital ledger?

The Jevons Paradox in Blockchain

With the industry moving toward “greener” consensus mechanisms like Proof of Stake (PoS), a new ethical phenomenon known as the “Rebound Effect” (or Jevons Paradox) emerges. As blockchain transactions become cheaper and less energy-intensive, the total volume of transactions creates a massive spike in usage. If the network scales to billions of users, the aggregate energy draw of the supporting infrastructure (servers, nodes, user devices) could still be massive, even if individual transactions are efficient.

| Metric | Proof of Work (PoW) | Proof of Stake (PoS) | Ethical Concern |

| Energy Source | Computational Power (Mining) | Capital Commitment (Staking) | PoW burns energy; PoS favors the wealthy. |

| Hardware | Single-use ASICs | General Servers/Laptops | PoW creates massive e-waste; PoS is cleaner but centralizes control. |

| Security Model | Physical Energy Cost | Economic Penalty | PoW is harder to attack but hurts the planet; PoS is “greener” but theoretically closer to traditional banking. |

Social Impact: Inclusion, Inequality, and Access

Blockchain is often marketed as a tool for financial inclusion, promising to bring banking and digital assets to the unbanked. But reality is more complicated.

Inclusion vs Inequality

On the one hand, blockchain can:

-

Provide access to digital payments without a bank account

-

Enable cross-border transfers that bypass predatory intermediaries

-

Offer new forms of ownership and participation

On the other hand, the ecosystem can reinforce inequality:

-

Early insiders and technically skilled users often capture most of the gains

-

Complex products expose inexperienced users to extreme risk

-

High transaction fees can price out low-income users on popular networks

The question is not just whether blockchain can help financial inclusion, but whether it is designed in a way that does not push risk onto those who can least afford it.

Access Barriers and Ethical Design

True ethical use demands that projects consider:

-

Digital literacy: Can people understand what they’re doing?

-

Language access: Is information provided in multiple languages, in clear terms?

-

Hardware and connectivity: Are users expected to have constant, fast internet and modern smartphones?

If the design only works for educated, well-connected users in rich regions, claims about global inclusion become more like marketing than reality.

The AI and Blockchain Connection: New Ethical Frontiers

Now there is a growing intersection between AI and blockchain, and it comes with its own ethical questions.

Potential Benefits

-

Using blockchain as a transparent log of AI model changes and data sources

-

Tracking how AI outputs are generated for better accountability

-

Creating auditable records of who accessed what and when

In theory, this can support stronger AI accountability and prevent some hidden manipulation.

New Risks

However, the same combination can be dangerous:

-

Surveillance systems that use AI and store sensitive data on-chain can become almost impossible to undo.

-

Biased or harmful models could be cemented via decentralized distribution, making it harder to correct or control.

-

The combined energy usage of intensive AI and blockchain infrastructures raises new sustainability questions.

The key question: Are we using blockchain to restrain AI abuses, or to amplify them and make them permanent?

A Practical Framework for Thinking About Ethical Challenges in Blockchain

It’s easy to get lost in details. To make things manageable, you can use a simple framework built on four core tensions that appear in almost every serious blockchain debate.

1. Transparency vs Privacy

-

What absolutely must be transparent for trust and accountability?

-

What absolutely must remain private for safety, dignity, or legal compliance?

-

Are you using privacy-enhancing tools such as encryption and zero-knowledge proofs?

2. Decentralization vs Accountability

-

Who can make changes, shut things down, or override bad outcomes?

-

Is decentralization real or just a marketing story?

-

When something goes wrong, who should users turn to?

3. Innovation vs Precaution

-

Are users exposed to extreme or poorly understood risks?

-

Are there audits, risk disclosures, and gradual rollouts?

-

Is experimentation happening with play money or people’s life savings?

4. Security vs Sustainability

-

Does the security model require large amounts of energy?

-

Are there alternative designs that would be safer or more sustainable?

-

Is the system resilient to attacks without costing the planet?

You can treat these tensions as a mental checklist whenever you analyze or build a blockchain system.

Quick Ethical Review Checklist for Any Blockchain Project

To make your analysis more structured, use a checklist like this:

| Dimension | Key Questions to Ask |

|---|---|

| Stakeholders | Who benefits, who takes the risk, and who never got a choice? |

| Rights & Protections | Are user rights (privacy, redress, informed consent) clearly protected? |

| Power Dynamics | Who actually controls the protocol, governance, and infrastructure? |

| Risk & Harm | What are the worst-case scenarios, and who would be most affected? |

| Regulation & Law | Does the design align with financial regulation and data protection rules? |

| Environment | What is the energy footprint, and is anything being done to reduce or offset it? |

If a project cannot offer honest, concrete answers, it signals serious ethical gaps.

Best Practices for More Ethical Blockchain Design

When teams and policymakers want to address Ethical Challenges in Blockchain proactively, several best practices keep coming up.

1. Privacy-by-Design and Data Minimization

-

Avoid storing personal data on-chain whenever possible

-

Use off-chain storage and on-chain proofs

-

Give users control over what they reveal and to whom

2. Strong Security and Honest Risk Disclosure

-

Commission independent audits and publish the results

-

Run bug bounty programs to incentivize responsible disclosure

-

Present risks in simple language, not just technical whitepapers

3. Fair and Transparent Governance

-

Clearly document how decisions are made and how voting works

-

Limit governance capture by whales through thoughtful tokenomics or alternative voting models

-

Provide channels for feedback, dispute resolution, and due process

4. Sustainability as a Core Design Goal

-

Prefer energy-efficient consensus algorithms where possible

-

Consider the environmental cost of every design choice

-

Be transparent about energy use and mitigation measures

5. Inclusion and Accessibility

-

Design for users with different levels of literacy and internet access

-

Offer multilingual resources, FAQs, and tutorials

-

Support community education instead of relying solely on hype and speculation

These steps do not magically make a system “perfectly ethical,” but they show that a team takes blockchain ethics seriously and is willing to be judged on more than token price.

Future Outlook: Toward Responsible Blockchain Ecosystems

The conversation around ethical issues in blockchain is moving from “Is this technology good or bad?” to “Under what conditions is this technology acceptable or beneficial?”

In the future, expect:

-

Stricter expectations from users and regulators around accountability and consumer protection

-

More pressure to measure and reduce environmental impact

-

Growing demand for explainable and transparent governance in decentralized systems

-

Tighter integration of blockchain with AI, making discussions about ethical AI and ethical blockchain almost inseparable

Projects that respond early, with real transparency and ethical design choices, are more likely to earn long-term trust than those that hide behind slogans and technical jargon.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the main ethical issues in blockchain?

The primary ethical issues include data privacy conflicts (immutability vs. GDPR), high environmental costs (energy and e-waste), wealth inequality, governance centralization in DAOs, and the facilitation of illegal activities.

How does blockchain affect the environment beyond energy use?

Beyond electricity, blockchain networks contribute significantly to electronic waste (e-waste) due to the rapid obsolescence of specialized mining hardware (ASICs), which often cannot be repurposed.

Can blockchain data ever be deleted?

Generally, no. Blockchain is designed to be immutable, meaning once data is written to the ledger, it cannot be altered or deleted. This creates conflicts with privacy laws that grant users the “Right to be Forgotten.”

What is “Predatory Inclusion” in crypto?

Predatory inclusion refers to marketing high-risk, volatile financial products to marginalized or low-income groups under the guise of “financial inclusion,” often exposing them to losses they cannot afford.

Final Thoughts

Ethical Challenges in Blockchain are not side issues to be handled after launch; they are central to whether the technology deserves a place in critical systems like finance, identity, and governance.

By thinking carefully about transparency vs privacy, decentralization vs accountability, innovation vs precaution, and security vs sustainability, you can evaluate any blockchain system more clearly — and push the ecosystem toward more responsible, human-centered innovation.