Firoz Sheikh knew the language of bricks. Morning after morning, he mixed cement by instinct, lifted stones by memory, measured walls by eye. A mason from Murshidabad, his days followed a steady rhythm. Work. Home. Rest. Repeat. His body understood weight, balance, endurance. Nothing abstract. Nothing fragile.

That morning was no different. The sun was already sharp. The dust familiar. His hands moved the way they always had. And then they did not.

There was no warning. No pain that announced itself. One second he was standing. The next, the world slipped away. Darkness arrived without permission. What came next would lead him to Dr Amitabha Chanda brain surgery, where precision would decide how much of his life he could return to.

This story does not begin with a miracle. It begins with vulnerability.

When a Scan Turns Life Fragile

The hospital room was quiet in a different way.

Not the quiet of rest, but the waiting kind. The kind that stretches time. A CT scan was ordered. Routine words. Technical. Reassuring on the surface. Firoz lay still as the machine circled his head, recording what the eye could not see.

When the report came, it arrived dressed in clinical language. Measured. Detached. A large mass in the frontal region of the brain.

A tumour. The word landed heavily, even as the sentence around it remained calm. The frontal brain. It controls thinking. Seeing. Being aware. It guides how we act and who we are.

For Firoz, this was not theory. It was personal. His vision mattered. His speech mattered. His balance. His hands. His ability to return to work. To earn. To remain himself.

Conventional brain surgery would mean a long incision. Bone removed. Weeks of recovery. Possible damage that no scan could fully predict. For a man whose life depended on physical strength and steady coordination, the cost could be permanent.

This was not just about removing a tumour. It was about what might be lost along the way.

A Surgeon Who Chooses Calm Over Force

Dr Amitabha Chanda walks into a room quietly. No noise there. Nothing rushed, nothing sharp in his voice. At C K Birla Hospitals in Kolkata, where he is Senior Consultant and Director of Neurosurgery, calm seems to follow him everywhere. Perhaps that is his method.

He listens first. To the patient. To the family. To the silence between questions.

Decades in the operating theatre have taught him that the brain does not respond well to haste. More than thirty-five years of surgical experience have refined something rarer than speed. Restraint.

His training spans institutions in India and abroad, shaped by gold medal academic distinctions and international exposure. But none of that is recited when he meets a patient. What matters more is judgment. Knowing when to act. Knowing when not to.

Colleagues describe him as precise. Patients describe him as reassuring. Both are true. Dr Chanda operates with the belief that every movement leaves a memory inside the brain, and that surgery must solve a problem without creating a new one.

When he reviewed Firoz Sheikh’s scans, he did not see a case. He saw a life that needed to return intact. For Firoz Sheikh, the path forward would rely on Dr Amitabha Chanda brain surgery, where every move is measured, and the goal is to heal without harm.

A Tumour Where Millimetres Decide Everything

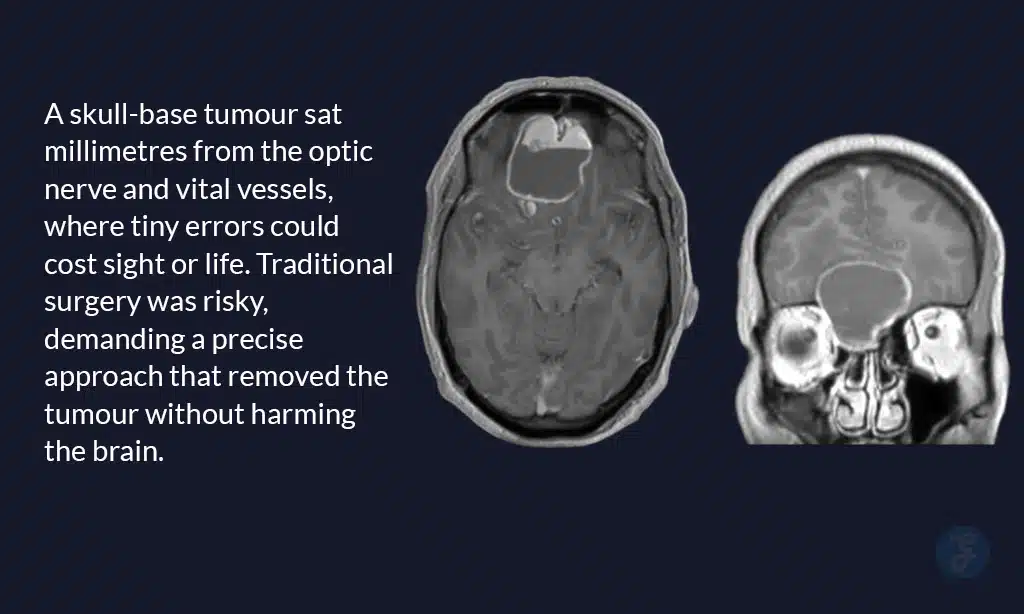

The MRI told a more complicated story.

The tumour was not simply large. It was positioned deep at the base of the skull, tucked just behind the forehead. A narrow, unforgiving space. On one side lay the optic nerve, responsible for sight. On the other, vital blood vessels that feed the brain. There was no margin for error.

“In this location, even a few millimetres can change a life,” Dr Chanda said quietly. “Vision can be lost. Speech can be affected. Blood supply to the brain can be compromised.”

Traditionally, tumours like this are approached by opening the skull widely. A long incision across the forehead. Bone lifted and removed. The brain gently but inevitably retracted to reach the growth beneath. It is effective surgery, but it is also forceful.

Recovery is slow. Swelling takes time to settle. The risk of complications lingers. For many patients, especially those who depend on physical strength and clarity of movement, the aftermath can be as life altering as the disease itself.

This was not a routine case. It was a test of precision, patience, and judgment. And it demanded a path that would treat the tumour without punishing the brain.

When Surgery Becomes an Ethical Decision: Dr Amitabha Chanda Speaks

For Dr Amitabha Chanda, the question was never only how to remove the tumour.

It was how to do it without taking something else away.

Years in neurosurgery had taught him a simple truth. The brain is not forgiving. It remembers. Every pull, every unnecessary exposure, every moment of force leaves an imprint. Even when the tumour is gone, the trauma can stay.

“Surgery should solve a problem,” he often says, “not create a new one.”

This belief sits at the heart of his practice. That less can be more. That access does not have to mean aggression. That healing should not come wrapped in fear.

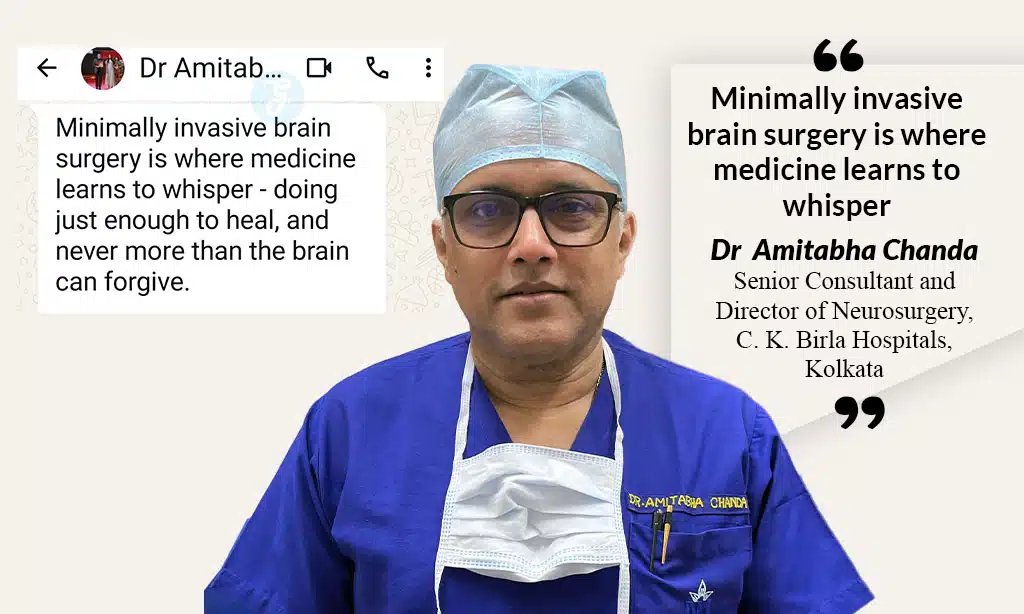

Minimally invasive surgery, in his hands, is not a shortcut or a trend. It is an ethical position. A commitment to intervene only as much as needed. To respect the brain as an organ that governs identity, dignity, and independence.

“Minimally invasive brain surgery is where medicine learns to whisper,” Dr Chanda says. “Doing just enough to heal, and never more than the brain can forgive.”

For Firoz Sheikh, this philosophy would shape everything that followed.

Choosing the space between the eyebrows

The decision did not arrive dramatically.

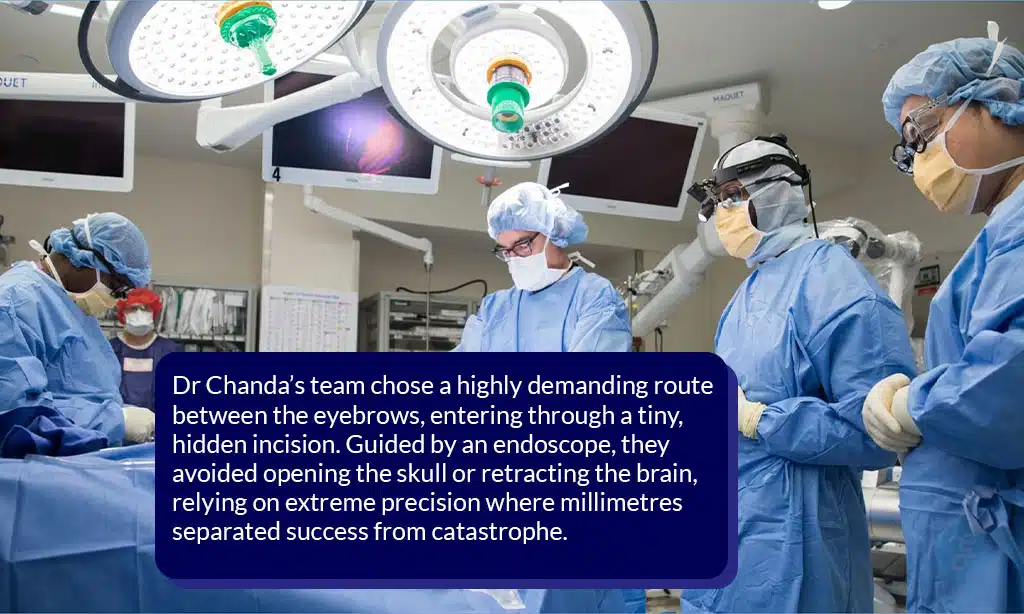

There was no announcement. No flourish. Just a quiet agreement among people who understood what was at stake. Dr Chanda and his team chose an approach that demanded more from the surgeon so that it would demand less from the patient.

They would go in through the space between the eyebrows.

It is one of the most technically demanding routes in neurosurgery. A narrow corridor. Limited visibility. No room to adjust once inside. Not every surgeon is trained for it. Not every hospital is equipped to support it. Precision here is not optional. It is everything.

The incision would follow a natural facial crease along the bridge of the nose, hidden within the brow line. When healed, it would be almost invisible. No wide opening of the skull. No aggressive retraction of the brain. Just a carefully planned path guided by an endoscope.

Through that small opening, the surgeon must navigate past structures that cannot be disturbed. The optic nerve. Critical blood vessels. Millimetres decide success or catastrophe.

Choosing this path was not about innovation for its own sake. It was about courage. About trusting experience. About believing that the most respectful way into the brain is often the quietest one.

Inside the Operation Theatre During a High Risk Brain Surgery

Inside the operation theatre, there was no drama to watch.

The lights were steady. The room calm. Every movement deliberate. Through the small incision between the eyebrows, an endoscope became the team’s eyes, projecting a magnified world where precision was the only language that mattered.

Here, there was no space for haste. Millimetres decided outcomes. Dr Chanda advanced slowly, navigating a terrain where the optic nerve lay close and vital blood vessels pulsed quietly nearby. Nothing could be disturbed. Nothing could be rushed.

The tumour was not pulled out. It was reduced, carefully, bit by bit. Each fragment removed with patience. Each pause is intentional. The brain was not asked to move aside. It was respected.

This kind of surgery does not reward force. It rewards restraint. Control. The confidence to do less when less is enough.

Hours passed in this quiet concentration. When the final piece was removed, there was no moment of celebration. Just confirmation. The structures were intact. The brain undisturbed.

Mastery in neurosurgery often looks like this. Almost invisible. Almost silent. But exact in every way that matters.

After Surgery, Life Returns Quietly

The first confirmation came from the scans.

The images were clear. The tumour was gone. The surrounding brain was untouched. No swelling that raised concern. No hidden damage waiting to reveal itself later.

Then Firoz woke up.

His eyes opened easily. His vision was clear. He spoke without effort. There was no weakness in his limbs. No confusion. No sense of being lost inside his own body. Everything that mattered was still there.

By the next day, he was ready to go home.

Less than twenty-four hours after a brain tumour had been removed, Firoz walked out of the hospital. No long stay. No extended recovery. No uncertainty about what he would regain.

The incision was small. Tucked neatly along the natural line between his eyebrows. As the days passed, it faded into the brow, almost impossible to notice. A scar that refused to announce itself.

The results did not demand attention. They simply allowed life to continue.

A Surgeon’s Belief, Spoken Aloud

For Dr Amitabha Chanda, the outcome was never just about what a scan showed. It was about what the patient carried back into life.

He measures success by what remains untouched. Clear speech. Steady hands. Confidence in one’s own body. Surgery, in his view, should leave no shadow behind.

Aggression has its place, he believes. But not everywhere. Not always. Especially when experience and technology allow a gentler path. To him, dignity is not an added benefit of good surgery. It is the standard by which it is judged.

A patient should recover without fear settling into the body. Without the feeling that survival demanded too much in return.

In Firoz Sheikh’s case, success meant more than removing a tumour. It meant returning a man to his work, his strength, and his sense of self, without asking the brain to carry the memory of violence.

When Advanced Care Reaches Ordinary Lives

Stories like this are often assumed to belong to a certain world.

Private hospitals. Elite patients. People who live close to cities and far from uncertainty. Advanced neurosurgery, many believe, is reserved for those who already have access to everything else.

Firoz Sheikh disrupts that assumption.

A mason from Murshidabad, he had no influence. No privilege. Just a medical emergency. What followed was world-class care. Not because of who he was, but because of what could be done.

C K Birla Hospitals are changing what access to advanced care can look like. With investment in expertise, training, and technology, they are bringing high-end neurosurgery closer to everyday lives. Surgeons like Dr Amitabha Chanda take that responsibility seriously. Excellence here is not something kept behind closed doors. It is something shared.

This shift matters now more than ever. As healthcare advances, the real question is not how sophisticated it becomes, but who it reaches. In this case, it reached a man whose hands build homes for others, and returned him safely to his own life.

That is what progress looks like when it is done right.

Where Experience Meets New Surgical Tools

Neurosurgery is changing, and the change is visible.

Endoscopic approaches are allowing surgeons to work through smaller openings. Incisions are shorter. Hospital stays are reduced. Recovery is faster. For patients, the difference can be life altering.

But technology, on its own, is not enough.

An endoscope does not make decisions. It does not sense when tissue must be left alone. It does not know when stopping is wiser than pushing forward. Those choices come only from years spent inside operating theatres, learning what the brain will tolerate and what it will not.

Dr Amitabha Chanda stands at that intersection. Trained in an era of open surgeries and long recoveries, he carries the discipline of traditional neurosurgery. At the same time, he has embraced newer methods that reduce harm when used with care. The balance between the two is not automatic. It is earned.

In his hands, innovation is guided by experience, not excitement. New tools are used not to impress, but to protect. The goal remains unchanged. Remove disease. Preserve life as it was lived before.

This is what the future of neurosurgery looks like when it is shaped by judgment, not just progress.

Back to Life, Without a Visible Trace

Firoz Sheikh is back where he belongs.

At home. Among familiar walls. His body is moving the way it always has. The work has resumed. The days follow their old rhythm again. Nothing about him announces what he has been through.

There is no heavy scar to explain. No visible reminder of a life interrupted. Only a faint line, hidden between the eyebrows, resting in a natural crease. Easy to miss. Easier to forget.

That small space carried a great deal. It allowed doctors to reach deep into the brain and return without leaving damage behind. Science passed through quietly. And left no mark worth noticing.

For Firoz, gratitude is simple. He is alive. He can see. He can work. He can continue being himself.

The space between two eyebrows is not meant to be remembered. And that may be the greatest success of all.

When Medicine Meets Life

What this story shows is quietly simple. Advanced medical care is often thought of as distant. Something for cities, elites, or those who can afford it. Yet here was a man who worked with his hands, ordinary in every way, getting treatment that decades ago would have meant weeks of recovery, risk, and visible scars.

Innovation in surgery is not just about tools or technology. It is about judgment, patience, and respect for the person behind the disease. Dr Amitabha Chanda’s work illustrates how experience and skill can make complex procedures safer, faster, and less intrusive, without ever compromising care.

For ordinary patients across India and elsewhere, the lesson is reassuring. World-class medicine can reach beyond expectation. It does not have to be exclusive. And when it does, it transforms not only bodies, but the way people imagine what is possible for themselves and their families.