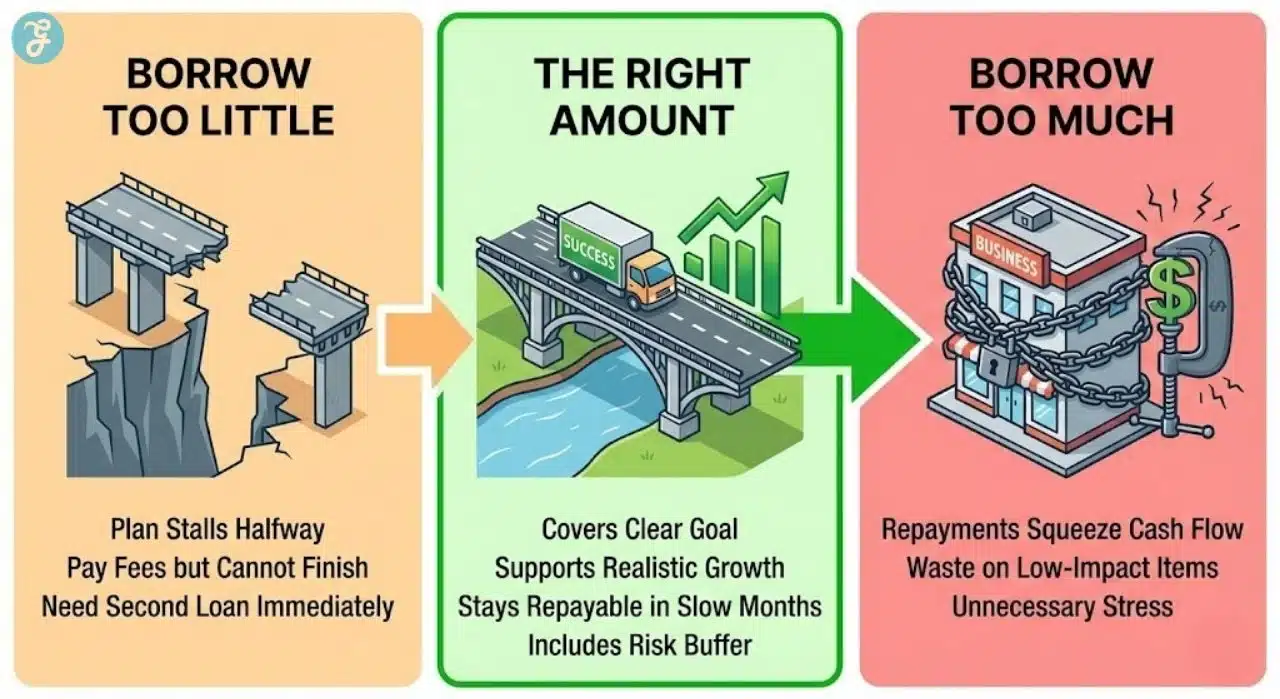

Getting financing is often easier than using it wisely. Borrow too little and your plan stalls halfway through. Borrow too much and repayments squeeze your cash flow, limit flexibility, and create stress you did not need. The right loan amount for your business is the smallest amount that covers a clear goal, supports realistic growth, and stays repayable even when sales dip.

This guide shows you how to calculate a loan amount based on numbers you can defend: cost breakdowns, timing, cash flow, and expected return. It also explains how to build a buffer without turning the loan into a future problem.

Right Loan Amount vs. Maximum Approval: Two Totally Different Numbers

A lender’s maximum offer is based on their risk model, collateral, and credit profile. Your “right amount” is based on your plan, timing, and cash flow tolerance. Those numbers often do not match.

A simple way to frame it:

-

Maximum approval = what you can borrow

-

The right loan amount = what you should borrow to hit a specific result without squeezing operations

If you treat approval as validation, you’ll tend to oversize the loan. If you treat the loan as a tool, you’ll size it to the smallest amount that completes the plan and stays comfortable during slow months.

Why Choosing the Loan Amount Matters More Than Getting Approved

Approval is only the starting line. The real risk starts after the funds arrive. Your loan amount sets the size of your monthly obligation and the level of pressure your business will carry until the debt is cleared.

A business can be profitable on paper and still run into trouble if repayment timing does not match revenue timing. Seasonality, slow-paying clients, and unexpected cost spikes can make a “reasonable” loan feel heavy. Choosing the right amount is about protecting operating stability, not chasing maximum borrowing capacity.

Overborrowing also creates waste. Extra money often gets spent on low-impact upgrades, unnecessary inventory, or scattered marketing. Under-borrowing creates a different type of waste: you pay fees and interest but still cannot finish what you funded. The right amount prevents both outcomes.

What Does “Right” Mean When You Borrow for Business

The right loan amount is not a universal number. It depends on what you are funding, how predictable your cash flow is, and how quickly the investment pays you back.

In practical terms, the right amount usually meets four conditions:

-

It funds a specific purpose with a clear budget

-

It includes realistic timing for costs and revenue impacts.

-

It fits your cash flow with room for slow months

-

It supports a return that is higher than its total borrowing cost

If any of those conditions fail, the loan amount is likely wrong, even if you can technically qualify for it.

The 3 Loan Categories That Change How Much You Should Borrow

Not all borrowing behaves the same, so the “right amount” changes depending on what the loan is doing.

Growth Investment Loans (expansion, equipment, marketing in proven channels)

These should be sized to pay back through measurable returns. The right amount usually depends on:

-

expected margin on new revenue (not just revenue)

-

ramp-up time (how long until returns show up)

-

operating costs required to sustain the growth

Working Capital Loans (cash flow gaps, inventory timing, seasonal dips)

These should be sized around timing problems, not profitability. The right amount usually depends on:

-

how long cash is tied up before you get paid

-

the size of your monthly fixed costs

-

worst-case collections delay

Rescue Borrowing (covering losses or “keeping the lights on”)

This is the highest risk category. If borrowing is required to cover ongoing operating losses, the “right amount” is often smaller than you want, and the better move may be cutting costs, renegotiating terms, or restructuring before adding debt pressure.

Knowing which category you’re in prevents you from using a growth-sized loan for a cash timing problem (or vice versa).

How Revenue Predictability Should Influence Borrowing Decisions

Predictability matters more than raw revenue size. A business earning $40,000 consistently each month may safely handle more debt than a business earning $80,000 sporadically.

When revenue is predictable:

-

Repayment planning becomes easier

-

Cash flow buffers can be smaller

-

Loan terms can be tighter without added stress

When revenue is unpredictable:

-

Loan amounts should be smaller

-

Repayment timelines should be longer

-

Buffers should be more conservative

Businesses with subscription models, retainers, or long-term contracts usually tolerate higher loan amounts better than businesses reliant on one-off sales or seasonal demand.

Use Your Cash Conversion Cycle to Avoid Borrowing the Wrong Amount

Many businesses don’t struggle because they’re unprofitable—they struggle because cash moves slowly.

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) in plain language

It’s how long money is tied up between paying for inputs (inventory, labor, materials) and receiving cash from customers.

A simplified way to think about it:

-

If you pay suppliers today but customers pay in 45 days, your loan must cover that gap.

-

The longer the gap, the more working capital you need—even if sales are strong.

Quick warning signs your CCC is stretching you

-

you’re growing sales but cash is always tight

-

you rely on delayed client payments to make payroll

-

inventory sits longer than expected

-

your busiest season creates the biggest cash pressure

If your borrowing is for working capital, CCC often determines the right amount more accurately than revenue totals.

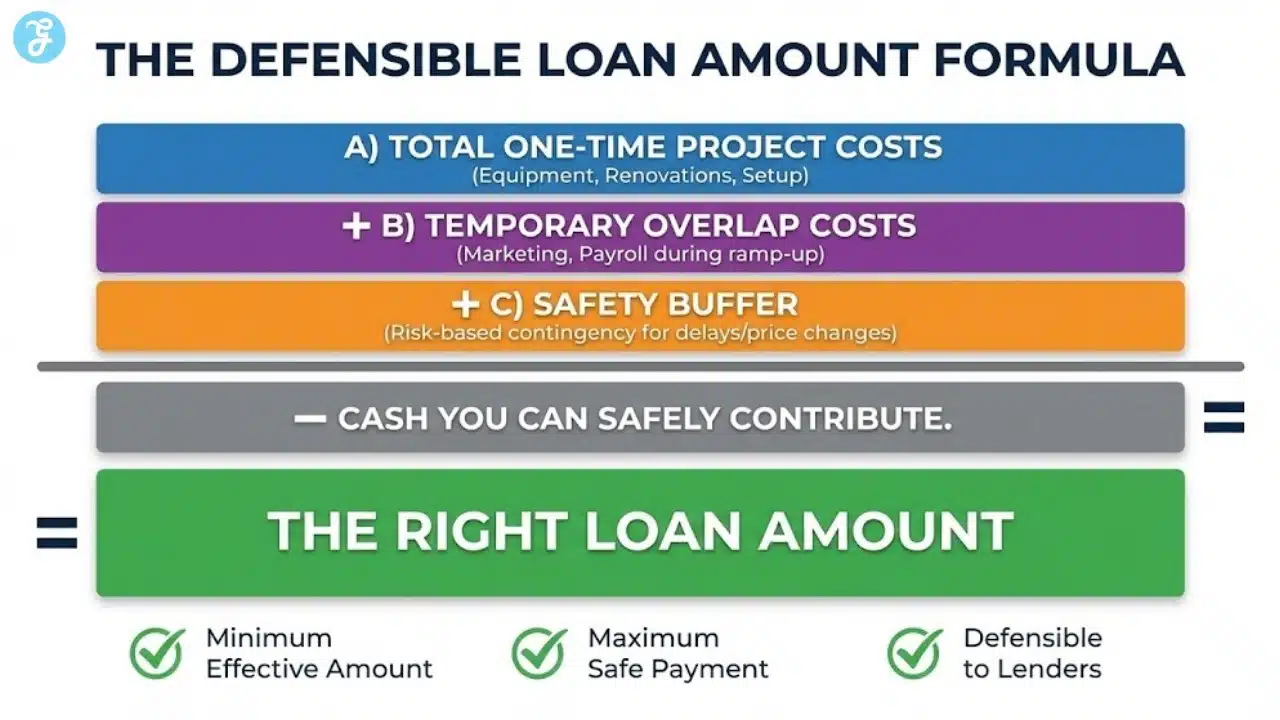

The One-Page Loan Amount Worksheet (So You Don’t Guess)

Before you start the steps, set up a simple structure you’ll fill in as you go:

A) Total Project Costs (one-time)

Add every item required to complete the plan.

B) Temporary Overlap Costs (short-term ongoing)

Extra payroll, marketing, software, training, or rent that exists during ramp-up.

C) Timing Gap (months)

How many months will you spend money before returns hit?

D) Safety Buffer (risk-based)

Contingency based on realistic delays, price changes, and slower revenue ramp.

At the end, your defensible loan amount should look like:

Loan Amount = A + B (for the overlap period) + Buffer – Any cash you can safely contribute

Here Are 8 Steps to Determine the Right Loan Amount for Your Business

Follow these steps in order. They help you move from guesswork to a defensible number you can explain to a lender, partner, or your future self.

1. Define the Exact Purpose of the Loan

Start by writing one sentence that explains what the loan will accomplish. If the purpose is vague, the amount will be vague too. Good loan purposes are measurable and tied to operations or growth.

Examples of clear purposes:

-

Purchase inventory to meet confirmed demand

-

Upgrade equipment to increase production capacity

-

Fund a marketing campaign tied to a proven channel

-

Cover working capital during a seasonal gap

-

Renovate a space to meet compliance or expand service

If you cannot explain the purpose clearly, pause before you borrow. Loans should fund a plan, not uncertainty.

2. List Every Cost Item the Loan Needs to Cover

Once the purpose is clear, build a cost list. Do not rely on memory. Make it a line-by-line budget.

Your list might include:

-

Inventory of raw materials

-

Equipment or software

-

Contractor or labor costs

-

Licensing, permits, or compliance fees

-

Shipping, installation, and training

-

Marketing spend and creative production

-

One-time setup costs and onboarding

This is where many business owners overborrow. They forget the supporting costs that come with the “main” expense. Those supporting costs can be the difference between success and a half-finished project.

Build a “Use of Funds” Table (This Prevents Cost Blind Spots)

Once you list costs, organize them into a table format so nothing hides in your notes. Include:

-

item name

-

vendor estimate/quote range

-

when it must be paid (deposit vs final)

-

whether it’s required or optional

-

sales tax, shipping, installation, training

This table does two things:

-

It stops underborrowing caused by missing supporting costs.

-

It keeps you from overborrowing by exposing “nice-to-have” items that don’t affect results.

If a cost doesn’t directly support the loan’s purpose, it should be questioned before it’s financed.

3. Separate One-Time Costs From Ongoing Costs

Not all costs behave the same way. One-time costs happen once. Ongoing costs continue every month and can overlap with repayment.

One-time examples:

-

Equipment purchase

-

Renovation

-

Initial inventory build

Ongoing examples:

-

Software subscriptions

-

Higher rent or utilities

-

Ongoing marketing spend

If a loan funds ongoing costs, you must be certain that revenue will rise or expenses will fall enough to support those costs plus repayment. Otherwise, you are borrowing to cover a permanent gap.

4. Build a Timeline for When You Will Spend the Money

Timing matters as much as total amount. A project with costs spread over six months needs different planning than one that requires immediate full payment.

Create a simple timeline:

-

When each cost will hit

-

Whether vendors require deposits

-

When inventory must be paid for

-

When you expect revenue to start increasing

This timeline helps you avoid borrowing too early or too late. It also helps you choose the right loan type, since some loans release funds all at once while others allow drawdowns.

5. Estimate the Expected Return in a Conservative Way

A loan should not be based on best-case outcomes. Use conservative assumptions and give yourself room to be wrong.

For growth-focused borrowing, estimate:

-

Expected revenue increase

-

Expected margin on that revenue

-

Time required to reach that revenue

-

Costs required to maintain the new revenue level

If you’re buying equipment, estimate:

-

Capacity increase

-

Labor savings

-

Reduced waste or downtime

The goal is not to predict perfectly. The goal is to ensure the loan amount is justified by returns that still hold up when things move slower than expected.

6. Calculate What Monthly Payment Your Cash Flow Can Handle

This is the reality check. Your business may need a certain amount, but cash flow may only support a smaller payment.

Start with your average monthly net cash flow after essential expenses. Then stress test it.

Consider:

-

Your worst month in the last year

-

Delayed client payments

-

Seasonal dips

-

Rising costs that could return

A practical approach is to set a maximum safe repayment level that does not exceed a reasonable portion of your free cash flow. If repayment would force you to cut essentials or miss supplier payments, the amount is too high or the term is too short.

7. Add a Buffer Without Turning It Into Overborrowing

A buffer protects you from surprises. But a buffer should be intentional, not an excuse to borrow extra.

Common reasons for buffers:

-

Price changes in materials

-

Shipping delays and storage costs

-

Unexpected repairs or compliance costs

-

Slower ramp-up in sales

A buffer should be based on risk, not optimism. If your project is simple and costs are fixed, the buffer can be smaller. If your project depends on volatile pricing or uncertain timelines, the buffer should be larger but still tied to realistic scenarios.

8. Compare the Loan Cost Against the Business Impact

The final step is to test whether the loan cost makes sense relative to the value created.

Compare:

-

Total interest paid over the term

-

Origination fees and other charges

-

The opportunity created by the loan

-

The risk introduced by repayment obligations

If the loan’s total cost feels high, you may not need to abandon the plan. You may need to adjust the amount, extend the term, choose a different funding type, or reduce the project scope.

Why Loan Term Length Is Just as Important as Loan Size

Many business owners focus only on the loan amount and ignore the repayment term. This is a mistake. A shorter term reduces total interest but increases monthly pressure. A longer term lowers monthly strain but increases total cost.

The right loan amount only makes sense when paired with the right term. A $100,000 loan over five years may be manageable, while the same loan over two years may not be, even if the interest rate is lower.

Term length should match:

-

The useful life of what you’re funding

-

The speed at which the investment generates returns

-

Your revenue cycle and seasonality

If the loan outlives the value it created, the amount was wrong.

Common Signs You’re Borrowing Too Much or Too Little

You can often spot a wrong loan amount before you sign.

Signs you may be borrowing too much:

-

You cannot explain where a large portion of funds will go

-

Repayment requires perfect months to stay safe

-

You are borrowing to cover ongoing operating losses

-

You feel pressure to spend quickly to justify the loan

Signs you may be borrowing too little:

-

You are ignoring setup and supporting costs

-

You have no buffer for delays or price changes

-

You will run out of cash before the project pays back

-

You’ll need a second loan immediately after the first

The best loan amount is usually boring. It covers the plan, includes a buffer, and fits cash flow without drama.

A Clean Decision Framework: Three Numbers You Should Be Able to Defend

Before signing, you should be able to explain these three numbers clearly:

1) The Minimum Effective Amount

The smallest amount that fully completes the plan and achieves the purpose.

2) The Maximum Safe Payment

The payment your business can handle even during a weak month (based on your stress test).

3) The Risk-Based Buffer

The extra amount is tied to specific risks (not convenience spending). If you can defend these three numbers, your loan amount is no longer a guess—it’s a disciplined decision that protects operations.

Why Overestimating Growth Is the Most Common Borrowing Mistake

Optimism is natural when planning growth, but it becomes dangerous when used to justify borrowing. Many businesses assume growth will arrive faster than it does.

Common overestimation errors include:

-

Assuming immediate customer uptake

-

Underestimating sales cycles

-

Ignoring operational bottlenecks

-

Overlooking learning curves for new hires

A safer approach is to size the loan so it still works if growth is delayed. If the loan only works when everything goes right, the amount is too high.

What This Means for Right Loan Amount for Your Business

Borrowing can be a smart growth tool when it is planned with discipline. The right loan amount for your business is not your maximum approval. It is the amount that funds a specific outcome, pays back through realistic returns, and stays manageable even in weak months. When you treat the loan amount as a calculation rather than a guess, you protect your cash flow and increase the odds that borrowing actually improves your business.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Here are the most frequently asked questions among readers:

Should I Borrow the Maximum Amount a Lender Offers?

Not automatically. Lenders approve based on risk models, not on what is best for your operations. Borrow based on your plan and cash flow capacity.

How Do I Calculate a Buffer Without Overdoing It?

Base the buffer on realistic risks such as price changes, delays, and extra fees. Avoid adding a buffer just because you want extra cash available.

Is It Smart to Use a Loan for Marketing?

It can be if the channel is proven and you can track return. Borrowing for untested marketing is risky because the payoff is uncertain.

What If My Revenue Is Seasonal?

Seasonality changes what your business can safely repay. Use your lowest months to stress test repayment and consider a term that matches your cycle.

Can I Combine Multiple Funding Sources Instead of One Loan?

Yes. Some businesses mix a smaller loan with vendor terms, customer prepayments, or a credit line. This can reduce pressure and improve flexibility.