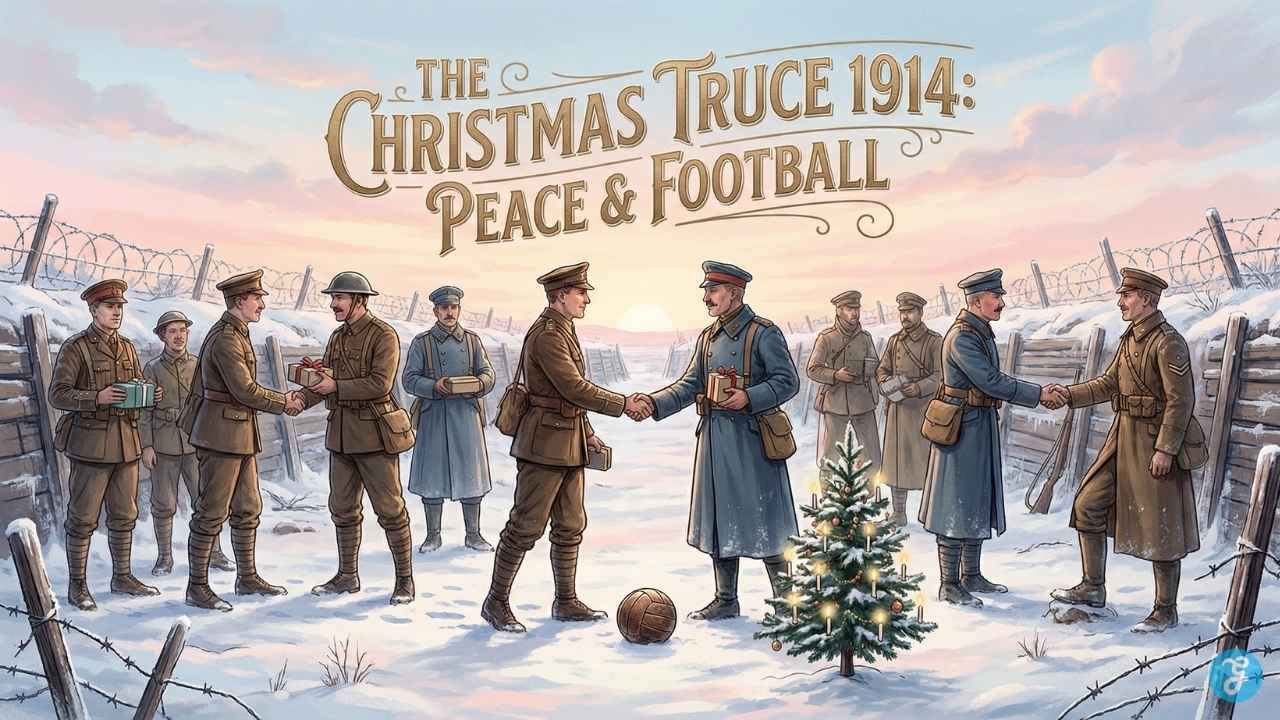

The Christmas Truce of 1914 is one of the most remarkable and most misunderstood episodes of World War I. For a brief moment during the first winter of the war, along certain sections of the Western Front, enemy soldiers stopped shooting, climbed out of their trenches, and met in No Man’s Land. They exchanged greetings, shared small gifts, helped recover and bury the dead, and, according to many accounts, some even kicked around a football. It didn’t end the war, and it didn’t happen everywhere, but it revealed something unforgettable: even in a conflict defined by fear and destruction, ordinary people could still recognize the humanity in the person on the other side.

This story gets retold every December for a reason. It’s dramatic, emotional, and easy to picture: carols drifting over the mud, flickering candlelight in the darkness, and cautious footsteps on ground that was usually a killing zone. But the real history is more complex than the legend—and understanding that complexity makes the truce even more powerful.

Key takeaways

-

The Christmas Truce of 1914 was unofficial and uneven, happening in some sectors while fighting continued in others.

-

It often began with carols, lights, and shouted greetings across trench lines.

-

The most consistent activity described in accounts was the chance to recover bodies and bury the dead.

-

Gift exchanges and short conversations were common in places where soldiers met.

-

Football likely occurred in some areas as informal kickabouts, but the idea of one organized, front-wide match is usually overstated.

-

Commanders were wary of fraternization, and the war’s escalation made repeats less likely.

Quick facts about the Christmas Truce of 1914

| Topic | Summary |

|---|---|

| When | Mainly December 24–25, 1914 (some local pauses lasted longer) |

| Where | Parts of the Western Front, especially sectors where opposing trenches were close |

| Who | Primarily British and German troops in many of the most-cited incidents (varied by sector) |

| What happened | Singing, greetings, meetings in No Man’s Land, gift swaps, burials, photos |

| Was it official? | No—local, spontaneous, and often discouraged afterward |

| Why it matters | A rare moment of empathy and shared humanity in modern industrial war |

What was the Christmas Truce of 1914?

The Christmas Truce of 1914 wasn’t a single, perfectly coordinated ceasefire across the entire front. It was a series of local, informal truces that appeared in patches, sometimes lasting a few hours, sometimes stretching into Christmas Day, and in a few places lingering beyond.

This matters for one big reason: the truce was not a planned peace agreement. It didn’t involve diplomats. It wasn’t a signed deal. It emerged from soldiers themselves, young men living in brutal conditions who, for a short time, responded to the season in a human way.

In many of the best-known incidents, troops stopped firing and began communicating across the lines. That communication could be cautious at first: a shouted greeting, a joke, a song. But in some areas, it developed into actual meetings between enemies who had been trying to kill each other only hours earlier.

Where it happened—and where it didn’t

It’s tempting to imagine the entire Western Front falling quiet, but the reality was mixed. In some areas, the lines were too active or too dangerous for any pause. Some units were involved in aggressive operations. Some commanders were strict. And sometimes the level of distrust was simply too high.

Where the truce did occur, it was often in sectors that had settled into a tense routine—places where men had been staring at each other across a relatively stable stretch of front and had developed an unspoken sense of “we both want to survive tonight.”

Life in the trenches before the truce

To understand why the truce stands out, it helps to understand what trench life felt like in late 1914.

The war that began with movement had turned into a grinding stalemate. Soldiers lived in muddy dugouts and narrow trench lines carved into the earth. They faced constant threats: snipers, artillery, raids, disease, and the mental pressure of never knowing when the next shell would hit. Rats and lice were common. Sleep was scarce. Fear became routine.

Christmas arrived in the middle of this reality. For many soldiers, it was their first Christmas away from home. Letters and parcels arrived from families. Some units tried to improvise small celebrations with whatever they had—tea, a bit of food, a shared joke, a borrowed moment of warmth.

And then something surprising happened: in some places, the men across the line did the same.

The “live-and-let-live” pattern

In certain quiet sectors, a kind of unofficial rhythm sometimes formed long before Christmas: predictable firing, mutual restraint at certain hours, a sense that pointless aggression could trigger retaliation. This wasn’t friendship—it was survival logic. But it created a fragile environment where a short pause at Christmas could become possible.

How the Christmas Truce of 1914 began

Most versions of the story start with sound: singing across the darkness.

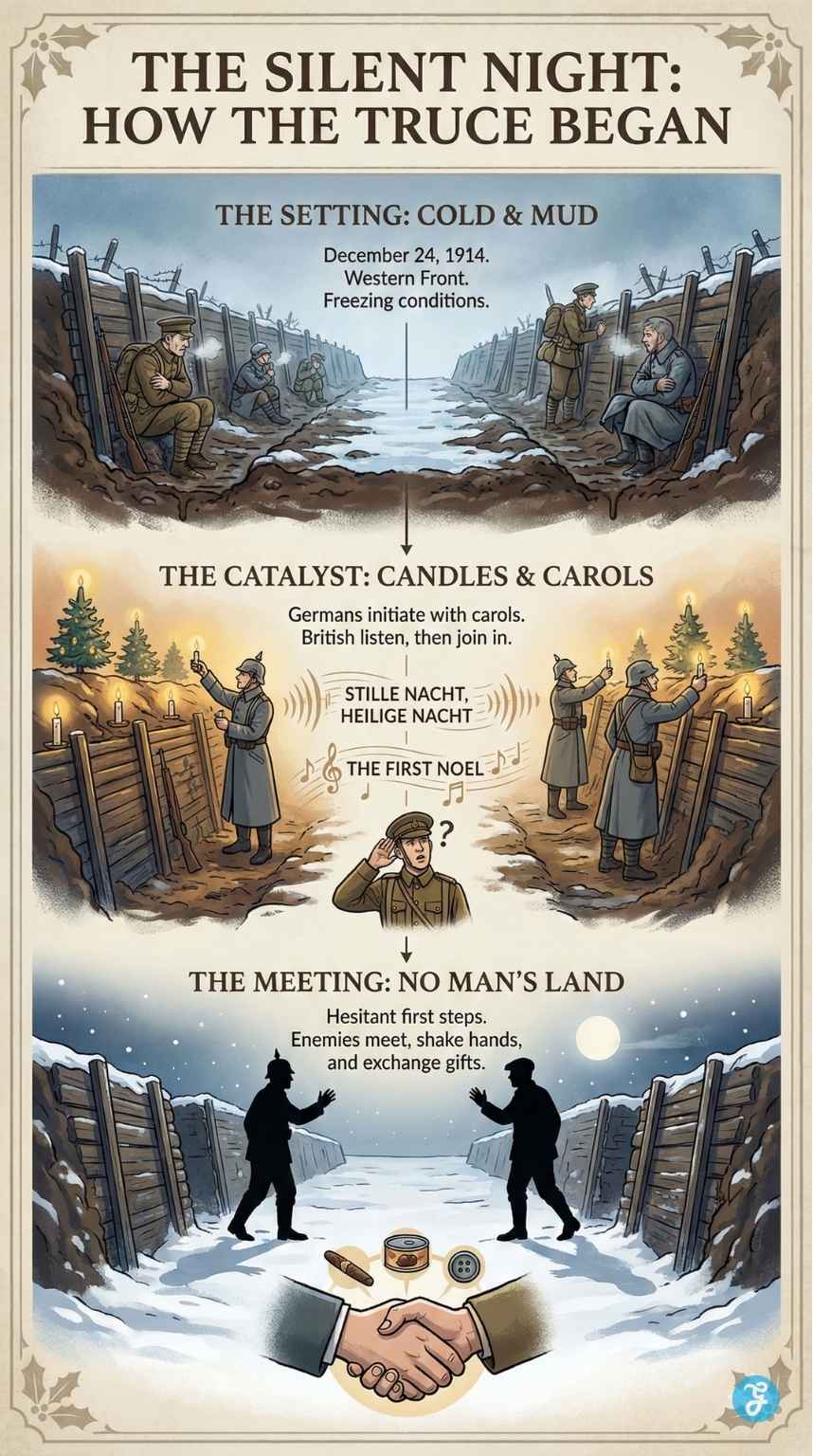

Carols, lights, and greetings across the trenches

On Christmas Eve, troops in some areas reported hearing singing from the opposing trenches. The most famous carol associated with the event is “Silent Night,” known across languages and cultures. In certain sectors, soldiers placed lanterns, candles, or small trees along their trench edges—tiny signs of celebration in a landscape built for killing.

Soon after, greetings were shouted across No Man’s Land. Some men called out “Merry Christmas.” Some responded. Others waved. In the darkness and cold, the space between the trenches became something else—not safe, but not immediately deadly.

Silent Night: Beginning of The Christmas Truce

By December 1914, the war was only five months old, but the “adventure” promised to young recruits had already turned into the nightmare of trench warfare. The armies were deadlocked in the freezing mud of Flanders, separated by a “No Man’s Land” often no wider than a swimming pool.

On Christmas Eve, the weather turned sharp and frosty, hardening the liquid mud into solid ground. It was the Germans who broke the silence. Along the lines near Ploegsteert Wood (known as “Plugstreet” to the British) and Wulverghem, British sentries saw small lights flickering on the enemy parapets. The Germans were placing Tannenbaum (small Christmas trees) lit with candles along their trenches.

Then came the sound. A rich baritone voice drifted across the frozen wire, singing Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht. The British troops, stunned, listened in silence before responding with The First Noel.

Sergeant Frank Naden of the 6th Cheshire Regiment recalled the surreal atmosphere:

“One German came out of the trenches and held his hands up. Our fellows immediately got out of theirs, and we met in the middle, and for the rest of the day we fraternised, exchanging food, cigarettes, and souvenirs.”

When soldiers met in No Man’s Land, they didn’t suddenly become best friends. They were still enemies in a war. But for a brief time, they behaved like people meeting people rather than targets meeting targets.

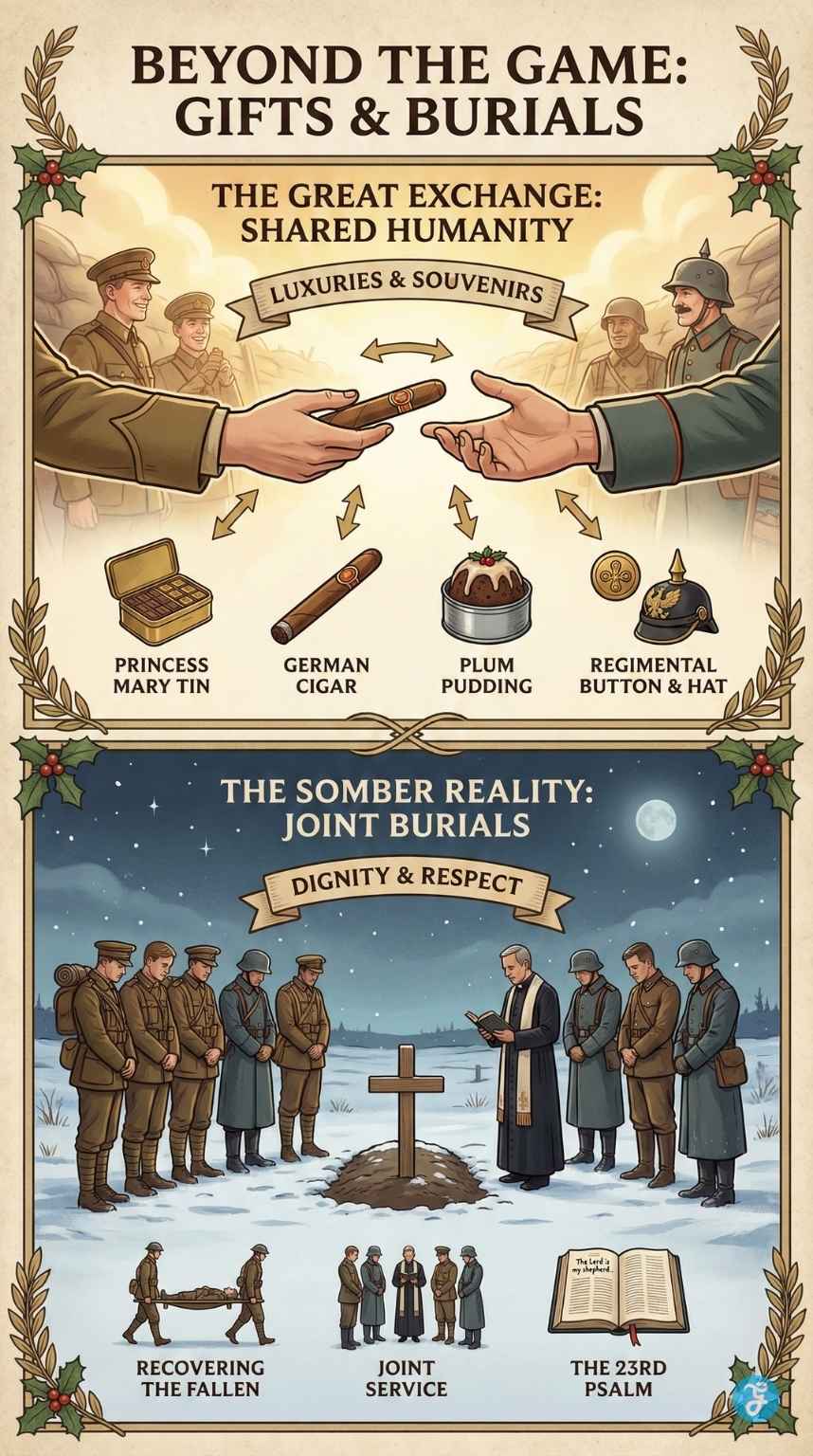

Recovering bodies and burying the dead

One of the most consistent and practical reasons the truce mattered was the chance to deal with the dead. Bodies could lie for days or weeks in exposed ground, impossible to recover under fire.

During parts of the truce, soldiers helped arrange burials or at least the recovery of bodies. It wasn’t always sentimental. Often it was simply necessary. But in the middle of a war where death had become constant, the act of giving the dead a basic dignity was powerful.

For many historians and careful retellings, this is the center of the truce story—not football, not gifts, but the way the pause allowed men to respond to death like human beings instead of numbers.

The Great Exchange

Soldiers bartered like old merchants. The Germans, often better supplied with luxuries, offered cigars and sausages. The British traded their “Bully Beef” (corned beef) and jams.

-

Princess Mary Tins: Many British soldiers had just received a brass gift tin from Princess Mary containing chocolate and tobacco. These became prized souvenirs for German soldiers.

-

Buttons and Hats: Soldiers swapped regimental buttons and even hats. A German Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) was the ultimate souvenir for a Tommy.

These weren’t expensive gifts. They were symbolic. In a war defined by propaganda and distance, the exchanges created a brief closeness.

Conversations across language and culture

Many soldiers spoke only a little of the other side’s language, but they still talked. Some used gestures and laughter. Some knew enough to exchange names, ask where someone was from, or describe hometowns.

These moments were often awkward and brief. That awkwardness makes them feel real. It wasn’t peace in a grand sense—it was a short recognition that the person across the line was also cold, hungry, and thinking of home.

Photos and mementos

In some areas, soldiers posed for photographs or collected small objects from the encounter. The existence of photos and personal keepsakes helped turn the truce into a lasting memory.

The Football Match: Myth vs. Reality

The most enduring image of the Christmas Truce 1914 is the football match. The popular story tells of a fully organized game, Germany vs. England, ending in a 3-2 victory for the Germans. While this specific “3-2” story is likely a myth or a conflation of rumours, football did play a central role in the truce.

Historians have found diary entries and letters confirming that while there wasn’t a “World Cup” style match, there were numerous “kickabouts.” These weren’t 11-a-side games with referees; they were chaotic melees involving dozens, sometimes hundreds, of men chasing a ball in heavy winter coats.

The Reality of the Game

Lieutenant Johannes Niemann of the Saxon 133rd Regiment provided one of the most credible accounts. He described a match against Scottish troops (likely the Seaforth Highlanders or Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders):

“A Scot produced a football… and a regular football match developed, with caps put down to mark the goals. The frozen ground was no problem. One of us had a camera… Quickly the footballers formed up into a single colorful group with the football at the center.”

It wasn’t just regulation leather balls, either. In sectors where no ball could be found, soldiers improvised. They kicked around empty tins of bully beef, or sandbags stuffed with straw and tied with string. The “score” didn’t matter. The act of playing—of engaging in a shared, playful human ritual in the middle of a slaughterhouse—was the victory.

Why the football detail became the headline

Football became the symbol for a simple reason: it’s easy to visualize. A football in No Man’s Land feels like the clearest possible contrast between war and peace. It turns a complicated set of local ceasefires into one powerful image.

But if you’re writing this story well, football should be framed as one possible element—not the whole event. The truce was also about singing, burial parties, gift exchanges, and brief human contact.

Myth vs reality: clearing up common misconceptions

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| “The whole Western Front stopped fighting.” | The truce was patchy. Some areas paused; others kept fighting. |

| “It was an official ceasefire.” | It was unofficial, driven by soldiers on the ground. |

| “There was one famous football match with a clear score.” | Football likely happened in some places as informal play; the tidy ‘official match’ narrative is often overstated. |

| “The truce proved the war could have ended right there.” | It showed shared humanity, but military strategy, politics, and escalation continued driving the conflict. |

| “Everyone involved felt the same way.” | Reactions varied—some men embraced the pause, others refused, and many returned to fighting with mixed feelings. |

The End of the Truce

The peace could not last. The truce was strictly unofficial, driven by the rank-and-file soldiers and junior officers. When news reached the High Command, the reaction was explosive.

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, a senior British commander, was furious. He issued strict orders that “friendly intercourse with the enemy” was forbidden, fearing it would destroy the “offensive spirit” needed to win the war.

By Boxing Day (December 26th), the truce began to dissolve. In some sectors, it ended with a mutual signal. Captain Charles Stockwell of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers described firing three shots into the air and raising a “Merry Christmas” flag. The German captain opposite him bowed, fired two shots in return, and the war resumed.

By 1915, the war had changed. The introduction of poison gas and the sheer scale of casualties hardened hearts. Heavy artillery bombardments were ordered on subsequent Christmas Eves to ensure the silence—and the singing—never happened again.

A simple timeline view

| Time | What often happened |

|---|---|

| Christmas Eve | Singing and greetings across the trenches; firing slows in some sectors |

| Late night | Cautious signs of trust—waving, calling out, small meetings |

| Christmas Day | Exchanges, burials, occasional informal games; photos in some places |

| After Christmas | Orders tighten; many units resume hostilities, sometimes reluctantly |

Voices from the Trenches: Real Letters Home

The most powerful evidence of the Christmas Truce 1914 comes not from history books, but from the penciled scribbles in the diaries of the men who were there. These accounts provide the undeniable proof that this “impossible” peace really happened.

Rifleman J. Reading of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment wrote to his wife about the surreal nature of the day:

“The Germans came out of their trenches and we did too. We crammed the space between the trenches… I had a conversation with a German who could speak English. He said he was tired of the war and wished it was over. We exchanged cigarettes and I gave him some buttons off my tunic.”

Captain Sir Edward Hulse of the Scots Guards described a moment of pure comedy amidst the tragedy in his letters. He organized a sing-song with the Germans:

“They finished their carol and we thought that we ought to retaliate, so we sang ‘The First Noel’, and when we finished that they all began clapping. And so it went on. I don’t think we have ever sung so well!”

These letters reveal a crucial truth: the soldiers didn’t see “monsters” across the field—they saw mirror images of themselves, bored, cold, and longing for home.

Why did the peace end

The Christmas Truce of 1914 was fragile. It existed in the gap between what soldiers felt and what armies required.

Commanders feared fraternization

War depends on clear enemy images. If soldiers see the enemy as human, it can weaken aggression and discipline. Leaders understood that. Even if some officers tolerated the pause for practical reasons—like burying bodies—most commanders did not want friendly meetings to become a pattern.

The war escalated

As World War I continued, it became more brutal and more controlled. Artillery increased. Large offensives came. Casualties mounted. The front hardened. Under those conditions, spontaneous ceasefires became harder to start and easier to punish.

The Christmas Truce became famous partly because it occurred early, before years of losses made the emotional distance between enemy troops even larger.

Why the Christmas Truce of 1914 still matters today

The truce endures because it challenges the simplest story war tells: that enemies are purely enemies. For one night, in certain places, soldiers demonstrated something that doesn’t fit the usual logic of battle. They showed restraint. They cooperated to bury the dead. They listened to songs from the other side. They spoke, laughed, and—possibly—played a bit of football.

It didn’t erase the war. It didn’t stop the killing that followed. But it revealed that the people inside the system of war were still capable of moral choice, even if only briefly.

In modern remembrance and commemoration, the truce often becomes a symbol of peace. A good article doesn’t turn it into a fairy tale. Instead, it treats it as a human story inside a harsh reality: a pause that was real, limited, and astonishing precisely because it was so difficult.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Christmas Truce of 1914

1) Was the Christmas Truce of 1914 real?

Yes, it was real. Multiple firsthand accounts describe temporary ceasefires and meetings between enemy soldiers along parts of the Western Front. What’s sometimes exaggerated is the scale—many areas never stopped fighting, and the truce looked different from one sector to another.

2) Did the Christmas Truce happen everywhere on the Western Front?

No. It was local and uneven. Some units experienced a genuine pause with meetings in No Man’s Land, while other sectors remained active and dangerous. The truce depended on immediate conditions, leadership attitudes, and how close the trench lines were.

3) What did soldiers actually do during the truce?

In sectors where it occurred, soldiers often exchanged greetings, sang carols, swapped small gifts like cigarettes or food, and used the pause to recover and bury the dead. Some posed for photos or collected small mementos. The tone ranged from cautious to surprisingly friendly, but it was rarely “perfect peace.”

4) Did they really play football in No Man’s Land?

In some places, accounts suggest they did—most likely as informal kickabouts rather than a fully organized match. The famous “one big football game with a clear score” is usually a simplified version of a messier reality. Still, even a brief kick-around in that setting is extraordinary.

5) Who won the Christmas Truce football match?

There was no single “official” match, so there was no official winner. The famous score of “3-2 to Germany” appears in some letters and stories, but it likely refers to a specific, informal kickabout or is a later fabrication. Most games were chaotic play with no score kept.

6) Why didn’t the Christmas Truce happen again on the same scale?

Commanders discouraged fraternization, and the war escalated. As violence grew more intense and armies tightened control, spontaneous truces became harder to start and easier to stop. Over time, the conflict hardened attitudes and reduced the space for moments like the one in 1914.

Final Words: A Victory for Humanity

The Christmas Truce of 1914 remains compelling because it’s not a fantasy. It’s a real, imperfect pause that emerged in one of history’s harshest environments. It reminds readers that even when systems demand brutality, individuals can still choose a different response—if only for a night.

And that’s why this story continues to resonate: it doesn’t pretend war is easy to end. It shows, instead, how rare and precious a moment of humanity can be when everything around it is designed to destroy it.