Manoj Kothari’s death on January 5, 2026, after a cardiac arrest at age 67 shocked India’s cue-sports community and reignited a familiar public reaction: if a celebrated athlete and national coach can suffer a sudden cardiac emergency, then how safe is sport—really?

That reaction often blurs important medical distinctions. Kothari was not a teenage sprinter collapsing mid-race. In at least one widely circulated report, he had undergone a liver transplant roughly 10 days earlier—an important context because major surgery and post-transplant physiology can elevate cardiovascular risk in ways that don’t map neatly onto the public’s idea of “fitness.” But the deeper meaning of this moment isn’t about one diagnosis. It’s about systems: what sports organizations, venues, gyms, and federations do before a cardiac event and what they can do in the first critical minutes after one begins.

In 2026, Athlete Cardiac Health sits at the intersection of three forces:

- Mass participation is expanding, including among older adults who train hard.

- Elite youth sport is getting more intense and year-round.

- The science is clearer than ever that survival depends on preparation—especially rapid CPR and fast access to an AED.

Kothari’s legacy, in other words, may also become a prompt for India—and sports markets globally—to treat cardiac safety like a foundational infrastructure requirement, not an optional “medical add-on.”

How We Got Here: Sport’s Risk Profile Quietly Changed?

For decades, the public assumed athletic activity was a near-universal shield against heart emergencies. The truth is more nuanced: regular exercise reduces long-term cardiovascular risk for most people, but high-intensity exertion can trigger dangerous rhythms or ischemic events in a small subset—especially when underlying disease is undetected or when short-term stressors stack up (recent illness, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, sleep loss, stimulant use, or major surgery).

Two long arcs brought us to today.

The first arc is demographic. Sport is no longer a young person’s arena. “Masters” competitions, endurance events, high-intensity gyms, and late-life athletic identities are growing fast. This expands the pool of people exposed to exertion at ages where coronary artery disease, hypertension, and metabolic risk are more common.

The second arc is organizational. Sports are professionalizing in markets where emergency medical standards vary wildly between elite centers and grassroots venues. A top stadium may have a tight emergency protocol and AEDs; a district tournament, academy, gym, or training hall may not. That gap matters because sudden cardiac arrest is a minutes game.

Here is the crucial framing for readers: screening tries to prevent events; emergency readiness determines survival when prevention fails.

| What The System Can Control | Examples | The Real-World Impact |

| Risk Detection | Pre-participation screening, symptom education, follow-up cardiology pathways | Reduces the number of “surprise” emergencies |

| Risk Reduction | Safe training progression, return-to-play rules, medication review, hydration/heat protocols | Lowers trigger likelihood |

| Survival After Collapse | Emergency action plans, CPR-trained staff, AED access, EMS coordination | Converts potential deaths into survivable events |

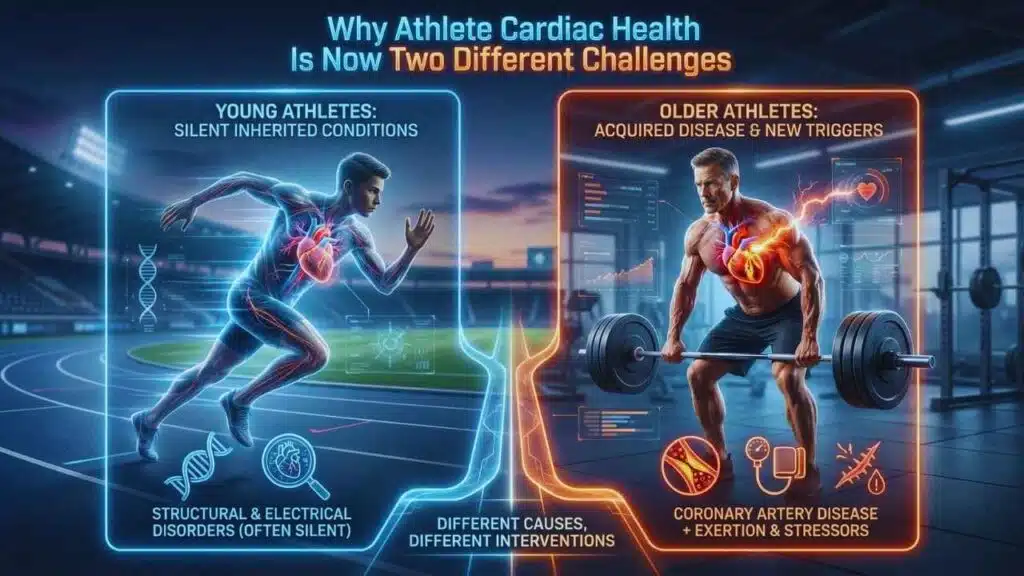

Why Athlete Cardiac Health Is Now Two Different Challenges?

One reason debates go in circles is that “athlete cardiac risk” is not one problem. It’s two overlapping ones—each with different dominant causes and different best interventions.

Young Competitive Athletes: Rare Conditions, Catastrophic Outcomes

In younger athletes, the fear is sudden collapse from inherited or congenital conditions that may be silent until exertion triggers an abnormal rhythm. These include structural and electrical heart disorders that sometimes do not produce warning signs.

Middle-Aged And Older Athletes: Common Disease, New Triggers

In older athletes, the dominant driver shifts toward acquired disease—especially coronary artery disease—plus risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, sleep apnea, and prior inflammation. The physiology of “being athletic” does not erase these risks, and intense exertion can become a trigger in susceptible individuals.

Kothari’s age places him closer to the second category. If the transplant detail reported by some outlets is accurate, it also underscores a third reality: athletic identity can persist through major health events, and the period after major surgery or illness is precisely when risk can be highest.

| Athlete Segment | Typical Dominant Risk | What “Better Safety” Looks Like |

| Teens / Young Adults | Silent inherited or congenital conditions | Smarter screening and sport-specific eligibility decisions |

| 35–60 | Mix of inherited and acquired risk | Risk-factor management + targeted testing for symptoms |

| 60+ / Post-Illness | High acquired risk, medication and recovery effects | Medical clearance, cautious progression, strong emergency readiness |

What The Numbers Actually Say: Risk Is Low, But Outcomes Are Preventable

Cardiac emergencies in sport are not common relative to the number of participants. But when they happen, the outcome is heavily influenced by response time and preparation—meaning many deaths are not “unavoidable fate,” but “systems failure.”

A few benchmark data points frequently cited in leading registries, clinical reviews, and resuscitation reporting help frame the issue:

- Global cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide.

- Sudden cardiac arrest survival improves dramatically when CPR begins quickly and an AED shock is delivered early.

- Even in high-resource settings, AED use by bystanders in public arrests remains low—suggesting a large, fixable gap.

| Indicator (High-Level) | What It Signals For Sport |

| Cardiovascular disease is the world’s top killer | Sport cannot treat cardiac risk as “rare” in the population |

| Survival drops sharply with each minute of delay | Venues must plan for the first 3–10 minutes |

| Bystander CPR and AED use remain below what’s needed | Training and access—not just hospitals—drive outcomes |

The practical conclusion: If sports bodies want to materially reduce preventable deaths, emergency readiness is the fastest lever, and screening is the longer-term lever.

Screening In 2026: Why The Old Arguments Are Being Replaced By A New Model?

The screening debate has historically been framed like a binary: ECG screening vs. no ECG screening. That framing is losing relevance.

Modern sports cardiology has moved toward a layered, risk-tiered approach:

- baseline history and physical evaluation

- targeted ECG use (where expertise exists to interpret it correctly)

- structured criteria that reduce false positives

- clear follow-up pathways for abnormal results

- different strategies for different age groups and sports

The reason this shift matters is simple: a test is only as good as the system behind it. Screening without expert interpretation and follow-up can produce anxiety, unnecessary disqualification, and wasted costs. But screening with modern criteria and proper pathways can detect meaningful risk earlier.

| Screening Model | What It Typically Includes | What It Optimizes | Common Weak Point |

| Minimalist | Questionnaire + exam | Cost and ease | Misses silent conditions |

| ECG-Inclusive (Where Supported) | History + exam + ECG + defined follow-up | Higher detection of electrical red flags | Needs trained interpretation capacity |

| Tiered By Age And Sport | Different protocols for youth vs. adults vs. older athletes | Matching risk to reality | Requires governance maturity |

A reader-friendly way to think about it: screening reduces risk, but it does not eliminate it. That’s why “screening-only” policies often disappoint the public after the next incident.

The Most Underused Life-Saver: AED Access And Rehearsed Emergency Action Plans

If screening is about prevention, emergency planning is about survival. And survival is where sport can improve quickly.

In sudden cardiac arrest, the heart often enters a shockable rhythm early on. CPR keeps blood flowing; an AED can restore a normal rhythm. This is why major sports bodies increasingly treat AED presence, rehearsed emergency action plans, and trained responders as essential.

Yet in many settings—especially outside elite stadiums—gaps remain:

- AEDs are absent, locked, or difficult to locate

- staff are untrained or hesitant to act

- emergency roles are unclear

- EMS response is not integrated into the venue plan

| Emergency Readiness Element | What “Good” Looks Like | What Fails In Practice |

| AED Availability | Visible, accessible, maintained, mapped | Locked away, unmaintained, unknown location |

| Training | Coaches/staff certified, refreshed annually | “Someone else will handle it” culture |

| Emergency Action Plan | Written, rehearsed, role-based | No plan, confusion, delayed CPR |

| EMS Integration | Clear address, entry points, call protocol | Ambulance delay, wrong gate, no guide |

The uncomfortable truth: For many venues, the difference between tragedy and survival isn’t a million-dollar hospital. It’s a two-minute decision by a trained person who knows where the AED is.

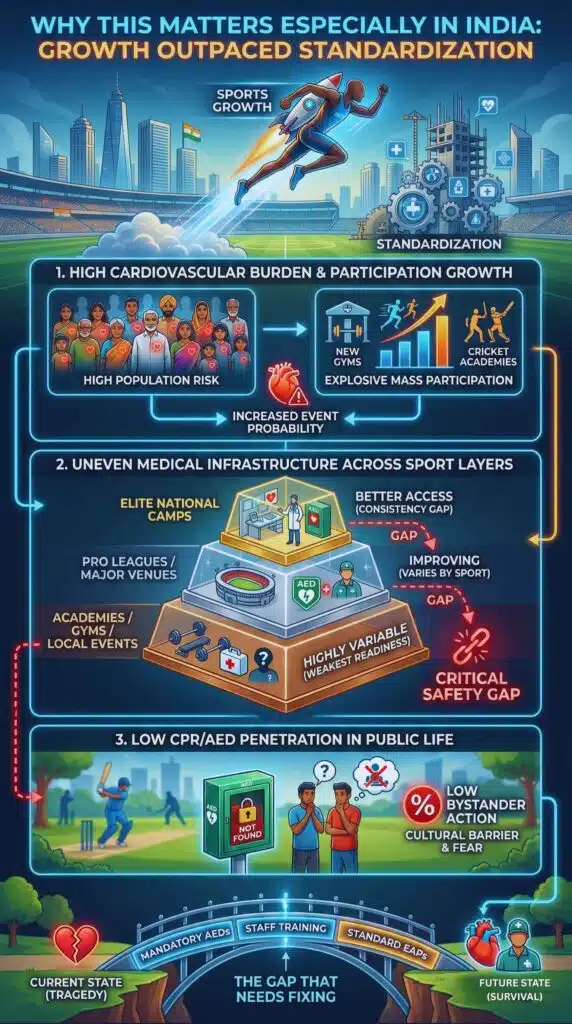

Why This Matters Especially In India: Growth Outpaced Standardization?

India’s sports economy and fitness culture have expanded quickly: more academies, more leagues, more gyms, more endurance events, and more “serious amateurs.” This is a positive national story—but it creates a safety challenge when governance and medical readiness don’t scale at the same rate.

Three India-specific dynamics make Athlete Cardiac Health a priority topic:

High Cardiovascular Burden Meets High Participation Growth

India carries a heavy load of cardiovascular risk factors at population scale. Even if athletic activity reduces risk for many, the base rate remains high enough that events will occur in active populations.

Uneven Medical Infrastructure Across Sport Layers

Elite national camps and major venues are not the problem. The vulnerability sits in the mid- and lower-tier ecosystem: district competitions, private academies, local tournaments, and everyday gyms.

Low CPR/AED Penetration In Public Life

In many places, CPR training is not normalized, AEDs are uncommon, and fear of “doing it wrong” keeps bystanders from acting. That cultural barrier directly influences survival.

| Layer Of Sport | Typical Medical Readiness | The Gap That Needs Fixing |

| Elite National Camps | Better access to sports medicine | Consistency and auditing |

| Pro Leagues / Major Venues | Improving, but varies by sport | Standard AED + training mandates |

| Academies / District Events | Highly variable | Basic emergency plan + AED access |

| Gyms / Recreational Settings | Often weak | Minimum standards + staff CPR training |

What Kothari’s Case Also Signals: “Athlete” No Longer Means “Low Risk”

Kothari’s role matters here. He wasn’t only an athlete; he was a coach and mentor—someone likely embedded in sport as a lifelong identity. This is increasingly common: former athletes and long-time coaches remain active, travel frequently, face stress, and may prioritize performance culture over medical caution.

This creates a new policy and education need: cardiac safety messaging must target older participants and leadership figures, not just youth athletes.

| Common Assumption | What The Evidence-Based View Suggests |

| “Athletes don’t have heart problems.” | Athletes can have silent or acquired disease; risk varies by age |

| “Screening prevents all deaths.” | Screening reduces risk but cannot eliminate it |

| “Hospitals save lives.” | The first 3–10 minutes decide outcomes in many arrests |

| “Gym training is safer than sport.” | High-intensity training can be a trigger in susceptible individuals |

Different Viewpoints, One Practical Middle Ground

To stay neutral, it’s important to acknowledge reasonable disagreement.

Some experts emphasize broad screening expansion because detecting silent risk earlier feels like the most direct prevention tool. Others emphasize emergency response because it saves lives even when screening misses cases—and it scales faster.

Both camps are partly right. The “middle ground” that is gaining traction globally looks like this:

- Use tiered screening where interpretation and follow-up pathways exist

- Improve symptom awareness and referral pathways everywhere

- Treat AED access, CPR training, and rehearsed plans as universal minimums

| Viewpoint | Strongest Argument | Legitimate Concern |

| Expand Screening Aggressively | Detect silent risk earlier | False positives + uneven system capacity |

| Prioritize Emergency Readiness | Saves lives even when prevention fails | Doesn’t reduce event incidence as much |

| Tiered Hybrid Approach | Matches tools to risk + resources | Requires policy discipline and audits |

What Happens Next: The Likely Milestones To Watch In 2026?

Predictions should be labeled as such, but the direction is visible.

What Analysts Expect Sports Bodies To Move Toward?

- Minimum AED and CPR requirements for sanctioned competitions, leagues, and training centers

- Standardized emergency action plans as part of licensing/affiliation

- Greater differentiation by age in screening and medical clearance

- Stronger data collection and registries so policy is informed by patterns, not headlines

What The Fitness Industry Will Likely Face?

- More public pressure on gyms and event organizers to:

- keep AEDs on site

- train staff

- display emergency protocols

- encourage medical clearance for high-risk members

| 2026 Watchlist Item | Why It Matters |

| AED Requirements For Venues | Fastest path to improved survival |

| CPR Training Expansion | Converts bystanders into responders |

| Registry/Reporting Improvements | Turns anecdotes into actionable policy |

| Screening Pathway Upgrades | Reduces preventable “silent risk” events |

The Most Valuable Lesson From Kothari’s Legacy

Manoj Kothari will be remembered for what he built in Indian cue sports—titles, mentorship, and a lasting national imprint. But the wider lesson from this moment is not about cue sports alone. It’s about how the meaning of “athlete safety” is evolving.

In 2026, Athlete Cardiac Health is best understood as a complete chain:

- prevention where possible (smarter screening and risk-factor management)

- preparation everywhere (AEDs, CPR training, emergency plans)

- learning over time (registries and transparent reporting)

If sport treats that chain as standard infrastructure, fewer tragedies will feel preventable in hindsight.