On a cold February morning in 1952, students marched down the streets of Dhaka, their voices cutting through the morning air with a single demand: the right to speak in their mother tongue. Police opened fire. Young men fell. But the Bengali language did not. Seventy-four years later, Artificial intelligence—a technology that speaks no language of its own—has begun to look back at that defining moment.

What does it see? What can it truly understand? And more profoundly: can a machine honor what humans gave their lives to protect?

This feature explores a unique intersection of memory and technology—the growing trend of using AI image generators, large language models, and generative art platforms to visualize, narrate, and commemorate the Ekushey Language Movement of 1952. As Bangladesh prepares to observe International Mother Language Day on February 21st, we ask: does artificial intelligence get it right?

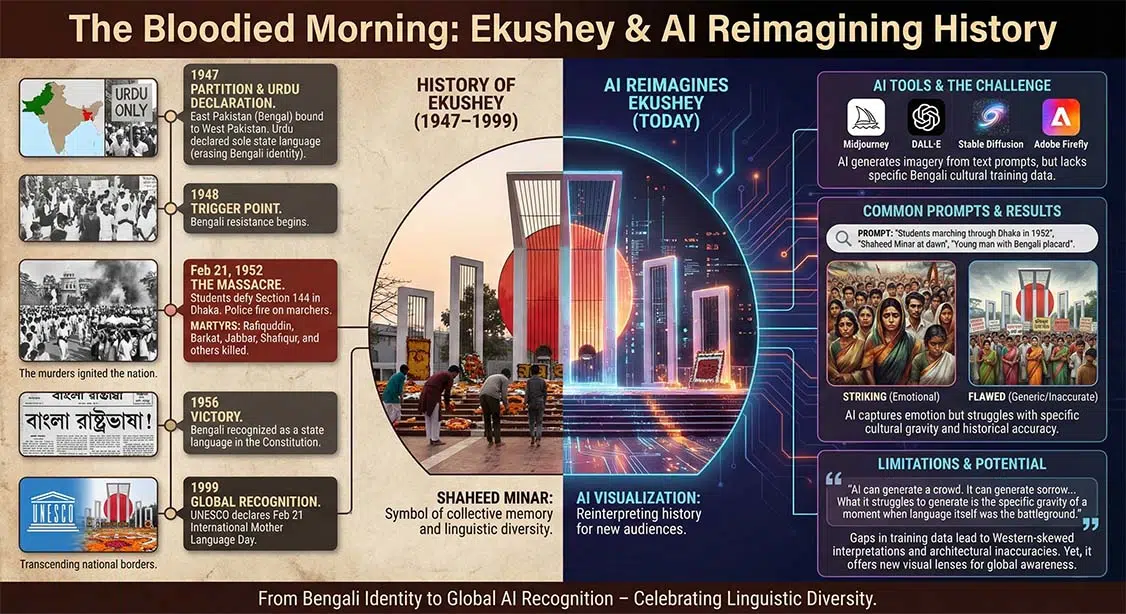

The Bloodied Morning: A Brief History of Ekushey

To understand what AI is recreating, one must first understand what actually happened. In 1947, when British India was partitioned into India and Pakistan, the newly formed East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) found itself bound to a state whose West Pakistan-based government had declared Urdu—a language spoken by fewer than 10% of Pakistan’s total population—as the only official state language. For the 56 million Bengali speakers of East Pakistan, this was not merely a political decision. It was an erasure of identity.

The resistance was immediate and fierce. By February 1952, university students, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens in Dhaka had organized mass demonstrations. On the morning of February 21st, defying a government-imposed Section 144 that banned gatherings, thousands of students from the University of Dhaka and Dhaka Medical College marched towards the East Bengal Legislative Assembly. The police response was swift and brutal. Rafiquddin Ahmed, Abul Barkat, Abul Jabbar, Shafiqur Rahman, and several others were shot dead. Hundreds more were wounded and arrested.

The murders did not silence the movement. They ignited it. Within days, the entire nation was in revolt. The martyrs became immortal. In their honor, the Shaheed Minar—the Martyrs’ Memorial—was erected at the site of the killings, and every February 21st since, Bangladeshis walk barefoot to that monument before dawn, laying flowers in an act of collective memory that has endured for over seven decades.

In 1999, UNESCO recognized the date as International Mother Language Day, enshrining February 21st as a global occasion to celebrate linguistic diversity and protect endangered languages. The Language Movement had transcended national borders. And now, in the age of AI, it has transcended human artistry.

| Date / Event | What Happened |

| February 21, 1952 | Police open fire on student protesters near Dhaka University, killing Rafiquddin Ahmed, Abul Barkat, Abul Jabbar, Shafiqur Rahman, and others. |

| 1948 – Trigger Point | The Pakistan government declares Urdu as the sole state language, igniting Bengali resistance. |

| 1952 – Mass Mobilisation | Students and citizens defy Section 144, rallying under the slogan ‘Rashtrobhasha Bangla chai’ (We want Bengali as a state language). |

| 1956 – Victory | Bengali was recognized as one of Pakistan’s state languages in the new Constitution. |

| 1999 – Global Recognition | UNESCO declares February 21 as International Mother Language Day. |

| Today – AI Remembers | Artificial intelligence platforms visualize and narrate the Language Movement for new global audiences. |

AI Picks Up the Brush: How Technology Reimagines History

In recent years, AI image generation tools—Midjourney, DALL·E, Stable Diffusion, and Adobe Firefly—have given millions of users the ability to generate photorealistic, painterly, or surrealist imagery from simple text prompts. Historians, educators, and artists have begun using these tools to visualize events for which no photographs exist or to reinterpret well-documented history through new visual lenses.

The 1952 Language Movement sits at a fascinating crossroads for these technologies. On one hand, there is substantial documented history: archival photographs, films, written testimonies, and decades of artistic interpretation in painting, poetry, and sculpture. On the other hand, the emotional and cultural weight of the event—the grief, the courage, the profound love for one’s mother tongue—presents a formidable challenge for any AI system trained primarily on Western datasets.

What Prompts Are People Using?

Online communities in Bangladesh and among the global Bengali diaspora have begun experimenting with AI art prompts related to Ekushey. Common prompts include descriptions of ‘students marching through Dhaka in 1952,’ ‘the Shaheed Minar at dawn covered in flowers,’ ‘a black-and-white crowd scene outside Dhaka University,’ and ‘a young man holding a Bengali alphabet placard.’ The results are often striking—and occasionally deeply flawed.

“AI can generate a crowd. It can generate sorrow etched on faces. What it struggles to generate is the specific gravity of a moment when language itself was the battleground.”

When asked to depict ‘the Ekushey massacre,’ most AI models produce generic protest imagery—crowds, police, colonial-era architecture—with little specificity to Bengali culture. The saris are sometimes wrong. The signage appears in incorrect scripts. The Shaheed Minar, one of the most recognizable structures in Bangladesh, is occasionally rendered with architectural inaccuracies. These gaps reveal the limitations of training data that skews heavily towards Western historical events.

Language Models and the Language Movement: A Textual Analysis

Beyond visual art, large language models (LLMs) like Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini have been asked to write poems, essays, historical narratives, and even school textbook entries about the 1952 Language Movement. The quality of the output reveals how well these models have absorbed Bengali history into their training corpora.

In tests conducted by digital educators in Dhaka, LLMs consistently identified the correct date of the massacre, named the primary martyrs, and described the broader political context of Pakistani language policy. When asked to write a poem about Ekushey, the models produced linguistically competent verse—sometimes in English, sometimes in translated Bengali—that captured the themes of sacrifice, identity, and resistance.

However, the outputs often lacked what Bangladeshi readers would call “aatma”—soul. The verse could describe a mother weeping for her son; it could not replicate the gut-wrenching intimacy of Abul Barkat’s mother, who reportedly never fully recovered from her grief. AI writes about the movement. It does not grieve with it.

| AI Output Sample—Poem on Ekushey (Generated via Claude, February 2026)

“They wrote with their blood on February streets, a grammar of sacrifice that textbooks could not teach. The alphabet became a flag, the flag became a wound, and the wound became a nation’s oldest song.” — AI-generated verse when prompted with: ‘Write a poem about the 1952 Bengali Language Movement in a literary style.’ |

The sample above demonstrates that AI can produce evocative writing on the subject. It uses historically resonant imagery—blood, alphabet, and flag—and captures the movement’s thematic core. Yet a Bangladeshi poet would likely find it slightly detached, as if observed from a satellite rather than from the road in front of Dhaka Medical College on February 21st.

The Shaheed Minar Problem: Can AI Understand Sacred Architecture?

Perhaps no single image is more central to Ekushey than the Shaheed Minar. Originally built in February 1952, just days after the massacre—and subsequently demolished by Pakistani authorities before being rebuilt and redesigned—the Martyrs’ Memorial is a curvilinear structure of white concrete that represents a mother sheltering her children. It is minimalist, profoundly symbolic, and instantly recognizable to every Bangladeshi.

When AI image generators are prompted to depict the Shaheed Minar, results vary dramatically. Midjourney and DALL·E often produce generic memorial structures—obelisks, arches, columns—that bear little resemblance to the actual monument. Some outputs show the correct curved white forms but set them in landscapes that could be anywhere. The context—Dhaka’s streets, the surrounding university buildings, and the blanket of white tuberose flowers that covers the monument every February 21st—is frequently absent.

This is not a trivial aesthetic failure. The Shaheed Minar is not merely a building. For Bangladeshis, it is a wound made into art, a site of annual mourning and annual renewal. When AI misrepresents it, the misrepresentation matters—because increasingly, international audiences may encounter AI-generated imagery of Ekushey before they encounter the real photographs, documentaries, or testimonies.

“The danger is not that AI imagines Ekushey incorrectly. The danger is that its incorrect imagination becomes the default image for those who have never had another.”

Where AI Gets It Right: Accessibility, Scale, and Multilingual Reach

It would be unfair — and inaccurate — to focus only on AI’s limitations in this domain. There are areas where the technology has made genuine, meaningful contributions to the preservation and dissemination of Ekushey’s legacy.

Making History Accessible to New Generations

AI-powered educational tools, chatbots, and interactive platforms have made it substantially easier for young Bangladeshis — and members of the global diaspora — to access detailed, accurate information about the Language Movement. A teenager in London or New York can now ask an AI assistant about Ekushey and receive a comprehensive, nuanced response in seconds.

This democratisation of historical knowledge is not trivial. Before these tools, accessing detailed English-language content about the 1952 movement often required academic databases or specialised books.

AI Translation: The Language Movement in Every Language

There is a beautiful irony in using AI translation technology — itself a study in the mechanics of language — to spread awareness of the Language Movement to non-Bengali audiences. AI translation tools like Google Translate and DeepL now produce high-quality translations of Bangladeshi historical texts, academic papers about the movement, and even Bengali poetry into dozens of languages. The struggle to protect one language is now told in hundreds.

Generative Art as a Teaching Tool

Some Bangladeshi educators and NGOs have begun using AI-generated imagery as a starting point for classroom discussions rather than as a final product. When students see an AI-generated depiction of the 1952 protests and immediately notice what is wrong — the incorrect script on the placards, the non-Bengali clothing, the absent Shaheed Minar — it sparks critical thinking about how history is represented, who controls those representations, and what is lost when memory is delegated to algorithms.

Bengali Artists Respond: Taking Back the Canvas

The rise of AI art has prompted a robust creative response from Bengali artists. Painters, illustrators, digital artists, and graphic designers in Dhaka, Chittagong, and the diaspora communities of the UK, USA, and Canada have used Ekushey as a rallying point — producing human-made art that explicitly situates itself in opposition to, or in dialogue with, AI-generated imagery.

Several notable Bangladeshi illustrators have published social media threads directly comparing their hand-drawn Ekushey art with AI versions of the same scenes, highlighting the differences with detailed commentary. The contrast has proven striking: the human work is rich with cultural texture — the specific curve of a women’s phita (hair ribbon), the precise rendering of a dhunia (cotton screw) being worn as protest attire, the emotional specificity of faces shaped by decades of studying those historical photographs.

This artistic dialogue has produced something unexpected: AI’s imperfect attempt at Ekushey has reinvigorated human artistic engagement with the movement. By showing what a machine cannot feel, Bengali artists have been inspired to show what humans can.

“Let the machine try. When it fails, it teaches us something about what we carry inside us that no training data can replicate.”

The Ethics of Algorithmic Memory: Who Should Narrate History?

The use of AI to represent historical trauma raises profound ethical questions that are by no means unique to the Language Movement, but are made especially vivid by it. The massacre of February 21, 1952 is not a distant abstraction. Survivors are still alive. The families of martyrs still gather at the Shaheed Minar. The Movement is not historical in the way that, say, the Battle of Hastings is historical — it is living memory, transmitted generationally with great care and great pain.

When AI generates imagery or text about Ekushey without this context — without the knowledge that Abul Barkat’s family still visits his grave, that his sister reportedly never stopped wearing white after his death — it risks producing what scholars of digital humanities call ‘memory without grief’: the archive without the emotion that gives the archive its meaning.

There is also the question of whose AI we are talking about. The large language models and image generators currently available are predominantly built by American and European technology companies, trained on datasets that over-represent English-language and Western-historical content. A Bengali-language AI, trained on the full breadth of Bangladesh’s literary, historical, and cultural output, would presumably produce very different — and more culturally grounded — representations of Ekushey.

| Did You Know?

As of 2026, Bangla is the seventh most spoken language in the world by native speakers, with over 230 million speakers globally. Yet it remains significantly underrepresented in the training data of most major AI language models. Efforts to build Bangla-first AI models are underway at universities in Dhaka and at organisations like the Bangla Natural Language Processing (BanglaNLP) research initiative. |

This underrepresentation has practical consequences. When Bengali-language AI tools are asked to generate Ekushey-related content in Bangla itself, the quality is noticeably lower than equivalent outputs in English. Grammar can be awkward. Cultural references may be misused. The poetic traditions specific to Bengali literature — the Baul tradition, Rabindranath Tagore’s influence, the specific cadences of Mukherjee-era Bengali verse — are often absent. AI, for all its apparent fluency, does not yet speak Bengali the way Bengali wishes to be spoken.

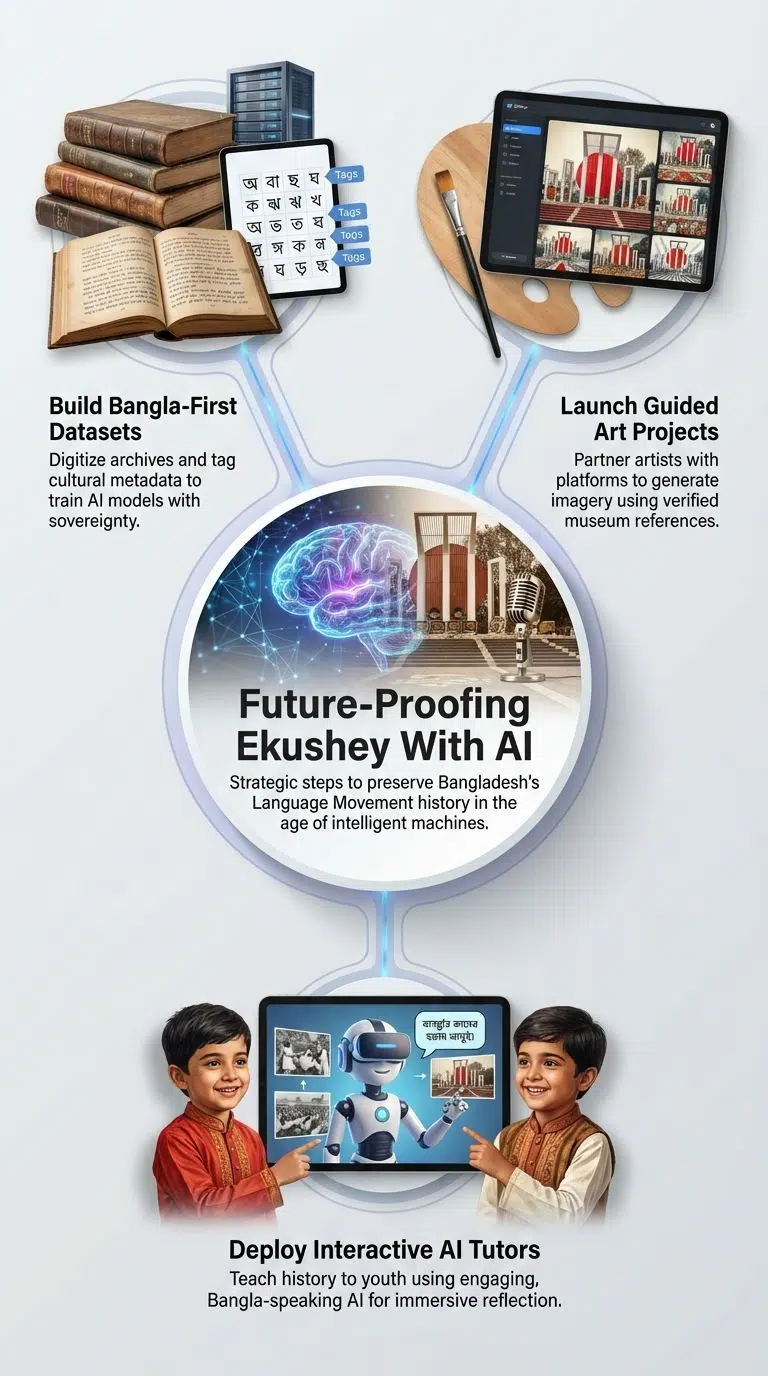

A New Ekushey for a Digital Age: What Should Come Next?

The conversation about AI and the Language Movement is not merely retrospective. It points towards the future of how Bangladesh — and all nations with histories of cultural struggle — will preserve and transmit memory in the age of intelligent machines.

Building Bangla-First AI Datasets

The most practical step that scholars, technologists, and government bodies in Bangladesh can take is to build comprehensive, culturally rich, Bengali-language datasets that can be used to train AI models. This means digitising the full archive of Language Movement testimonies, newspaper articles, memoirs, and photographs; tagging them with appropriate cultural and historical metadata; and making them available to AI researchers under terms that preserve cultural sovereignty.

Community-Guided AI Art Projects

Rather than allowing AI to generate Ekushey imagery in a vacuum, Bangladeshi artists and cultural institutions could partner with AI platforms to create guided image generation experiences: AI tools pre-trained on approved, historically accurate visual references from the Bangladesh National Museum, curated by cultural scholars, and available specifically for Ekushey-related prompts. The result would be AI imagery that is still generated, but generated responsibly — with human cultural oversight at every stage.

AI in Ekushey Education

Interactive AI tutors could be designed specifically to teach the Language Movement to young Bangladeshis in an engaging, age-appropriate way. Imagine an AI that can answer a ten-year-old’s questions about Rafiquddin Ahmed in Bangla, show them contextual imagery of 1950s Dhaka, play audio recordings of Ekushey poems, and then ask the child to reflect on what they would have done in 1952. This is not fantasy — the technology exists. What is required is the will to deploy it in service of memory rather than mere convenience.

Takeaways

Every February 21st before dawn, Bangladeshis from every walk of life — students, professors, rickshaw pullers, politicians, grandmothers — remove their shoes and walk barefoot to the Shaheed Minar. They carry white flowers. Many weep. The bare feet on the cold concrete are a physical act of connection: to the soil, to the martyrs, to the unbroken chain of memory that stretches from 1952 to the present day.

No AI will ever remove its shoes. No algorithm will ever feel the cold of that concrete, or be moved to tears by the Ekushey procession, or understand — not intellectually, but bodily — what it means to have your language taken from you and to fight to take it back.

And yet. AI is not nothing in this conversation. It is a mirror — imperfect, distorted, sometimes grotesquely wrong — that shows us something about our history by failing to reflect it perfectly. It is a tool that can carry the facts of Ekushey to a teenager in Toronto who might never otherwise encounter them. It is a canvas that can provoke Bengali artists to paint more deeply, more specifically, more lovingly than they might have without the provocation of a machine’s shallow imitation.

The 1952 Language Movement was fought so that Bengali could be spoken. Today, in 2026, Bengali is spoken by more than 230 million people. It is being translated by machines, generated by algorithms, and studied in universities worldwide. The martyrs of Ekushey could not have imagined any of this. But they understood, in the most fundamental way, what it means to insist that a language — and therefore a people — will not be erased.

“AI can be trained on a language. It cannot be born into one. The difference is everything. But it is also an invitation — to teach, to correct, to insist on our own telling of our own story.”

Painted by a machine, remembered by a nation. The canvas belongs to Bangladesh. The memory always will.