EU-China Renewable Energy Trade Barriers 2026 represent a fundamental shift in the global energy landscape, as the era of “unrestricted green globalization” officially concludes. For over a decade, the European Union’s transition to a low-carbon economy was powered by a steady stream of low-cost Chinese photovoltaic (PV) modules and wind turbine components.

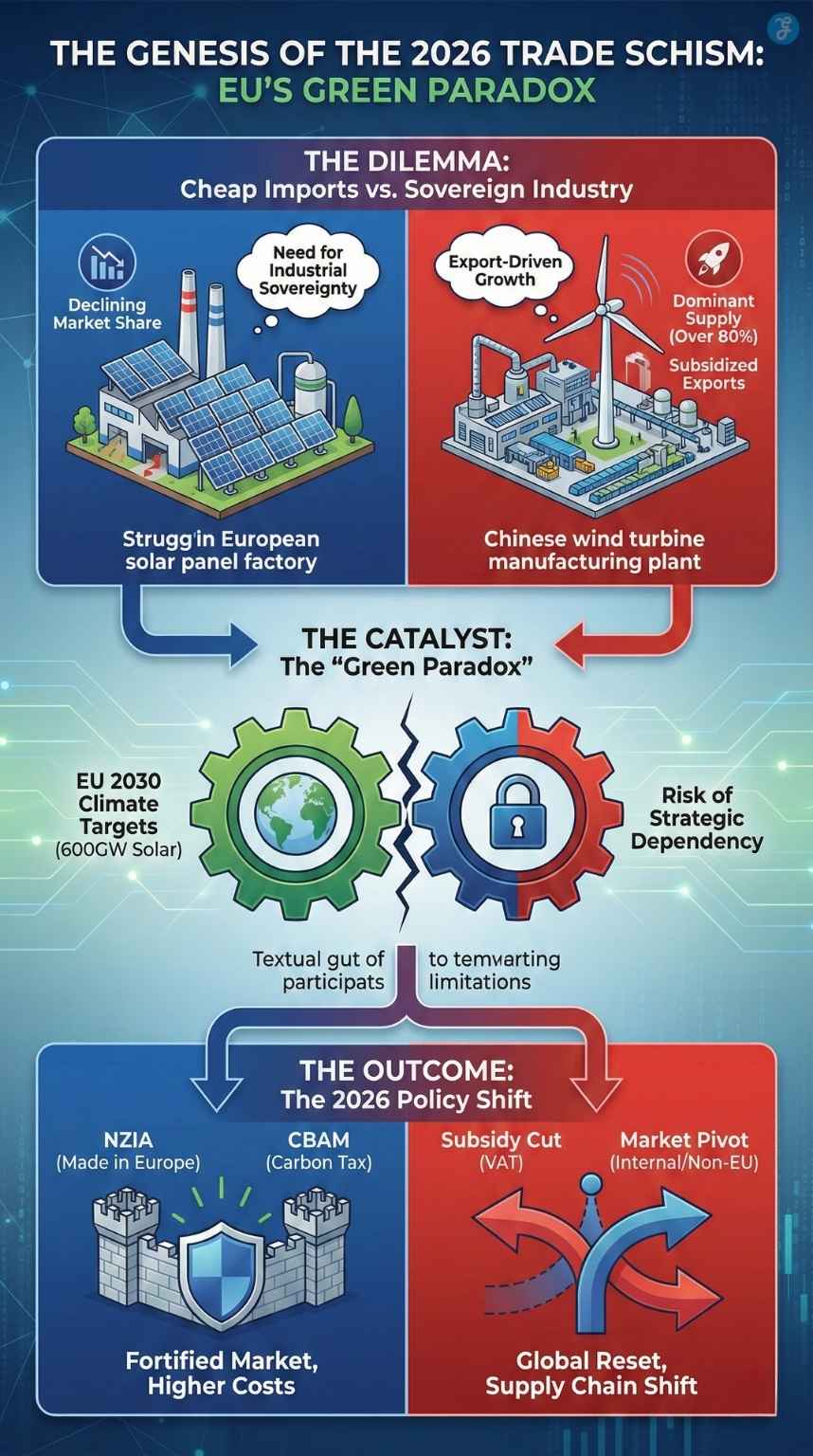

However, as of January 2026, the legislative frameworks designed to protect European industrial sovereignty have transitioned from theoretical policy to hard-hitting market reality. This year marks a definitive turning point. The implementation of the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), the activation of the definitive phase of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and a surprise move by Beijing to cut export tax rebates have combined to create a “perfect storm” for energy developers.

This in-depth analysis explores the multi-layered trade barriers redefining the renewable sector in 2026 and what they mean for the future of the Green Deal.

Key Takeaways: EU-China 2026 Trade Barriers

- NZIA Enforcement: Public tenders now mandate 30% non-price criteria (sustainability/resilience), favoring EU-made components over cheaper Chinese imports.

- CBAM Definitive Phase: Importers must now pay for embedded carbon in steel and aluminum, raising the landed cost of wind towers and solar frames.

- China’s Rebate Cut: Beijing’s removal of the 9% VAT export rebate (April 2026) has further closed the price gap between Chinese and EU hardware.

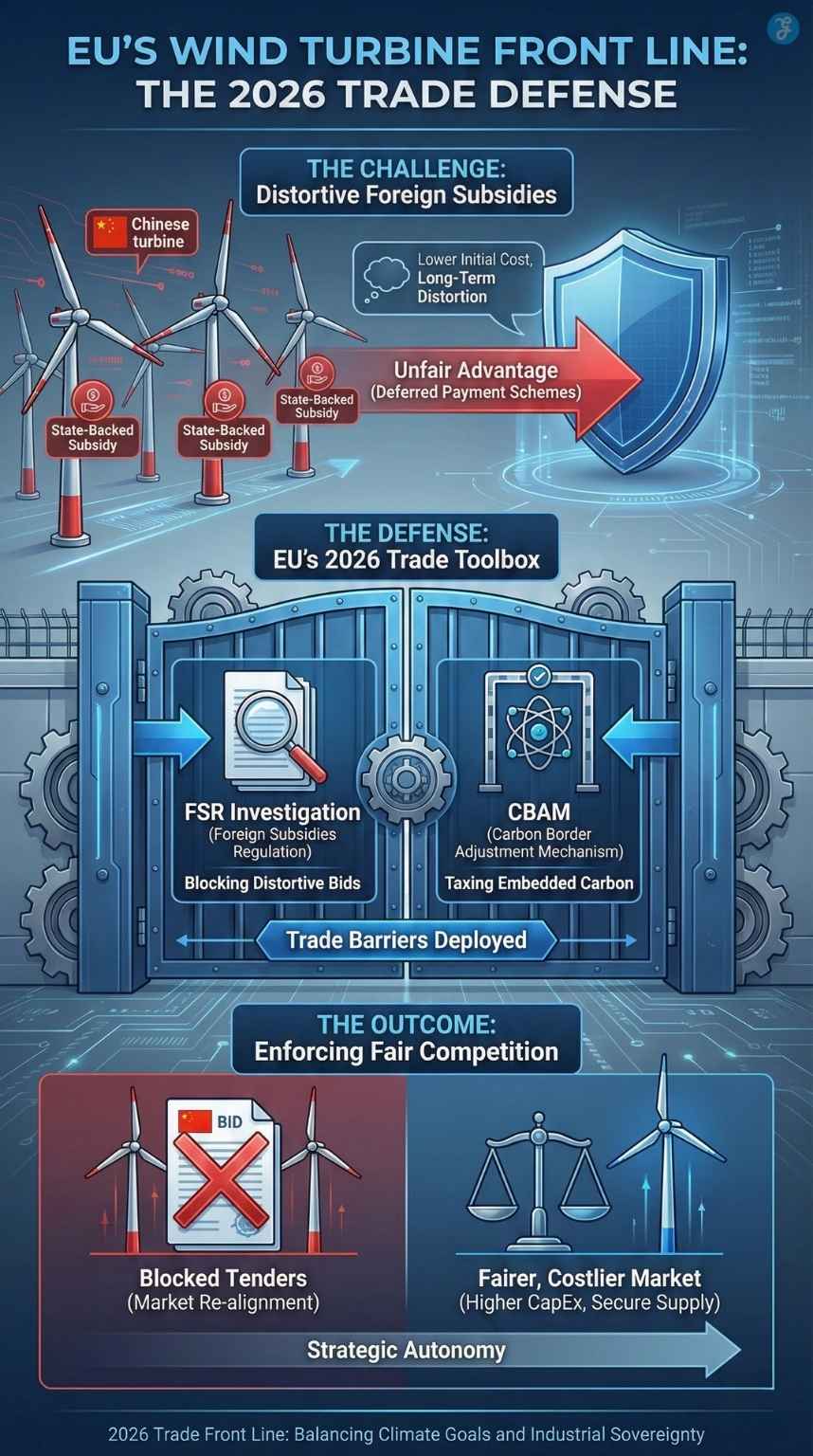

- FSR Investigations: The EU is actively blocking Chinese wind turbine bids found to be backed by distortive state-led financing.

- Traceability Mandates: Strict Forced Labor Regulations require batch-level tracking, shifting supply chains toward “safe harbor” nations like India.

- The Price Floor: 2026 marks the end of declining renewable costs, as the EU prioritizes industrial sovereignty over pure price efficiency.

The Genesis of the 2026 Trade Schism

To understand why EU-China Renewable Energy Trade Barriers 2026 have become so formidable, one must look at the industrial erosion of the early 2020s. By 2024, China controlled over 80% of the global solar supply chain and was rapidly expanding its share in the wind energy sector through aggressive financing and state-backed subsidies.

European manufacturers, such as Meyer Burger and various wind turbine OEMs, found themselves unable to compete with Chinese prices that were often 30% to 50% lower. The EU’s response was not a single “silver bullet” tariff, but rather a “lattice” of regulations designed to favor local content, sustainability, and transparency.

The “Green Paradox”

The central tension of 2026 is the “Green Paradox”: The EU needs the cheapest possible components to meet its 2030 decarbonization targets of 600 GW of solar, yet it cannot afford to trade its Russian gas dependency for a total Chinese technology dependency.

Pillar 1: The Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) Implementation

Starting in January 2026, the Net-Zero Industry Act has moved into its most aggressive phase: mandatory implementation in public procurement.

Mandatory Non-Price Criteria

Unlike previous years, where the lowest price almost always won the contract, 2026 regulations mandate that at least 30% of the auctioned volume (or 6 GW annually) in each member state must be awarded based on “non-price criteria.”

- Sustainability and Resilience: Bidders are now scored on the environmental footprint of their manufacturing. Because many Chinese factories still rely on coal-heavy grids, they struggle to meet the strict carbon-intensity thresholds now required by EU member states like Germany and France.

- Diversification Requirements: If more than 50% of a specific component (like solar wafers or wind nacelles) comes from a single non-EU country, specifically China, the bid is penalized.

- Cybersecurity and Data Sovereignty: In the wind sector, the software and sensors within turbines are now scrutinized as “critical infrastructure.”

The 2026 “Made in Europe” Bonuses

Several nations have introduced “Resilience Bonuses.” For instance, a developer in Italy using EU-manufactured solar cells can now receive a feed-in-premium or a tax credit that offsets the higher cost of the local hardware. This has effectively created a two-tier market: a “Cheap Tier” for private, non-subsidized projects and a “Sovereignty Tier” for public and utility-scale tenders.

Pillar 2: The CBAM “Definitive Phase”

January 1, 2026, was a “Red Letter Day” for trade as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entered its definitive phase. No longer just a reporting requirement, importers must now pay for the carbon embedded in the products they bring into the EU.

Impact on Wind and Solar Materials

While CBAM doesn’t apply to “finished” solar panels yet, it applies to the precursor materials that make up the lion’s share of their cost:

- Steel and Aluminum: Essential for wind turbine towers and solar mounting structures.

- Hydrogen and Cement: Used in the foundation and production processes.

For Chinese manufacturers, who produce steel with significantly higher carbon intensity than their European counterparts, CBAM acts as a de facto tariff. Analysts estimate that CBAM alone has added a 5% to 8% cost premium to Chinese wind towers in the first quarter of 2026.

The Steel Subsidy Trap: Targeting the Wind Backbone

While much of the media focus is on solar panels, the most immediate financial victim of the 2026 trade barriers is the onshore and offshore wind sector. Steel products account for over 70% of the trade volume currently covered by CBAM.

Because Chinese steel production still relies heavily on carbon-intensive blast furnaces, the “Carbon Gap” between Chinese and European steel has become a massive financial liability. Importers of Chinese wind towers are now facing a 15% to 20% increase in total landed costs.

This creates a strategic bottleneck: European wind OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) are struggling to scale production fast enough to replace these penalized imports, leading to a projected 12-month delay in several major Baltic and North Sea offshore projects.

The “Beijing Rebuff”: China’s Export Tax Rebate Removal

Perhaps the most unexpected development in the EU-China Renewable Energy Trade Barriers 2026 narrative didn’t come from Brussels, but from Beijing. On April 1, 2026, China’s Ministry of Finance officially removed the 9% VAT export tax rebate for solar PV products.

Why China Cut Its Own Exports

This move signals a shift in Chinese industrial policy. For years, the rebate allowed Chinese firms to “dump” overcapacity onto global markets at wafer-thin margins. By removing the rebate, Beijing is:

- Forcing Consolidation: Pushing out smaller, inefficient players to stabilize domestic prices.

- Cooling Trade Tensions: Acknowledging that the era of hyper-cheap exports was fueling a global trade war.

- Protecting Margins: Ensuring that the remaining giants like LONGi and JinkoSolar can maintain profitability as they pivot toward higher-value tech like N-type and Perovskite cells.

The “Counter-Strike”: Beijing’s Response and WTO Tensions

As of January 4, 2026, the diplomatic tone between Brussels and Beijing has shifted from cautious negotiation to overt legal confrontation. China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) officially labeled the EU’s trade barriers, specifically CBAM, as “unfair and discriminatory” in a landmark statement.

Beijing’s core argument centers on the EU’s use of “notably high” default carbon intensity values for Chinese products, which MOFCOM claims disregards China’s massive investments in greening its own grid. By applying these default penalties, the EU effectively increases the cost of Chinese steel and aluminum by up to €144 per ton, a rate significantly higher than that applied to competitors like Brazil or Turkey.

This has triggered a dual-track response from China:

- WTO Litigation: China has initiated a formal dispute at the World Trade Organization, arguing that CBAM violates “Most-Favored-Nation” treatment.

- Reciprocal Barriers: Markets are bracing for “tit-for-tat” measures, with Beijing hinting at export restrictions on high-purity quartz and rare-earth magnets, two materials where China holds a near-monopoly and which are vital for the EU’s internal wind and solar manufacturing.

Sector Focus: The Wind Turbine “Front Line”

While solar has faced “soft” barriers, the wind sector is seeing “hard” enforcement through the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR).

The 2026 FSR Investigations

The European Commission is currently conducting deep-dive investigations into Chinese wind turbine OEMs involved in projects across Spain, Romania, and Greece. The focus is on “distortive” financing. Many Chinese firms offered 20-year “buy-now-pay-later” schemes or state-backed guarantees that European banks simply cannot match.

In 2026, the EU began “calling in” these contracts. If a subsidy is found to be distortive, the EU can force the company to divest assets or, more commonly, block them from future tenders. This has led to a significant “chilling effect,” where European project developers are now hesitant to sign contracts with Chinese wind firms for fear of retroactive penalties.

Supply Chain Transparency and Ethics

The EU Forced Labor Regulation, fully operational in 2026, has added another layer of complexity.

The Xinjiang Traceability Mandate

Because a significant portion of global polysilicon originates in Xinjiang, the burden of proof has shifted to the importer. In 2026, “blind spots” in the supply chain are no longer legally acceptable.

- Batch-Level Traceability: Modules must be traced back to the specific batch of silicon used.

- The Shift to “Safe Harbors”: This has triggered a massive investment boom in Indian and Southeast Asian manufacturing hubs, as Chinese firms scramble to set up “clean” supply chains outside of China to bypass EU and US restrictions.

Economic Analysis: The Price of Sovereignty

What does this mean for the “bottom line” of the energy transition? The EU-China Renewable Energy Trade Barriers 2026 have effectively ended the decade-long trend of falling solar and wind costs.

| Metric | Pre-2026 Average | 2026 Forecast | Change |

| Solar Module Price ($/W) | $0.11 | $0.14 | +27% |

| Wind Turbine CapEx | €1.1M/MW | €1.3M/MW | +18% |

| Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | Declining | Stabilizing/Rising | Trend reversal |

Impact on Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)

Corporate energy buyers are feeling the squeeze. In Q1 2026, PPA prices in Europe have risen for the first time in years as developers pass on the costs of CBAM, NZIA compliance, and higher hardware prices.

Internal Barriers: Grid Congestion and the Logistics of Decoupling

A critical “internal” barrier emerging in 2026 is the growing disparity between renewable generation and transmission capacity. Even if the EU successfully blocks Chinese components and replaces them with local ones, the “Green Paradox” is worsened by a failing grid.

As the EU implements these trade barriers, the cost of project financing is rising due to grid connection delays, which in some regions like Poland and Italy now exceed five years. Developers are warning that protectionism is “fixing the supply chain but ignoring the pipes.” Without a massive, synchronized investment in cross-border interconnections (RESourceEU), the higher costs of “Sovereign Energy” may lead to a market cooling in late 2026, as investors seek higher returns in less regulated markets like Southeast Asia or North Africa.

Strategic Outlook: 2026 and Beyond

The trade barriers of 2026 are not merely protectionist; they are a blueprint for a new “Green Industrial Policy.”

The Rise of “Friend-Shoring”

We are seeing a realignment where the EU is increasingly looking toward the United States (via the Inflation Reduction Act synergies) and India to build a “democratic supply chain.” While China will remain a dominant force due to its sheer scale, its role as the “uncontested supplier” of the European Green Deal is over.

Potential for Retaliation

The risk of a broader trade war remains high. Beijing has already hinted at potential restrictions on rare earth magnets, essential for the direct-drive permanent magnets used in many European wind turbines. If China weaponizes its control over these raw materials, the EU’s 2026 barriers may need to be re-evaluated for the sake of energy security.

Final Thought: Navigating Europe’s Green Fortress

The EU-China Renewable Energy Trade Barriers 2026 represent the painful but perhaps necessary “growing pains” of a mature energy market. By prioritizing industrial resilience and carbon accounting over pure price efficiency, the EU is attempting to build a transition that is both green and strategically autonomous.

For analysts and developers, 2026 is no longer about finding the cheapest panel; it is about navigating a complex geopolitical map where every component carries a “sovereignty score.” The success of the European Green Deal now rests on whether the EU can scale its internal manufacturing fast enough to fill the gap left by the “Barriers of 2026.”