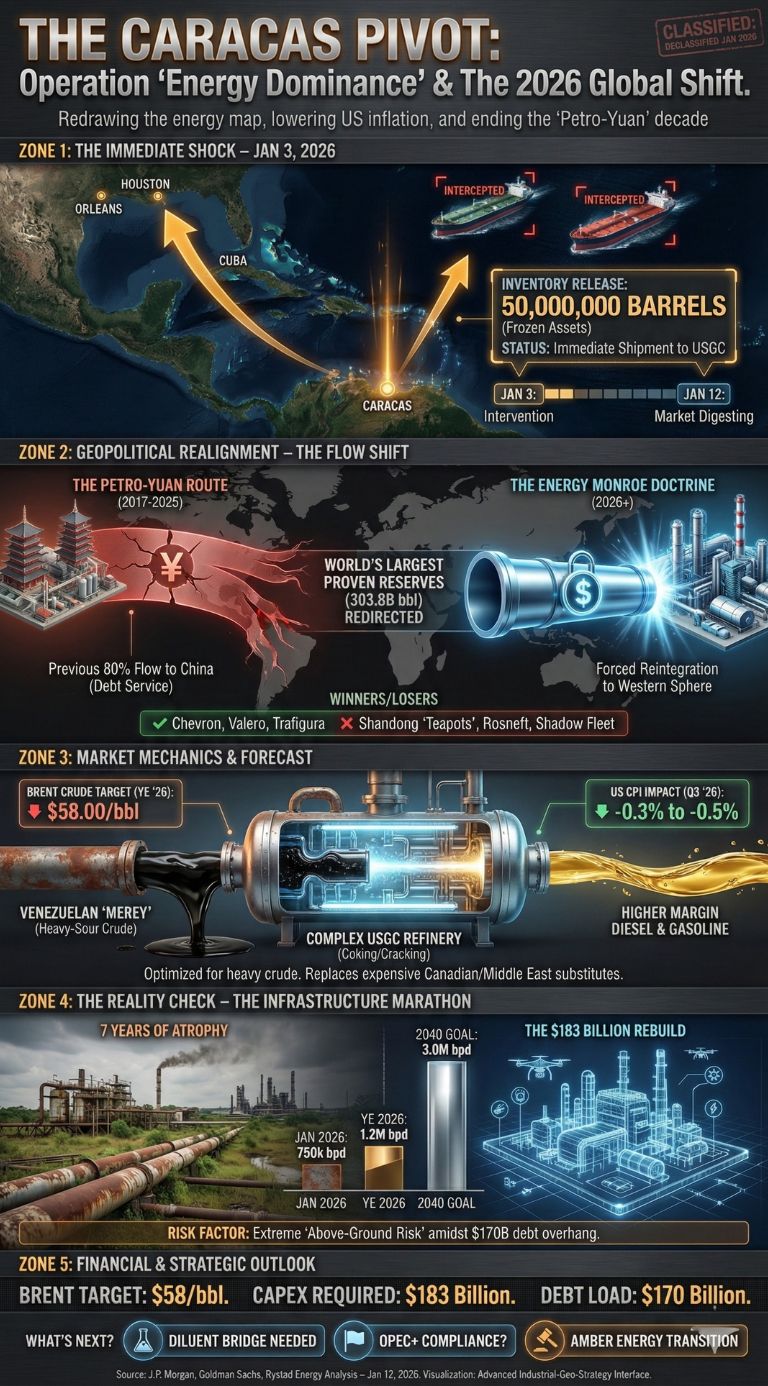

The dramatic military intervention in Caracas on January 3, 2026, culminating in the removal of Nicolás Maduro, has triggered a seismic shift in global energy. The immediate turnover of 50 million barrels of sanctioned oil to the United States and the subsequent resumption of exports marks a strategic pivot that promises to lower U.S. inflation, redefine the Brent-WTI spread, and effectively end China’s decade-long energy dominance in Latin America.

Key Takeaways

-

Immediate Inventory Surge: The release of 30–50 million barrels of “frozen” inventory acts as a massive short-term supply shock to the U.S. Gulf Coast.

-

Brent Crude Pricing: Market analysts at J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs predict a bearish medium-term outlook, with Brent potentially settling at $58/bbl by year-end 2026.

-

Inflationary Cooling: Lower energy input costs for U.S. refineries are projected to shave 0.3%–0.5% off the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) by Q3 2026.

-

Capital Requirements: Restoring production to 3 million bpd is a “marathon, not a sprint,” requiring upwards of $183 billion in capital expenditure over the next 15 years.

-

Geopolitical Realignment: The “Energy Monroe Doctrine” effectively forces a pivot away from the “petro-yuan,” targeting China’s 600,000 bpd supply of discounted Venezuelan crude.

The January 2026 intervention was the inevitable conclusion of a decade of industrial atrophy and geopolitical friction. For years, Venezuela’s state-owned oil giant, PDVSA, served as a “piggy bank” for the ruling elite, leading to a catastrophic decline in production from 3.2 million barrels per day (bpd) in the late 1990s to a precarious 750,000–950,000 bpd by 2025.

The capture of Maduro on January 3, 2026, by U.S.-backed forces, followed by the immediate seizure of two Russia-flagged tankers in the Atlantic, signaled a new era of “Energy Dominance.” This was not merely a change in government; it was a forced reintegration of the world’s largest proven oil reserves into the Western economic sphere. As of January 12, 2026, the global market is still digesting the implications of a “re-globalized” Venezuelan energy sector that had been largely dark for seven years.

Market Dynamics: The Return of the Heavy-Sour Barrel

The immediate impact of Venezuela oil exports to USA is felt most acutely in the “spread” between light and heavy crudes. U.S. Gulf Coast (USGC) refineries are complex machines optimized for the heavy, high-sulfur (sour) crude that Venezuela produces in the Orinoco Belt. For years, these refiners paid a premium for Canadian or Middle Eastern substitutes. The sudden influx of Venezuelan “Merey” grade crude allows these refiners to capture higher margins, eventually translating to lower pump prices for diesel and gasoline.

| Market Indicator | Pre-Intervention (Dec 2025) | Current Status (Jan 2026) | 2026 Year-End Forecast |

| Brent Crude Price | $65.40 / bbl | $61.17 / bbl | $58.00 / bbl |

| WTI Crude Price | $60.10 / bbl | $57.01 / bbl | $54.50 / bbl |

| Venezuelan Production | 870,000 bpd | 795,000 bpd (Restricted) | 1,200,000 bpd |

| Global Surplus | 1.8 Million bpd | 2.2 Million bpd | 2.5 Million bpd |

Financial analysts suggest that while the initial risk premium caused a 2% “dead cat bounce” in prices on January 8, the underlying fundamentals are decisively bearish. With a global surplus already exceeding 2 million bpd, the resumption of Venezuelan exports adds “fuel to the fire” of an oversupplied market.

Infrastructure & The Financial Barrier to Restoration

While the geopolitical “win” is clear, the technical reality on the ground is sobering. Decades of “deferred maintenance” in the Orinoco Belt have resulted in severely reduced operational efficiency. Most pipelines are corroded, and “upgraders”—the massive plants that turn tar-like extra-heavy crude into exportable oil—are operating at less than 30% capacity.

| Investment Phase | Estimated Cost (USD) | Projected Output Increase | Timeline |

| Emergency Repair | $15–$25 Billion | +250,000 bpd | 2026–2027 |

| Mid-Cycle Restoration | $41–$50 Billion | +500,000 bpd | 2028–2030 |

| Full Industrial Rebuild | $183–$200 Billion | +2,000,000 bpd | 2026–2040 |

| Gas Sector Monetization | $5–$8 Billion | 1.5 Bcf/day (Export) | 2027–2032 |

President Trump’s administration has indicated that U.S. majors like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and ConocoPhillips will be expected to “foot the bill” for these repairs in exchange for favorable 30-year concessions. However, the $183 billion price tag represents a significant capital commitment, especially in a low-price environment where Brent is hovering near $60.

Corporate Winners and the Trade Route Reshuffle

The resumption of exports creates a “musical chairs” scenario in the global shipping and refining sectors. The primary “losers” are the Chinese “teapot” refineries in the Shandong province, which had become reliant on discounted, sanctioned Venezuelan crude. With the U.S. now dictating oil flows, these refiners will likely be forced to bid for more expensive Middle Eastern grades or Russian Urals, increasing their operational costs.

| Sector | Primary Winners | Primary Losers |

| Refining | Valero, Marathon Petroleum, PBF Energy | Chinese Independent “Teapots” |

| Upstream | Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Amber Energy (Citgo) | Rosneft (Russia), CNPC (China) |

| Logistics | Maersk Tankers, Trafigura, Vitol | Sanctioned “Shadow Fleet” Operators |

| National Interests | United States (Energy Security) | Cuba (Loss of Subsidized Crude) |

Chevron holds a unique advantage as the only U.S. major that maintained a presence through the crisis. Their “Petropiar” upgrader is one of the few functional facilities in the country, positioned to lead the first wave of ramped-up production.

Geopolitical Realignment: Ending the “Petro-Yuan” Influence

Since 2017, Venezuela has been a cornerstone of China’s strategy to bypass the U.S. dollar in energy trades. By 2025, nearly 80% of Venezuelan crude was flowing to China, often to service over $60 billion in sovereign debt. The 2026 intervention effectively “nationalizes” these assets in favor of Western creditors.

The U.S. Treasury (OFAC) is expected to issue new “General Licenses” that prioritize debt repayment to U.S. bondholders and corporate claimants (such as those involved in the Citgo/Amber Energy transition) over Chinese and Russian loans. This “financial quarantine” of Eastern interests is a core pillar of the new administration’s Latin American policy.

Data & Key Statistics: The 2026 Energy Baseline

-

Total Proven Reserves: 303.8 Billion Barrels (World’s Largest).

-

Current Production Floor: 750,000 bpd (January 2026 low).

-

Targeted Production (End of 2026): 1.1–1.2 Million bpd.

-

U.S. Export Target: 500,000 bpd by Q4 2026.

-

Estimated U.S. CPI Impact: -0.4% (Direct and indirect energy cost reduction).

-

Sovereign Debt Burden: $170 Billion (including $100 Billion in unpaid interest).

Expert Perspectives: Optimism vs. Realism

“We are looking at the most significant upside risk to global supply for the 2026–2027 period,” notes Natasha Kaneva of J.P. Morgan. “If the U.S. can stabilize the political environment and restore diluent flows—the light naphtha needed to blend with heavy crude—we could see an immediate 250,000 bpd rebound.”

Conversely, Rystad Energy analysts warn that the “above-ground risks” remain extreme. “Venezuela has nationalized its oil industry twice before. Convincing boards at Exxon or Shell to commit $10 billion to a country with a $170 billion debt overhang and a history of expropriation will require ironclad legal guarantees that don’t yet exist.”

What Happens Next?

The market is currently watching three critical “Next Steps”:

-

The “Diluent” Bridge: Venezuela cannot export its heavy crude without mixing it with lighter liquids. Watch for a massive increase in U.S. light naphtha exports to Caracas in February 2026.

-

OPEC+ Compliance: If Venezuela adds 400,000 bpd to the market by December, OPEC+ (led by Saudi Arabia) may be forced to deepen their own cuts to prevent a price collapse toward $50/bbl.

-

The “Amber Energy” Factor: The transition of Citgo to its new owners, Amber Energy, will be the blueprint for how Venezuelan assets are managed and how revenue is funneled into “blocked accounts” to prevent it from reaching remnants of the old regime.

Final Thoughts

The resumption of Venezuela oil exports to USA is a masterclass in using energy policy as a geopolitical weapon. While it offers a “quick fix” for U.S. inflation and refiner margins, the long-term success depends on a multi-decade, multibillion-dollar reconstruction effort. For the first time in a generation, the “oil map” of the Americas is being redrawn, with Washington firmly holding the pen.