We often hear that automation is taking over. Machines assemble products, sort packages, drive vehicles, and analyze massive datasets without rest. In factories, hospitals, and even households, intelligent systems now perform tasks that were once considered uniquely human. The narrative is familiar: faster, cheaper, smarter — all thanks to machines.

But there’s another side to this story.

Despite the sophistication of automation technologies, the systems behind them don’t build or maintain themselves. They rely on human engineers — people with the knowledge to model complex behavior, write stable control algorithms, solve high-order equations, and turn abstract physical principles into practical systems that actually work. In the world of robotics, that need is even more visible.

When Motion Gets Complicated

Think of a bipedal robot — a two-legged machine built to walk upright, shift weight, respond to its environment, and maintain balance under shifting loads. From a distance, the motion might seem simple. But achieving that movement requires detailed modeling, precise simulation, and real-time control.

These systems don’t just “walk” on command. Engineers must solve the equations of motion — often using the Newton-Euler method or addressing the Cauchy problem — to predict how the robot’s structure responds to forces at every joint. In systems with five or seven degrees of freedom (DOF), those calculations quickly become complex, and each mistake introduces the risk of instability or failure.

Impulse control, force feedback, and multi-axis drive coordination must work together seamlessly. That doesn’t happen with plug-and-play solutions. It happens when engineers understand the real mechanics and can integrate physical models with real-world constraints.

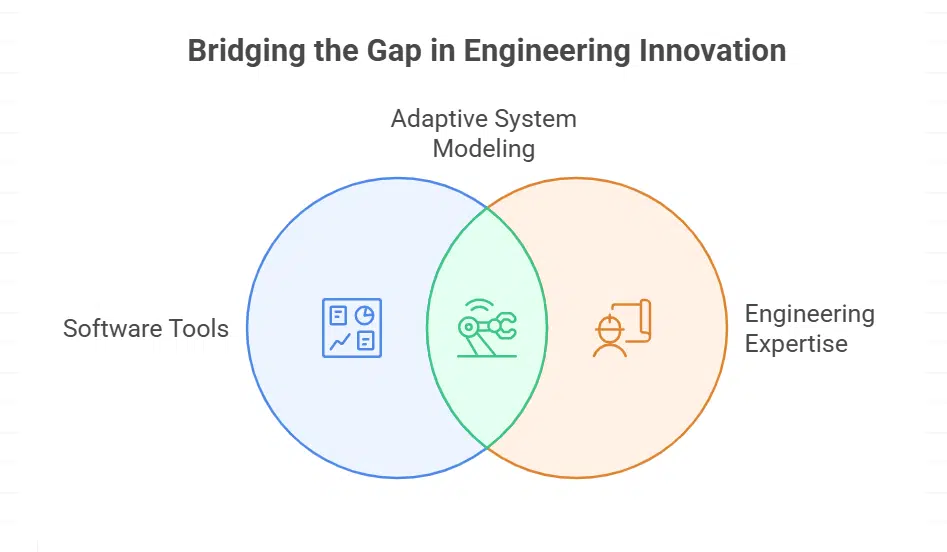

This is exactly the kind of problem-solving offered by robotics engineering teams working at the intersection of simulation, design, and testing. They bridge the gap between theoretical capability and actual function — turning concepts into systems that operate reliably under pressure.

Why Tools Alone Aren’t Enough

Software tools today are powerful. Many platforms offer motion simulation, CAD integration, or even basic AI-driven control suggestions. But tools don’t make decisions. They don’t account for gaps in modeling, edge-case behaviors, or unexpected interactions between subsystems. That’s where engineers step in.

Too often, teams lose time and budget wrestling with fragmented toolchains, limited integration between testing environments, or hard-to-debug control behavior. Off-the-shelf libraries can’t resolve these challenges. Even experienced developers sometimes struggle to adapt complex mathematical models to real applications — especially when systems require precise control over force dynamics or non-linear feedback.

It’s not just about writing code. It’s about knowing what the code must reflect — the friction in a joint, the delay in a response loop, the behavior of a load under acceleration. That level of modeling requires deep understanding and creative adaptation. It also requires engineers who can look past the UI and into the equations driving the entire system.

Supporting Innovation Behind the Scenes

Companies developing robotics systems often rely on outside engineering support to get past critical roadblocks. Whether it’s simulating a 7-DOF anthropomorphic arm or integrating a new control method into a test bench setup, expert engineering services make the difference between experimental and operational.

These teams work on challenges like:

- dynamic motion simulation under real-world constraints,

- drive control with feedback-based impulse correction,

- solving coupled differential equations across multi-joint systems,

- translating physical models into code that matches testbench behavior.

The value here isn’t just in solving one issue. It’s in enabling progress — making systems testable, predictable, and scalable. That’s what moves robotics forward: a combination of powerful tools and experienced people who know how to use them.

The Human Factor Endures

For all the advances in automation, robotics still needs engineers. Not just to design — but to debug, adapt, simulate, test, and improve. When a robot walks across a lab floor, or responds smoothly to unexpected force input, that’s not just automation. That’s the result of human intelligence baked into every control loop, every calculated motion, every model running under the surface.

It’s the engineer who anticipates failure modes, rechecks the data, and ensures the system works not just once, but every time — across varied conditions and unexpected changes. That kind of reliability doesn’t emerge from automation alone. It’s designed, tested, and safeguarded by people who know what’s at stake.

Automation reduces effort. Human skill gives it shape.

And as long as machines move, adapt, and learn in physical space, there will be a place for engineers — people who understand not just what machines do, but how and why they do it.