In the vast expanse of our galaxy, about 880 light-years from Earth, lies a truly astonishing world known as Tylos — officially designated as WASP-121b. This gas giant, orbiting a yellow-white star named Dilmun, has become one of the most studied exoplanets in our cosmic neighborhood. But what makes this world so extraordinary isn’t just its size or orbit — it’s the exotic, extreme environment sculpted by its proximity to its parent star and the materials from which it formed.

Tylos is roughly 1.75 times the radius of Jupiter, yet only about 1.16 times as massive. Despite being a gas giant, this planet exists in a constant state of physical duress. Its dayside temperature exceeds 3,000°C (5,432°F) — hot enough to vaporize metals and rocks, while the nightside remains a sizzling 1,500°C (2,732°F). Such extremes place Tylos in the category of ultra-hot Jupiters — gas giants that orbit extremely close to their stars.

A Close Orbit That’s Literally Shredding the Planet

Tylos completes one full orbit around its host star every 30 Earth hours. That’s barely over a day — a blink of time in cosmic terms. It is so close to Dilmun, which is 1.5 times larger and hotter than our Sun, that its atmosphere is being stripped away. The planet’s gaseous envelope is puffed up and unstable, with its outer layers already evaporating into space due to the intense stellar radiation.

This close orbit not only dooms the planet to a shortened existence but also makes it an ideal subject for astronomical research. As Tylos frequently transits between its star and Earth, scientists can examine the light that filters through its atmosphere during these transits. This technique, known as transmission spectroscopy, enables them to detect various molecules and trace the planet’s atmospheric composition.

JWST Sheds Light on an Atmosphere of Vaporized Rock and More

Using the cutting-edge capabilities of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers recently made a remarkable discovery: the presence of silicon monoxide (SiO) in Tylos’s atmosphere — a clear indicator of vaporized rock. This molecule is extremely rare and difficult to detect, but its identification offers powerful evidence that this planet is being scorched so intensely that even solid minerals are turning into gas.

Alongside silicon monoxide, the researchers also detected water vapor (H₂O), carbon monoxide (CO), and methane (CH₄). These molecular fingerprints tell a story not just of the planet’s current state, but of how it originally formed billions of years ago.

According to lead researcher Dr. Thomas Evans-Soma of the University of Newcastle in Australia, the relative abundances of carbon, oxygen, and silicon provide critical clues into the origins of Tylos. The ratios suggest that this exoplanet was built from rocky pebbles and dust—the byproducts of a young star’s formation.

From Pebbles to Planets: How Tylos Was Born

To understand Tylos’s creation, it helps to consider how solar systems form. Stars like Dilmun are born inside dense molecular clouds. As they grow, they pull in surrounding material, which flattens into a spinning protoplanetary disk. Over time, leftover gas and dust in the disk collide and stick together, forming tiny pebbles and eventually planetesimals—the building blocks of planets.

The composition of Tylos’s atmosphere suggests it was assembled from this leftover material — especially dust and rock particles that were rich in silicon and other minerals. But perhaps more importantly, the ratios of methane to water offer hints about where in the disk Tylos originally formed.

The Icy Line: A Cosmic Marker in Planet Formation

In planetary science, there’s something called the ice line or snow line — a point in a protoplanetary disk beyond which certain ices can condense. Inside this line, it’s too hot, so water, methane, and other volatiles exist as gas. Outside the line, they can freeze into ice and contribute to planet-building.

For our Solar System, this line lies between Jupiter and Uranus. But Dilmun is hotter than our Sun, so the snow line in that system would lie even farther out. Based on the molecule ratios in Tylos’s atmosphere, researchers concluded that the planet must have formed beyond the methane snow line, where methane was gaseous and water remained frozen.

This confirms the prevailing theory that hot Jupiters like Tylos couldn’t have formed in their current orbits. The intense radiation would have prevented gas from clumping and forming a planet. Instead, Tylos likely formed farther out and then migrated inward through gravitational interactions with other planets or remnants of the disk.

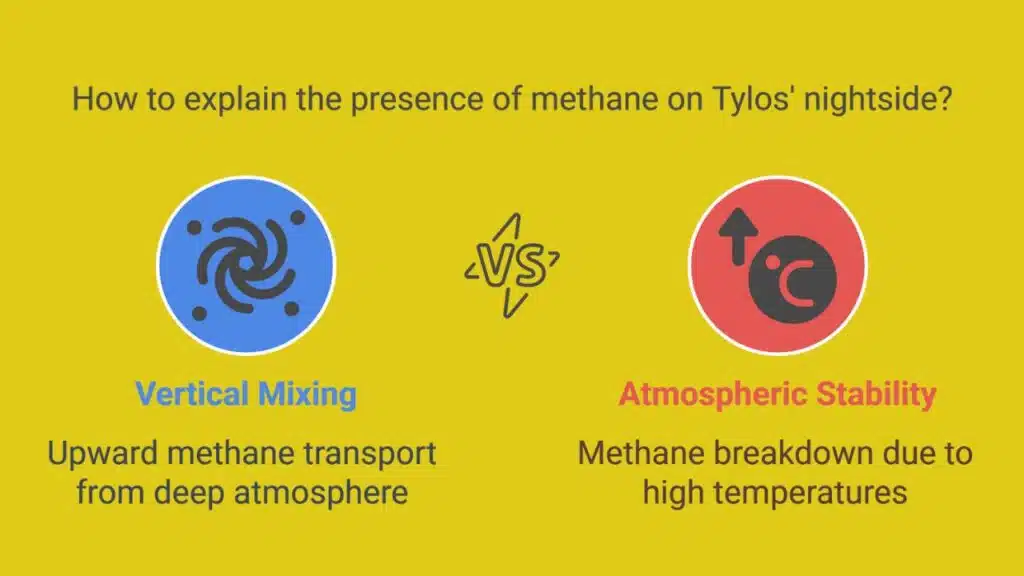

Methane on the Nightside: A New Atmospheric Mystery

Another twist in the Tylos story emerged when scientists noticed abundant methane on the nightside of the planet — the side that never faces the star due to tidal locking. Methane is typically unstable at high temperatures and should not survive in the upper layers of the atmosphere. However, JWST clearly detected it at altitudes where it wasn’t expected.

The most likely explanation is a phenomenon known as vertical mixing. Powerful updrafts deep inside the atmosphere may be pushing methane-rich air upward to cooler layers, allowing it to be detected before it breaks down. This kind of extreme vertical circulation is rare in known planetary atmospheres and suggests that Tylos is not just hot, but also highly dynamic.

This challenges exoplanet dynamical models, which will likely need to be adapted to reproduce the strong vertical mixing we’ve uncovered on the nightside,” said Dr. Evans-Soma. These atmospheric processes open new frontiers for our understanding of how heat, chemistry, and motion interact on alien worlds.

A 3D View: Layers of Exotic Weather and Escaping Hydrogen

Earlier studies from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have also painted a 3D picture of Tylos’s atmosphere, revealing multiple layers each with distinct characteristics:

- Lower Layer: Filled with gaseous iron and magnesium, created by extreme temperatures that turn metals into vapor.

- Middle Layer: Dominated by sodium gas and strong wind jets that can circle the entire planet at thousands of kilometers per hour.

- Upper Layer: Consisting primarily of hydrogen, which is so hot that it’s escaping into space, creating a kind of comet-like tail behind the planet.

These observations emphasize just how complex and violent the atmosphere of WASP-121b really is. Unlike anything found in our Solar System, it represents a new class of planetary phenomena.

Why Tylos Matters for Exoplanetary Science

Despite being just one of nearly 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, Tylos has offered more detailed insight than almost any other alien world. It serves as a natural laboratory for understanding how massive planets evolve, migrate, and respond to intense stellar radiation.

By analyzing its chemical fingerprints, orbital behavior, and dynamic weather, astronomers can better model how hot Jupiters form and behave, and how similar gas giants might evolve across different star systems. Tylos not only validates some planetary formation models but also challenges others, particularly around atmospheric dynamics and vertical mixing.

More importantly, the research highlights the power of next-generation observatories like JWST, which allow us to probe distant planets in unprecedented detail — right down to the molecular ingredients of their skies.

A Melting World That Still Has Secrets to Share

Even after years of study, Tylos (WASP-121b) continues to surprise and intrigue astronomers. From vaporized rock clouds and escaping hydrogen to unexpected methane patterns, it embodies the complexity and wonder of our galaxy’s planetary diversity.

With continued observations from JWST and future telescopes, scientists hope to unlock even more secrets of this melting world. Tylos may be one of the most extreme exoplanets we know, but it’s also one of the most informative — teaching us not only about its own bizarre nature but also about the processes that shape worlds across the universe.

The Information is Collected from Science Alert and Yahoo.