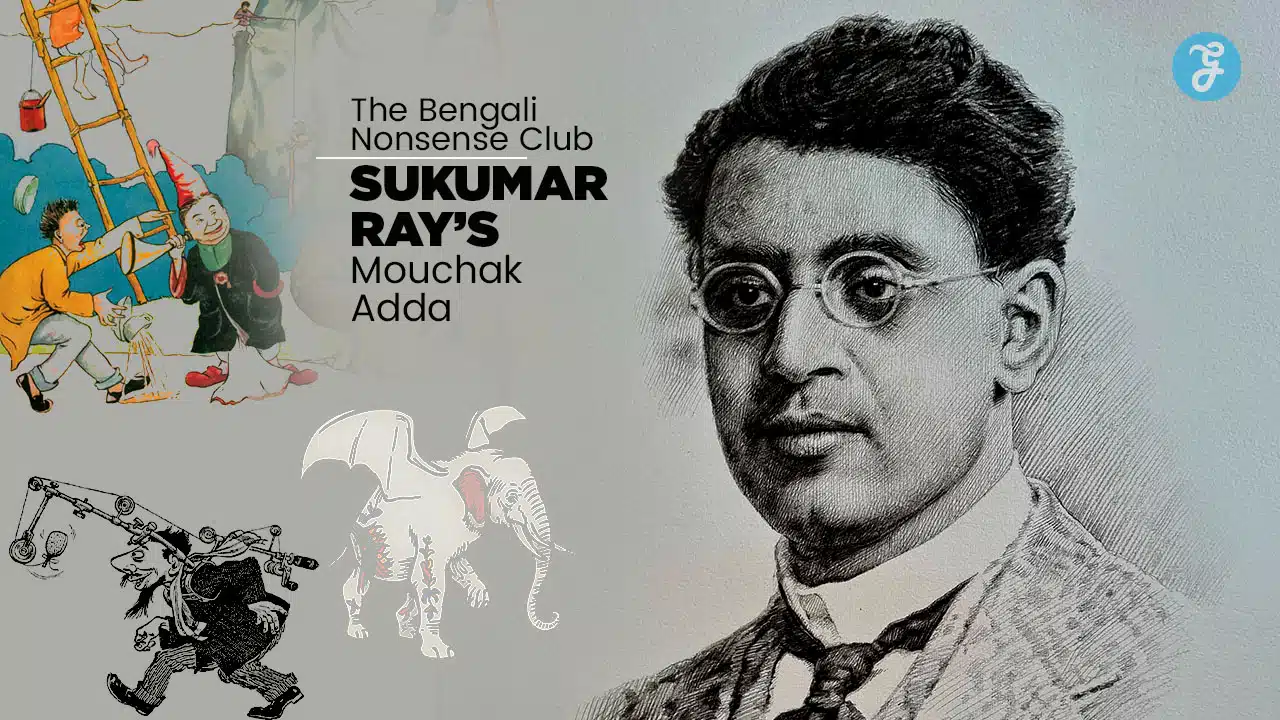

Before social media memes, parody accounts, or stand-up comedy shows, Bengal had its very own hub of laughter and absurd brilliance. This was Mouchak Adda, also known as the Monday Club, a gathering created by the legendary writer and humorist Sukumar Ray. Best remembered for his masterpiece Abol Tabol, Ray used the adda as a buzzing hive of creativity where satire, doodles, rhymes, and laughter were shared freely.

The word “Mouchak” means “beehive”—and the club lived up to its name. Just like bees buzzing together to create honey, members of this adda brought their wit and imagination together to create a new genre in Bengali literature: literary nonsense.

Calcutta in the Age of Wit

The early 20th century was a remarkable period for Calcutta. The Bengal Renaissance had sparked innovation in literature, art, and science. The city was alive with political debates, new publications, and artistic revolutions. Humor became not just entertainment but a way of questioning colonial authority.

The Ray Family Influence

Sukumar Ray was born into a household where art and science coexisted. His father, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, was a writer, musician, painter, and printing pioneer who started Sandesh magazine. Sukumar continued this legacy, mixing his scientific training in London (in photography and printing technology) with his natural talent for wordplay and satire.

Birth of the Mouchak Adda

The club was affectionately called Mouchak or Mouchak Sabha, symbolizing a hive of buzzing ideas. It wasn’t just a casual tea-time adda — it was a structured yet playful space where rules were mocked, and “serious nonsense” was celebrated.

The Monday Gatherings

Every Monday, Sukumar Ray and his circle of friends gathered to exchange:

-

Nonsense poems (precursors to Abol Tabol)

-

Satirical skits poking fun at colonial officials

-

Mock minutes of meetings, written in bureaucratic language but filled with absurdity

-

Doodles and caricatures, passed around like creative challenges

These sessions were filled with infectious laughter and childlike imagination, but they also carried deeper messages hidden in the humor.

The Members and Their Madness

The adda wasn’t just Sukumar Ray alone. Writers, musicians, artists, and thinkers joined the gatherings. Many were contributors to Sandesh and belonged to Calcutta’s intellectual circles.

Roles Inside the Club

Every member was encouraged to contribute—whether through rhymes, songs, or sketches. Some created parodies of government officials; others made up absurd characters. Together, they created a world where nonsense had its own logic.

| Activity | How It Looked in Mouchak Adda |

|---|---|

| Meeting minutes | Written in parody of bureaucracy |

| Literary contributions | Rhymes, limericks, nonsense verse |

| Art & sketches | Doodles of bizarre creatures |

| Performances | Mock plays, silly debates, music |

What Happened Inside the Adda?

Colonial officials and their obsession with rules often became targets of parody. For example, minutes of the adda were drafted as if they were government records—except they recorded jokes, absurd laws, and nonsensical decisions.

Birthplace of Characters

Many of the absurd creatures and characters in Abol Tabol—like the Katth Buro, Ramgorurer Chhana, or Huko Mukho Hyangla—can be traced back to experiments and jokes shared in Mouchak.

Fusion of Word and Image

Sukumar’s doodles were passed around, and others added details. This collaborative style gave rise to a playful mix of illustration and text—something that made his later works so unique.

From Adda to Literature

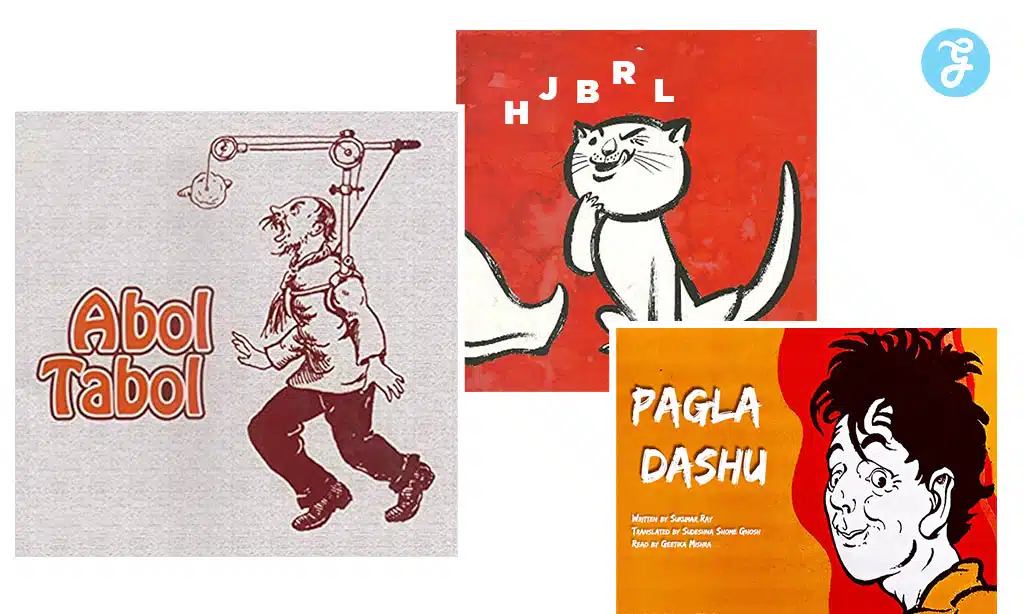

Abol Tabol: The Crown Jewel

Published just days before Sukumar Ray’s untimely death in 1923, Abol Tabol is now considered the Bible of Bengali nonsense literature. But the seeds of these verses were planted in the adda.

Example: The poem about the Katth Buro (a wooden old man) reflects absurdity but also hints at bureaucratic rigidity—exactly the kind of satire that flourished in Mouchak.

HaJaBaRaLa and Pagla Dashu

-

HaJaBaRaLa—a surreal novella blending dream logic with absurd comedy, often compared with European surrealists.

-

Pagla Dashu—stories of a madcap schoolboy who defies authority, clearly echoing the rebellious spirit of Mouchak.

Why Mouchak Still Matters

Mouchak was not just about laughter—it was about finding freedom through nonsense. Humor was a subtle way to resist authority and critique social rigidity.

Inspiration for Generations

The adda’s spirit lived on in Satyajit Ray, Sukumar’s son, who not only revived Sandesh but also brought humor and satire into his own writings and films. Even today, Bengali children grow up reading Abol Tabol, unknowingly inheriting the legacy of Mouchak.

| Mouchak Adda | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Nonsense rhymes | Internet memes, parody accounts |

| Satirical skits | Stand-up comedy shows |

| Doodles | Comic strips, webtoons |

| Collaborative adda | Online forums, group chats |

A Digital Age Beehive

If Mouchak existed today, it might look like a Facebook humor group, a parody Instagram page, or even a collaborative meme lab. The format would change, but the buzzing energy of collective nonsense would remain the same.

Takeaways

The story of Sukumar Ray’s Mouchak Adda shows us that nonsense is not meaningless—it is a form of resistance, creativity, and joy. What began as a small Monday club in colonial Calcutta went on to inspire generations of readers and writers.

Even today, when we laugh at a nonsense verse from Abol Tabol, we are hearing the faint buzz of that beehive where imagination reigned supreme.

Mouchak was not just an adda. It was a movement—a buzzing hive where nonsense became timeless sense.