As of early 2026, the global energy landscape is undergoing a silent but seismic shift as sodium-ion batteries exit the laboratory and enter mass production. This transition represents more than just a new chemical formula; it is a fundamental restructuring of the geopolitical and economic architecture of the 21st century, promising to decouple energy storage from the volatile constraints of the lithium supply chain.

Key Takeaways

- Industrial Scale Achieved: By January 2026, major battery conglomerates including CATL and BYD have successfully operationalized gigawatt-scale sodium-ion facilities, moving the technology from “prototype” to “product.”

- The Decoupling Strategy: Sodium-ion represents a strategic hedge for Western and Asian economies against the “Lithium Triangle” monopoly, utilizing raw materials that are universally abundant and politically neutral.

- The Cold Weather Advantage: Unlike lithium-ion, which falters in freezing temperatures, sodium-ion technology retains over 90% capacity at -20°C, solving a critical adoption hurdle for EVs in northern climates.

- Economic Paradox: While raw material costs are significantly lower, current unit costs for sodium batteries remain higher than mature LFP cells due to a lack of manufacturing scale, a gap expected to close by late 2027.

- A New Duopoly: The market is not heading toward a total replacement of lithium but rather a specialized tiered system: sodium for grid storage and entry-level mobility, and lithium for high-performance applications.

The Trigger: The “Lithium Shock” of Late 2025

While sodium-ion technology has been simmering in R&D labs for a decade, the catalyst for its sudden commercial explosion was the “Lithium Shock” of Q4 2025. Just as analysts were predicting a surplus, a convergence of supply disruptions in the “Lithium Triangle” (Chile, Argentina, Bolivia) and new export controls from major refining nations caused spot prices for lithium carbonate to rally unexpectedly.

This volatility served as the final warning shot for global automakers. The realization that their entire supply chain was pegged to a single, volatile commodity forced an immediate pivot. It transformed sodium-ion from an “experimental science project” into an urgent industrial imperative.

By January 2026, the response was swift. CATL accelerated the rollout of its “Naxtra” brand, while BYD began integrating sodium cells into its high-volume “Seagull” micro-EVs. Simultaneously, the market witnessed a “capital rotation”—investment funds that had previously poured billions into lithium mining began diverting capital toward soda ash refinement and hard carbon anode production, signaling that the smart money sees salt not just as a seasoning, but as the new oil.

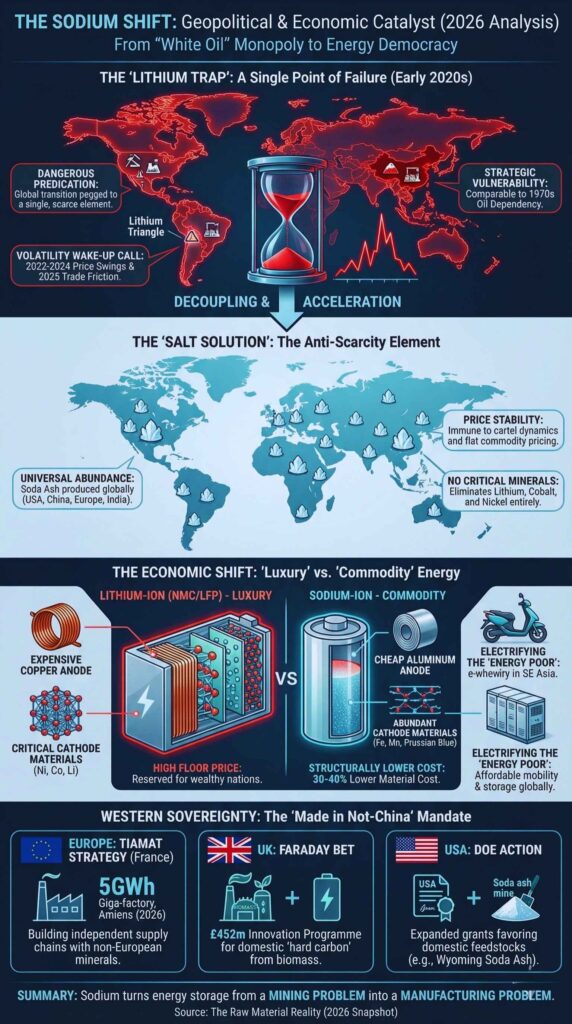

The Geopolitical and Economic Catalyst: Why the Shift is Happening Now?

To understand the sudden ascendancy of sodium-ion technology in 2026, one must look beyond the engineering specifications and into the volatile history of the “Lithium Rush” that characterized the early 2020s. For nearly a decade, the global transition to renewable energy and electric mobility was dangerously predicated on a single, scarce element: lithium. This reliance created a “single point of failure” for the global economy. The price volatility witnessed between 2022 and 2024, where lithium carbonate prices swung violently, served as a wake-up call for automakers and policymakers. It became evident that relying on a mineral concentrated in the geopolitical hotspots of the “Lithium Triangle” (Chile, Argentina, Bolivia) and refined almost exclusively in China was a strategic vulnerability comparable to the oil dependency of the 1970s.

The rise of sodium-ion batteries is the industrial answer to this vulnerability. Sodium is not merely a cheaper alternative; it is the “anti-scarcity” element. Sodium carbonate, or soda ash, is one of the most abundant industrial chemicals on Earth, produced in massive quantities in the United States, China, Europe, and India. It is historically stable in price and immune to the cartel-like market dynamics that plague rare earth metals. The events of late 2025, which saw intensified trade friction and tariff wars over critical minerals, accelerated the push for a battery chemistry that uses no lithium, no cobalt, and no nickel.

Furthermore, the economic implications of this shift are profound for the “energy poor.” In the previous lithium-dominated era, the high floor price of battery cells meant that electrification was a luxury reserved for wealthy nations and premium consumers. Sodium-ion technology breaks this floor. By utilizing aluminum current collectors at the anode—replacing the expensive copper required for lithium-ion—and employing abundant iron and manganese in the cathodes, the material cost of a sodium-ion cell is structurally 30% to 40% lower than its lithium counterpart. This fundamental economic difference is what allows the electrification of two-wheelers in Southeast Asia, three-wheelers in India, and affordable grid storage in Africa. We are moving from an era of “luxury energy” to “commodity energy,” where the storage medium is as common as the salt on a dinner table.

The Raw Material Reality (2026 Snapshot)

A comparison of the fundamental resource constraints driving the shift away from lithium exclusivity.

| Feature | Lithium-Ion (NMC/LFP) Supply Chain | Sodium-Ion Supply Chain | Strategic Implication |

| Primary Resource | Lithium Carbonate / Spodumene | Sodium Carbonate (Soda Ash) | Security: Sodium is globally available; Lithium is geologically concentrated. |

| Anode Collector | Copper Foil (Expensive, heavy) | Aluminum Foil (Cheap, light) | Cost: Sodium allows a 15-20% weight and cost reduction at the component level. |

| Cathode Materials | Nickel, Cobalt, or Lithium Iron Phosphate | Prussian Blue, Layered Oxides (Fe/Mn based) | Ethics: Sodium eliminates conflict minerals like Cobalt entirely. |

| Refining Control | China controls ~65-90% of global capacity | Distributed global chemical industry | Sovereignty: Nations can build domestic supply chains without importing refined ores. |

| Price Stability | High volatility (Boom/Bust cycles) | Flat commodity pricing | Planning: Automakers can forecast costs years in advance with Sodium. |

Western Sovereignty: The “Made in Not-China” Mandate

While Asian giants currently lead production, the West is aggressively using sodium-ion to build a “sovereign battery architecture.” The logic is simple: Europe and the US cannot beat China on lithium refining (where China controls ~70% of capacity), but they can compete on sodium, where the feedstock is universally available.

-

Europe’s “Tiamat” Strategy: France has taken a lead role with Tiamat, a spinoff from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). backed by Stellantis and Arkema. In early 2026, Tiamat broke ground on a 5GWh giga-factory in Amiens, Hauts-de-France. This facility is not just a factory; it is a statement of intent to build a battery supply chain entirely independent of non-European minerals.

-

The UK’s Strategic Bet: The UK has doubled down through its Faraday Battery Challenge. The recently announced £452 million “Battery Innovation Programme” (running 2026–2030) explicitly identifies sodium-ion as a critical technology for national energy security, funding projects to scale domestic “hard carbon” production from local biomass.

-

US Department of Energy (DOE) Action: The US has moved from observation to funding. Following the $15.7 million grant allocation in 2024, the DOE has expanded its “Battery Materials Processing” grants in 2026 to specifically favor non-lithium chemistries that use domestic feedstocks (like Wyoming soda ash), aiming to insulate the US grid from foreign supply shocks.

The Technology and Performance Reality: Beyond the Hype

While the economic argument is compelling, the technological reality of sodium-ion batteries in 2026 is nuanced. Early skepticism focused on the physical limitations of sodium ions. A sodium ion is significantly larger and heavier than a lithium ion (0.98 Ångströms radius versus 0.76 Ångströms). In the world of atomic physics, this size difference is massive. It creates sluggish diffusion kinetics—meaning the ions move slower—and causes greater mechanical stress on the cathode materials as the ions move in and out during charging cycles. For years, this resulted in batteries with poor energy density and short lifespans. However, the commercial cells rolling off production lines today have largely solved these “birthing pains” through advanced material science.

The current generation of commercial sodium-ion cells has settled on three primary cathode chemistries, each serving different market niches. The most prominent is the Layered Oxide approach, championed by companies like HiNa Battery, which offers a balance of energy density and ease of manufacturing because it mimics existing lithium-ion production processes. The second is Prussian Blue Analogues, a chemistry that offers incredibly fast charging and high cycle life but has struggled with moisture sensitivity in manufacturing. The third is Polyanion, which offers the highest safety and cycle life but lower voltage.

Despite these advancements, a clear performance gap remains. As of 2026, top-tier sodium-ion cells boast an energy density of roughly 160-175 Wh/kg. In isolation, this is respectable, surpassing the lead-acid batteries of the past. However, when compared to high-nickel lithium batteries that exceed 250 Wh/kg, sodium falls short for long-range applications. It is physically impossible, with current physics, to build a sodium-ion sports car with a 500-mile range without the battery pack becoming prohibitively heavy.

However, sodium-ion technology possesses a “killer feature” that lithium cannot match: Temperature Resilience. Lithium-ion batteries are notoriously temperamental, losing significant range and charging capability in freezing weather. This has been a major barrier to EV adoption in regions like Canada, Scandinavia, and the Northern United States. Sodium-ion electrolytes maintain high ionic conductivity even at low temperatures. A sodium-ion vehicle can sit in -20°C weather and retain over 90% of its range and, crucially, still accept a fast charge. This characteristic alone disrupts the market, suggesting that while lithium may own the “range” metric, sodium owns the “reliability” metric.

Furthermore, safety protocols for sodium are superior. Lithium-ion batteries must be transported with a 30% state of charge to prevent degradation, which leaves them energized and vulnerable to thermal runaway during shipping. Sodium-ion batteries can be discharged to literally zero volts. They can be shipped as inert blocks of metal and plastic, completely eliminating fire risk during logistics. This “zero-volt” capability also simplifies the Battery Management System (BMS) and allows for safer maintenance and recycling processes.

The 2026 Battery Battlefield (Cell Level Comparison)

Detailed technical trade-offs facing OEMs choosing between incumbent and challenger technologies.

| Technical Metric | Sodium-Ion (Gen 1.5 – 2026) | Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) | Lithium NMC (811) |

| Energy Density | 160 – 175 Wh/kg | 160 – 175 Wh/kg | 250 – 300 Wh/kg |

| Cycle Life | 4,000 – 6,000 Cycles | 6,000 – 10,000 Cycles | 2,000 – 3,000 Cycles |

| Cold Weather (-20°C) | Excellent: 90% Retention | Poor: ~50-60% Retention | Fair: ~70% Retention |

| Fast Charging (80%) | 15 Minutes (4C rate possible) | 20-30 Minutes | 15-20 Minutes |

| Transport Safety | 0V Discharge (Inert) | Risk of Thermal Runaway | High Risk |

| Sustainability | High (No Cobalt/Nickel/Lithium) | High (No Cobalt/Nickel) | Low (Requires Cobalt/Nickel) |

| Recycling Value | Low (Materials are cheap) | Low | High (Recoverable metals) |

Industrial Scale and Market Adoption: The Winners and Losers

The transition to sodium-ion is not happening in a vacuum; it is colliding with a mature, optimized, and ruthlessly efficient lithium-ion industry. This creates a fascinating Cost Paradox that characterizes the 2026 market. On paper, sodium-ion should be cheaper. The bill of materials suggests a cost floor 30% below lithium. However, the reality of manufacturing economics dictates otherwise. LFP battery production has benefited from decades of optimization, massive economies of scale, and supply chains that run like clockwork. Sodium-ion manufacturing is still in its adolescence. Rejection rates are higher, supply chains for battery-grade hard carbon anodes are still forming, and factory throughput is lower. Consequently, in early 2026, a sodium-ion cell actually costs more to buy ($59/kWh) than a mass-produced LFP cell ($52/kWh), which is currently suffering from global oversupply.

This paradox creates a “Valley of Death” that only the largest players can bridge. It explains why the market is dominated by giants like CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited) and BYD (Build Your Dreams). These conglomerates have the capital to run sodium production lines at a loss or break-even to build scale. They are implementing a “Dual-Star” or “AB Battery” strategy to force adoption. By designing battery packs that mix sodium cells and lithium cells in the same casing, they mask the lower energy density of sodium while gaining its cold-weather benefits. This strategy allows them to scale up sodium supply chains without forcing consumers to accept a low-range vehicle.

The market segmentation is becoming increasingly distinct. The “losers” in this shift are the pure-play lithium miners who banked on linear demand growth for lithium carbonate indefinitely. The “winners” are the diversified chemical giants producing soda ash and the automakers who can successfully integrate these lower-cost cells into entry-level vehicles. We are seeing a flood of “City EVs”—small, affordable hatchbacks—launching in Asian and European markets powered entirely by sodium. These vehicles do not need 500km of range; they need affordability and winter reliability.

Furthermore, the stationary grid storage market is the “sleeping giant” of sodium adoption. Grid storage installations do not care about weight (gravimetric density) or size (volumetric density) as much as they care about cost per cycle and safety. A battery installation in the basement of a skyscraper or a residential home prioritizes fire safety above all else. Sodium-ion’s superior thermal stability and ability to operate in wider temperature ranges (reducing the need for expensive HVAC cooling systems in battery containers) make it the eventual heir to the grid storage throne, likely displacing LFP by the late 2020s.

Comparative Cost Dynamics (The Path to Parity)

Projecting the economic crossover point where Sodium becomes the undisputed value leader.

| Cost Component | 2026 Status (Current) | 2028 Projection (Scaled) | The Driving Factor |

| Cathode Cost | Sodium is 20% cheaper | Sodium is 50% cheaper | Maturation of Prussian White/Blue supply chains. |

| Anode Cost | Sodium is Higher | Parity / Lower | Hard Carbon production is currently the bottleneck but scaling fast. |

| Current Collectors | Sodium is 60% cheaper | Sodium is 60% cheaper | Immediate savings from using Aluminum instead of Copper. |

| Manufacturing Overhead | Sodium is Higher | Parity | Learning curve improvements in yield and throughput. |

| Total Cell Cost ($/kWh) | Sodium: ~$59 vs. LFP: ~$52 | Sodium: ~$40 vs. LFP: ~$48 | Scale efficiencies overcome initial inefficiencies. |

The Regulatory Green Light: UN Codes 3551 & 3558

A critical but often overlooked enabler of the 2026 boom is regulatory legitimacy. Until recently, global shipping regulations didn’t have a specific category for sodium batteries, forcing them into a regulatory gray zone that made insurance and logistics difficult.

That changed on January 1, 2026, when the new United Nations “Orange Book” regulations went into full effect. The UN introduced specific transport codes—UN 3551 (Sodium-ion batteries) and UN 3558 (Sodium-ion battery-powered vehicles).

Why does this matter?

-

Legitimacy: It officially recognizes sodium-ion as a distinct class of dangerous goods, standardizing safety testing (UN 38.3) for international trade.

-

The “Zero-Volt” Loophole: Crucially, these new regulations acknowledge the unique ability of sodium-ion batteries to be shipped at 0% State of Charge (SoC). Unlike lithium batteries, which are classified as Class 9 Dangerous Goods and must be shipped with a 30% charge (creating fire risk), completely discharged sodium batteries can be transported as general cargo in many jurisdictions. This slashes logistics costs by removing the need for explosion-proof containers and expensive hazardous materials insurance, giving sodium a silent economic advantage in the global export market.

Future Outlook and Strategic Implications: The Road to 2030

Looking ahead, the mainstreaming of sodium-ion batteries signals the end of the “monolithic” battery market. We are moving toward a diversified ecosystem where chemistry is matched to the use case. The notion that one battery type must rule them all is obsolete. By 2030, analysts predict a “20-40-40” split: 20% of the market will remain high-nickel lithium (for luxury/performance/aviation), 40% will be LFP (for standard range mass-market EVs), and 40% will be Sodium-ion (for entry-level EVs, micro-mobility, and the vast majority of grid storage).

The next technical frontier is the Solid-State Sodium Battery. Research is already pivoting toward using solid electrolytes with sodium anodes. Because sodium metal is softer than lithium, it maintains better contact with solid electrolytes, potentially solving the interface issues that have plagued solid-state lithium research. If successful, this would boost sodium’s energy density to match current lithium levels while retaining its cost and safety advantages, effectively rendering liquid lithium-ion batteries obsolete for all but the most niche applications.

Environmentally, the shift is a net positive but introduces new challenges. While we reduce our dependence on lithium mining—which is water-intensive—scaling up hard carbon anodes (derived from biomass, coal, or resin) requires careful environmental management to ensure it does not become a new source of pollution. Additionally, the recycling industry, currently geared entirely toward recovering high-value cobalt and nickel, faces a crisis of profitability. Recycling a sodium-ion battery yields very little value because the materials are so cheap. Governments will likely need to mandate recycling or subsidize it, as the free market may not find it profitable to reclaim soda ash and iron.

Ultimately, the events of 2026 will be remembered as the moment the energy transition became “democratized.” By severing the link between energy storage and scarce minerals, sodium-ion technology ensures that the renewable energy revolution is not limited by the geology of the Andes or the refining capacity of East Asia. It turns energy storage into a manufacturing problem rather than a mining problem—and manufacturing problems are always solved by scale.

Key Players & Strategic Posture (2026)

Who is leading the charge in the Sodium revolution.

| Company | Origin | 2026 Operational Status | Strategic Focus |

| CATL | China | Mass Production | The “Dual-Star” Hybrid Pack (mixing Li and Na cells) for passenger vehicles. |

| BYD | China | Mass Production | Vertical integration; using Sodium in the “Seagull” and affordable lineup. |

| Northvolt | Sweden | Pilot / Scaling | Developing 160 Wh/kg cells specifically for European grid storage sovereignty. |

| HiNa Battery | China | Market Leader | Partnered with JAC Motors; delivered the first commercially available Sodium EV fleet. |

| Faradion | UK/India | Scaling | Acquired by Reliance; focusing on the massive Indian 2/3-wheeler and grid market. |

| Tiamat | France | Pilot | Focusing on high-power applications and hybrid vehicles (HEVs). |