For millions of people living with diabetes, checking blood sugar levels is a daily necessity — and often an uncomfortable one. Most diabetic patients rely on finger-prick tests, which require puncturing the skin with a small needle to collect a drop of blood. Although this method is standard, many patients find it painful, inconvenient, and difficult to perform multiple times a day. As a result, many individuals do not monitor their glucose levels as often as recommended, increasing the risk of serious health complications.

To address this long-standing problem, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a breakthrough technology that could eliminate the need for needles entirely. Their new device measures blood glucose levels using light waves instead of drawing blood, offering the possibility of a painless and more comfortable alternative. The findings were recently published in the journal Analytical Chemistry, highlighting the potential of this innovation to transform diabetes care.

How the Needle-Free Sensor Works Using Light Waves Instead of Blood

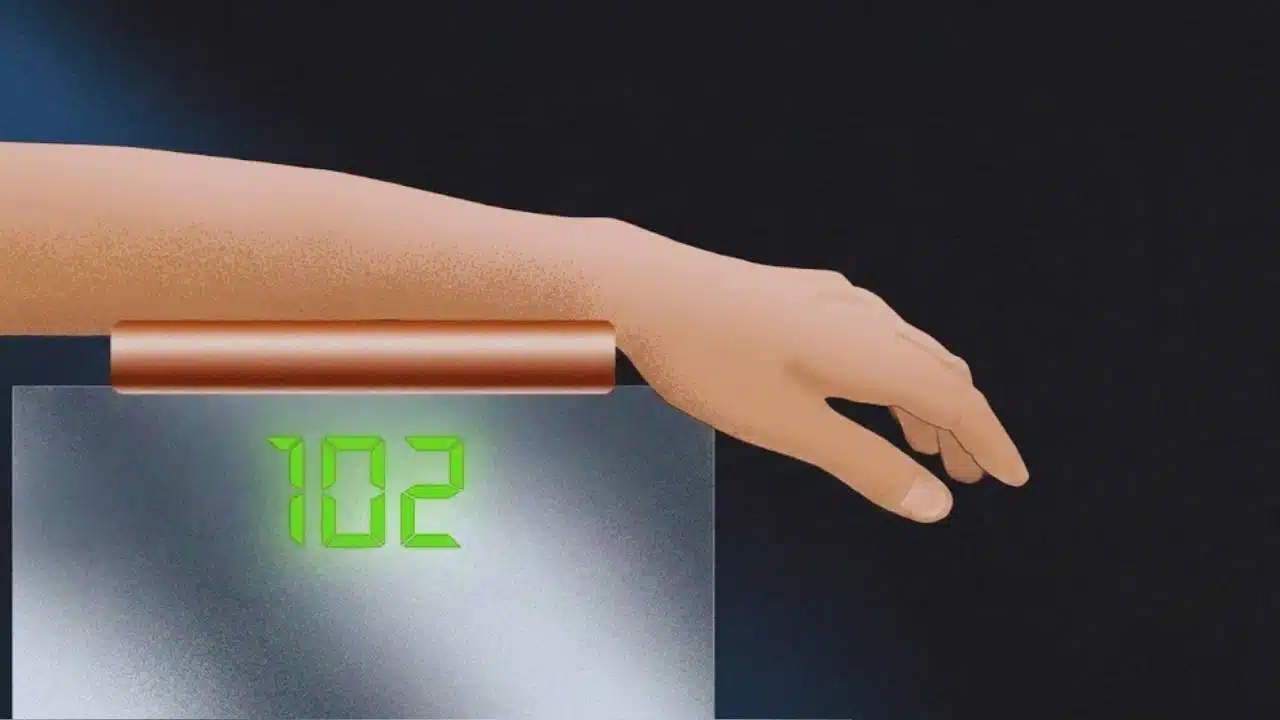

The core of this innovation lies in a scientific method known as Raman spectroscopy. This technique uses light — not needles — to gather information about molecules inside the body. When light from the device touches the skin, it scatters in specific patterns based on the molecules present beneath the surface. Glucose, the sugar molecule crucial to diabetes management, produces a unique pattern, allowing the device to identify a person’s blood sugar level simply by analyzing the scattered light.

This technology is the result of more than 15 years of research and refinement. The first major demonstration came in 2010, when engineers at MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center proved that Raman spectroscopy could, in theory, measure glucose levels without needing blood samples. Early prototypes were large, complex, and not practical for patients. The signals of glucose were also difficult to separate from the signals of other molecules in the skin.

Over time, researchers found ways to make the signals clearer and more reliable. In 2020, MIT scientists made significant progress by shining near-infrared light from different angles to isolate glucose signals more effectively. This improvement allowed the device to filter out biological “noise,” making the glucose information much more accurate.

The latest version of the sensor focuses on three key bands of light signals instead of the full spectrum, which greatly increases both speed and accuracy. Today, the device can provide a reading in about 30 seconds — a dramatic improvement from earlier models that required longer time and more complex equipment.

From Printer-Sized Machines to a Shoebox-Sized Device

One of the major challenges in developing non-invasive glucose monitoring has been reducing the size of the device. Early prototypes were almost as large as a desktop printer and suitable only for laboratory use. After years of engineering advancements and material improvements, the latest version is about the size of a shoebox — still not pocket-sized, but far more convenient and practical than before.

Researchers involved in the project emphasized that the current milestone is just the beginning. They aim to shrink the device even further, eventually creating a portable tool that patients could use anywhere, much like current handheld glucometers. Some team members believe that future versions may even become wearable, allowing continuous glucose monitoring without any invasive components.

A Major Step Toward Comfortable and Consistent Diabetes Care

Experts involved in the project highlight that the biggest advantage of this technology is comfort. As scientist Jeon Wong Kang explains, no one wants to prick their finger multiple times a day. It is painful, inconvenient, and discourages people from checking their glucose regularly. Reduced monitoring can lead to dangerous spikes or drops in blood sugar levels, increasing the likelihood of long-term complications such as nerve damage, kidney disease, and vision loss.

By offering a painless alternative, this light-based device has the potential to help diabetic patients monitor their health more consistently and confidently. Although further clinical testing is needed before the device becomes widely available, the scientific progress is a promising step toward a future where diabetes management is easier, safer, and needle-free.