It was sometime in the late 2010s, and I found myself on a long, exhausting road trip with my wife and our two children. We’d been driving for more than six hours, and as we neared the end of our journey, traffic came to a grinding halt. Another unexpected delay. Another frustrating setback. I lost my temper. F-bombs flew freely as my irritation evolved into outright fury. When my wife gently asked if I wanted her to drive, I snapped back, rejecting the offer.

The atmosphere in the car shifted immediately. My children went completely silent in the back seat, frightened by the sudden explosion. My wife fell quiet too, not wanting to provoke me further. In that tense moment, they were all emotionally hostage to my rage. They didn’t say a word—not because they didn’t want to—but because they were scared of escalating the anger.

Years later, that memory came rushing back while watching the final episode of Adolescence, a powerful British drama streaming on Netflix. The show delivers a raw and unflinching portrayal of how male rage traps families in fear—something I know all too well.

The Miller Family: A Mirror for Modern Male Rage

The final episode of Adolescence captures an eerily similar scenario. Thirteen-year-old Jamie Miller (played with quiet intensity by Owen Cooper) has stabbed a classmate to death, and the ripple effect of that violence is felt most sharply by his family. In one particularly devastating scene, Jamie’s father Eddie (portrayed by the brilliant Stephen Graham) is driving with his wife Manda (Christine Tremarco) and daughter Lisa (Amelie Pease) when he breaks down emotionally. He starts screaming, pounding the steering wheel as grief, guilt, and frustration erupt all at once.

Manda and Lisa don’t say a word. They sit next to him in petrified silence, mirroring my own family’s reaction years ago. The camera doesn’t cut. It doesn’t allow the viewer to escape. We’re stuck in that car too, trapped alongside Eddie and his family.

A Gutsy Creative Choice: One-Shot Episodes as Emotional Entrapment

Directed by Philip Barantini, each episode of Adolescence is filmed as a single uninterrupted shot. It’s a risky stylistic choice—but an incredibly effective one. It forces the audience to endure each claustrophobic scene in real-time, without the relief of editing cuts or shifts in perspective. You can’t blink. You can’t look away.

Barantini locks us in with the Miller family as police burst into their home in the first episode. He traps us inside the chaotic halls of Jamie’s high school as detectives comb for answers in the second. In the third, he confines us to a sterile juvenile detention center, where a psychologist (played by Erin Doherty) attempts to assess Jamie—only to be met with his explosive outbursts.

Each episode centers on women who are placed in proximity to male rage. They are not the perpetrators, but the victims and emotional shock absorbers. That dynamic is uncomfortably familiar. Rage is not just a personal issue—it becomes a collective trauma for those forced to witness or endure it.

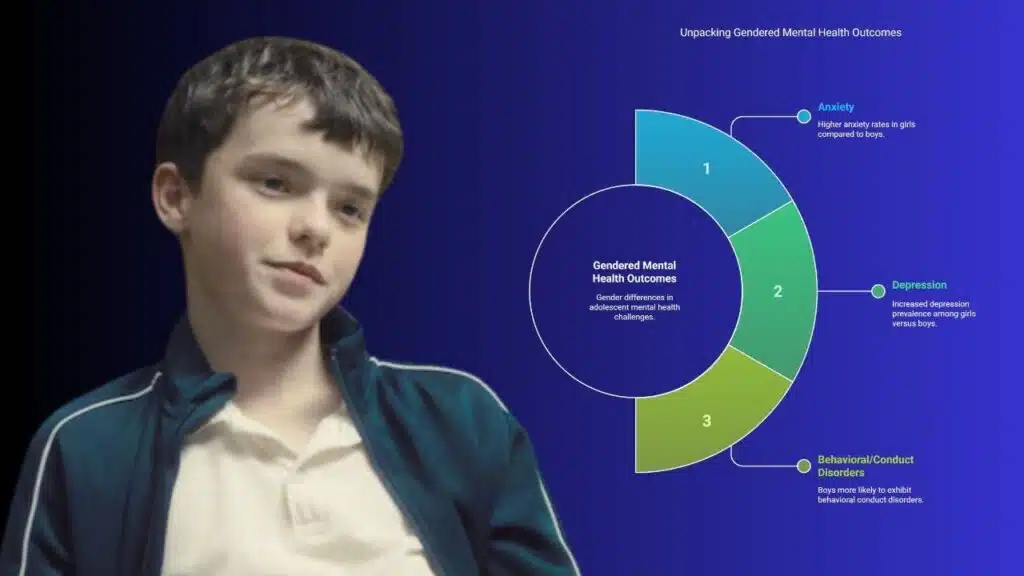

A Gendered Crisis: What the Numbers Say

The emotional weight of Adolescence is backed by real data. A U.S. study released by the Biden administration in 2023 highlighted a troubling gender divide in mental health diagnoses:

- Anxiety: 20.1% of girls vs. 12.3% of boys

- Depression: 10.9% of girls vs. 6.0% of boys

- Behavioral/Conduct Disorders: 8.2% of boys vs. 4.3% of girls

You can draw a direct line between these numbers. Boys are statistically more likely to act out with aggression and impulsive behavior, while girls are more likely to internalize that trauma, leading to anxiety and depression. As Adolescence shows us, male rage often triggers a silent emotional crisis in those around them—usually women and children.

I’ve seen it in my own life. I’ve unintentionally created emotional turbulence in my home through unmanaged anger. Watching Adolescence felt like holding up a mirror to my past self—and it was deeply uncomfortable.

Rage Is Not Entertainment—It’s a Warning

There’s a cultural narrative that celebrates rage, particularly when it comes from men. Think about it:

- The climax of an action movie? When the hero finally snaps and kills the villain.

- The best moment in a war film? When the soldier avenges a fallen comrade in a blood-soaked fury.

- Even in comedy—like Adam Sandler films—the funniest moments often stem from him losing his temper in absurd, over-the-top ways.

Our media tells us that rage is power. That it’s righteous. That it solves problems.

But Adolescence tears that fantasy apart. Rage is not cathartic. It’s not noble. It’s destructive, senseless, and contagious. The series offers no glamorization—only consequences. Every time a man yells, slams a door, or throws something across a room, the people around him flinch. They freeze. They strategize how to de-escalate. That’s not drama—that’s trauma.

The Violence You Don’t See

Unlike many crime dramas, Adolescence never shows the murder. There are no graphic reenactments. We don’t see the stabbing. Jamie doesn’t confess to it in dramatic detail. Even the court psychologist doesn’t pull the full story out of him. The show withholds all of that on purpose.

Because the real story isn’t the act of violence—it’s everything around it. The culture that raised Jamie. The broken family dynamics. The internet forums filled with incel ideologies and toxic masculinity. The warning signs that adults missed. The rage that grew quietly until it exploded.

Director Philip Barantini made this creative decision intentionally, explaining in interviews that Adolescence is not a whodunit—it’s a psychological dissection. “Really what it’s about,” he said, “is looking at male rage and looking at our own anger and looking at who we are as men.”

The Silent Epidemic of Emotional Suppression

I saw myself in Jamie. I saw myself in Eddie. I’ve never physically harmed anyone, but I’ve screamed. I’ve punched pillows and slammed doors. I’ve scared my family—not intentionally, but that’s what rage does. It hijacks your emotions and imposes fear on everyone in its path.

I’ve even raged online. I’ve had imaginary arguments with my wife in my head, always casting myself as the rational one with the upper hand. I didn’t see it as a problem until my wife sat me down after that road trip and said, “Get your s—t together, or we’re driving separately from now on.”

That was the wake-up call I needed. I got help. Therapy. Medication. Open conversations with my family. But it took me years to get to that point. What happens to men who never reach that moment of clarity? What happens when we normalize this rage instead of confronting it?

Adolescence as Cultural Mirror

In an era where school shootings, domestic violence, and radicalized young men are frequent headlines, Adolescence feels brutally timely. Netflix reports that the show has reached tens of millions of viewers, becoming one of the most-watched limited series of the year. And unlike many “issues-based” dramas that feel preachy or contrived, Adolescence never veers into moralizing territory.

It doesn’t offer easy answers. It doesn’t give you a villain to hate or a victim to pity. It blurs the lines on purpose, showing that the roots of rage are tangled in neglect, pain, societal conditioning, and emotional isolation.

Writers Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham, along with Barantini, resisted the urge to explain Jamie away. They didn’t give him a backstory that absolves him. They didn’t show the murder as a moment of madness or make him a monster. They made him human—and that’s what makes it all the more terrifying.

Adolescence is not easy to watch, but it’s essential viewing. It’s not about a crime—it’s about a crisis. One that affects families, schools, workplaces, and society at large.

I came away from it unsettled, reflective, and—most of all—grateful. Grateful that I got help. Grateful that I learned to listen before I yelled. Grateful that I had a partner who cared enough to confront me. But I also came away worried. Worried about the men who never reach that point. Worried about the boys growing up now who are being taught, once again, that rage is strength and silence is safety.

The Information is Collected from WSJ and Daily Mail.