Each October, the world turns its attention to Stockholm and Oslo as a series of phone calls announce the newest members of an elite club: the Nobel laureates. For over 120 years, these prizes have been celebrated as the ultimate recognition of human intellect and altruism. Yet, in our rapidly changing world—defined by global collaboration, digital innovation, and a reckoning with historical injustices—a pressing question has gained significant traction: Is the Nobel Prize still relevant today?

While the prize continues to capture global imagination and confer unparalleled prestige, it is increasingly scrutinized for its secretive selection process, its slow adaptation to modern science, and a persistent diversity deficit that challenges its claim to be a universal arbiter of excellence.

The fundamental mission of the Nobel Prize, established in the will of Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, is to honor those who have “conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.” This noble ideal is the bedrock of its continued significance. The awards serve as a powerful global megaphone, amplifying groundbreaking scientific discoveries and vital humanitarian work that might otherwise remain obscure. As detailed on the Nobel Prize’s official website, laureates’ achievements have reshaped our understanding of the universe and improved the human condition in countless ways.

However, the 21st century brings new complexities. Modern scientific breakthroughs are often the result of massive international teams, making the Nobel’s rule of a maximum of three winners per prize seem archaic. Moreover, persistent criticism regarding Eurocentrism and a historical bias against women and people of color has led many to question whether the prize truly reflects the global landscape of innovation and progress.

The Secretive Path to a Nobel Prize

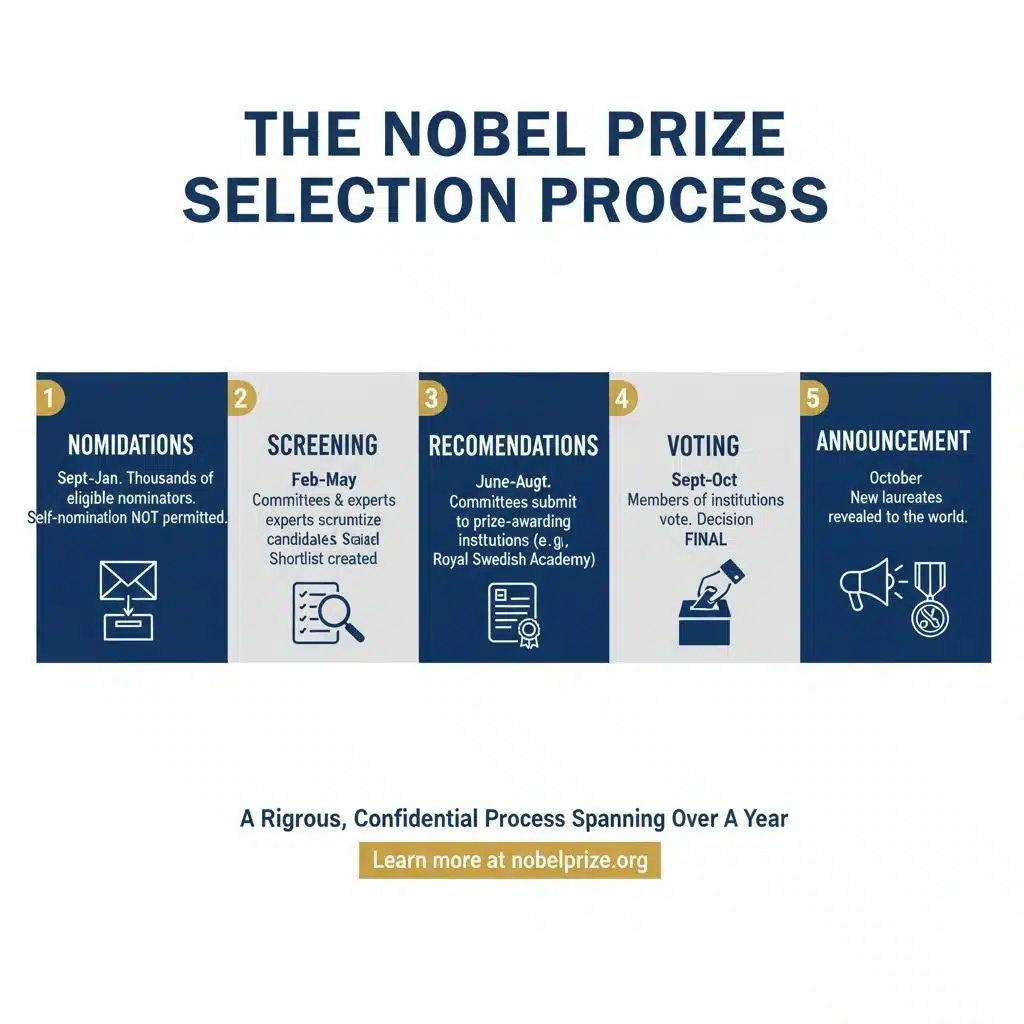

Before weighing its relevance, it is crucial to understand the notoriously opaque process behind selecting a laureate. Unlike public awards, the Nobel journey is shrouded in secrecy for 50 years.

Nomination and Selection: A Confidential Process

The process begins in September each year, nearly a full year before the announcements. The various Nobel Committees send out thousands of confidential nomination forms to a select group of individuals. These nominators typically include members of national academies, university professors in relevant fields, previous Nobel laureates, and members of certain international bodies.

Key stages of the selection process include:

- Nominations (September-January): Thousands of eligible nominators submit their candidates. Self-nomination is not permitted.

- Screening (February-May): The Nobel Committees, with the help of specially appointed experts, scrutinize the nominated candidates and prepare a shortlist.

- Recommendations (June-August): The committees submit their final recommendations to the prize-awarding institutions (e.g., the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for Physics and Chemistry).

- Voting (September-October): The members of these institutions vote to select the laureates. The decision is final and cannot be appealed.

- Announcement (October): The names of the newly minted Nobel laureates are announced to the world.

This rigorous, multi-stage process is designed to ensure that the prize is awarded only after extensive expert consultation. However, the complete secrecy—with nomination details kept under lock and key for half a century—also fuels speculation and criticism about who gets overlooked and why.

The Enduring Glow: Why the Nobel Still Matters

Despite valid criticisms, the Nobel Prize continues to wield immense influence. Its prestige remains a powerful force for good, providing laureates with a unique platform to advance their work and inspire global change.

A Catalyst for Scientific Progress and Public Understanding

The Nobel Prize is unparalleled in its ability to translate complex scientific concepts for the public. When a discovery wins the Nobel, it becomes front-page news, sparking curiosity and promoting scientific literacy. The 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for their discoveries concerning mRNA, is a perfect illustration. Their foundational research enabled the rapid development of highly effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19. As highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO), these vaccines were critical in combating the pandemic, saving millions of lives. The Nobel Prize not only honored Karikó and Weissman but also educated the global public on the power of this new vaccine technology.

Championing Human Rights and Diplomacy

The Nobel Peace Prize, in particular, acts as a moral compass, shining a light on urgent human rights crises and honoring those who risk everything for peace. It often sends a powerful political message. For instance, the 2022 prize was awarded jointly to human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski from Belarus, the Russian human rights organization Memorial, and the Ukrainian human rights organization Center for Civil Liberties. In the midst of the war in Ukraine, the Norwegian Nobel Committee stated this prize was intended to honor “three outstanding champions of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence,” a clear condemnation of authoritarianism and a celebration of civil society in the face of conflict. Similarly, the 2023 prize awarded to Narges Mohammadi for her fight against the oppression of women in Iran brought global attention to her imprisonment and the courageous “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement.

Shadows in the Hall of Fame: The Criticisms Deepen

The reverence for the Nobel is increasingly challenged by deep-seated issues that the institution has been slow to address, undermining its claim to be a modern and impartial award.

The Persistent Diversity Deficit

The most glaring flaw of the Nobel Prize is its historical and ongoing lack of diversity. The numbers paint a stark picture of an institution that has overwhelmingly favored white men from Europe and North America.

| Category | Total Individual Laureates (1901-2023) | Women Laureates | Percentage of Women |

| Physics | 224 | 5 | 2.2% |

| Chemistry | 192 | 8 | 4.2% |

| Physiology or Medicine | 227 | 13 | 5.7% |

| Literature | 120 | 17 | 14.2% |

| Peace | 111 | 19 | 17.1% |

| Economic Sciences | 93 | 3 | 3.2% |

| Total | 967 | 65 | 6.7% |

Source: The Nobel Foundation, as of October 2023.

This imbalance means the prize has failed to recognize many monumental contributions. Scientists like Rosalind Franklin, whose X-ray diffraction images were critical to discovering the structure of DNA, and Lise Meitner, a key figure in the discovery of nuclear fission, were famously overlooked. The Nobel Foundation has acknowledged this issue, with Göran Hansson, former Secretary General of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, telling Nature that they are actively encouraging nominating bodies to consider diversity, but the results have been slow to materialize.

An Outdated Framework in a Modern World

Alfred Nobel’s will defined the prize categories in 1895, and they have barely changed since. This rigid structure is ill-suited to the 21st century’s scientific landscape.

- Ignoring Key Fields: Crucial disciplines like environmental science, artificial intelligence, and mathematics have no dedicated Nobel Prize. While the Fields Medal is often called the “Nobel for mathematics,” the lack of a Nobel category for these world-changing fields is a significant blind spot.

- The Three-Person Limit: Modern science is profoundly collaborative. Groundbreaking projects like the discovery of gravitational waves in 2015 by the LIGO collaboration involved over 1,000 scientists. Yet, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics could only be awarded to three of its leaders, leaving hundreds of key contributors unrecognized.

Mired in Political and Ethical Controversy

The Peace and Literature prizes have often been at the center of fierce debates. The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to controversial figures like Henry Kissinger in 1973, even as the Vietnam War raged on. More recently, Barack Obama’s 2009 prize, awarded less than a year into his first term, was seen by many, including Obama himself, as premature.

The Swedish Academy, which awards the Literature Prize, has also faced major crises. In 2018, the prize was postponed following a sexual assault and financial misconduct scandal, as extensively reported by news outlets like The Guardian. Such events damage the prize’s integrity and raise questions about the judgment of the awarding committees.

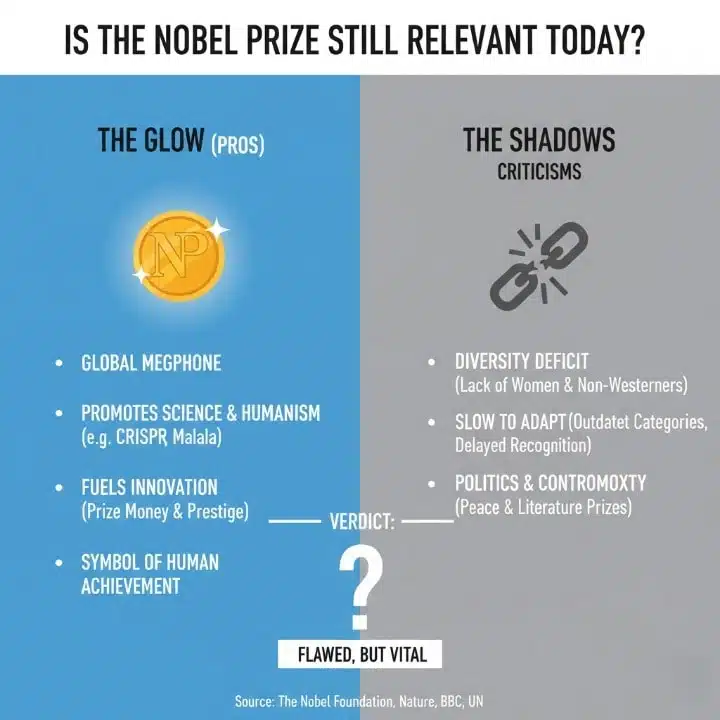

The Verdict: A Flawed but Vital Institution

So, to return to the central question: Is the Nobel Prize still relevant today? The answer is a resounding, if complicated, yes. The institution is flawed, carrying the baggage of 20th-century biases and a structure that struggles to keep pace with the modern world. The criticisms regarding its diversity, its anachronistic categories, and its political controversies are not just valid; they are vital for pushing the Nobel Foundation toward necessary reform.

However, to declare it irrelevant would be to ignore its unique and immense power. No other award commands the same level of global attention or possesses the same ability to elevate ideas and individuals onto the world stage. It remains a powerful symbol of human potential, a celebration of the relentless pursuit of knowledge and peace. The Nobel Prize forces us, at least once a year, to pause and reflect on the “greatest benefit on mankind.”

In conclusion, the Nobel Prize is at a crossroads. Its future relevance hinges on its ability to evolve—to become more inclusive, more agile, and more reflective of the globalized, collaborative world it seeks to honor. The ongoing debate about Is the Nobel Prize still relevant today? is perhaps the best proof of its enduring importance. It shows that we still care deeply about recognizing and celebrating the very best of humanity.