You know how we obsess over the latest hardware specs or the newest game engine? We assume “newer” always means “better.” But if you look at the Earth as a complex operating system, you realize something uncomfortable. The modern patches we’ve released over the last century are buggy. They cause overheating (literally) and system crashes. Meanwhile, there is a legacy code that has been running with 100% uptime for thousands of years. That code is Indigenous Knowledge.

When I look at how Indigenous communities manage land, I don’t see “ancient history.” I see a highly optimized, open-source system that balances resource load perfectly. From the Menominee Forest in Wisconsin to the Yurok lands in California, these communities aren’t just surviving nature. They are engineering resilience.

This isn’t about going backward. It is about recovering the admin access we lost. I want to walk you through the specific “mechanics” of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and show you how it is outperforming modern tech in the fight against climate change. Let’s look at the data.

Understanding Indigenous Knowledge as a “Legacy System”

Indigenous knowledge is often treated like folklore, but that is a mistake. You need to view it as a dataset built on thousands of years of A/B testing. While modern science relies on short-term studies, TEK relies on generational observation. It is the difference between a beta test and a stable release.

Definition and characteristics of Indigenous knowledge

Traditional Ecological Knowledge is a cumulative body of knowledge. It evolves. Just like a machine learning algorithm refines itself with new data, TEK adapts to every shift in animal migration or weather patterns. It is passed down through stories and hands-on practice, ensuring the “source code” remains accurate across generations.

The land is our teacher, says many Elders who pass down lessons on climate resilience.

The connection between Indigenous communities and the environment

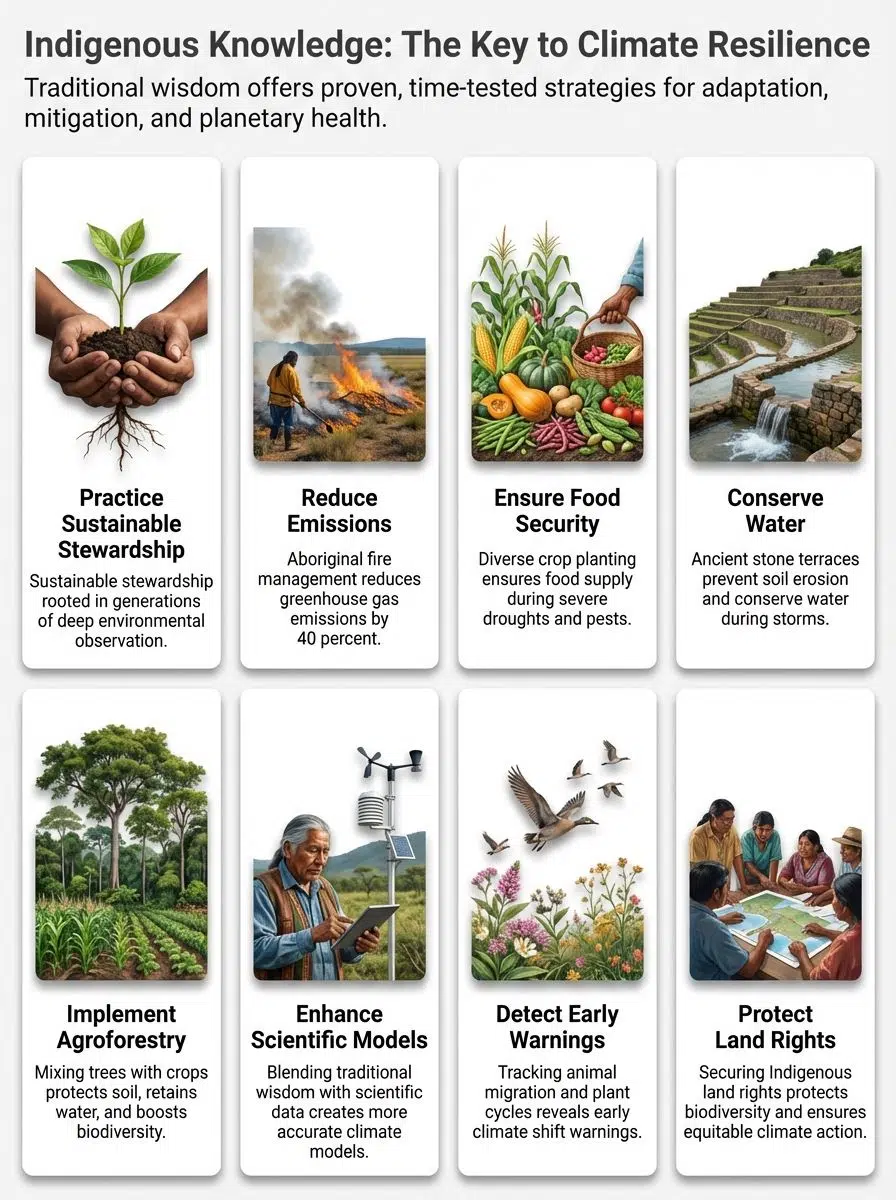

In the US, the most stunning example of this system in action is the Menominee Forest in Wisconsin. If you look at satellite imagery of the state, you can actually see the reservation outline. It is a dark green block of dense forest in a sea of lighter, cut-over farmland. This isn’t an accident. It is the result of a specific management logic.

The Menominee people have harvested over 2.25 billion board feet of timber since 1854. That is a massive amount of resource extraction. Yet, here is the kicker: the volume of standing timber in their forest is actually higher today than it was 170 years ago. They didn’t just preserve the forest; they engineered a way to use it without depleting it. They cut the weak trees to let the strong ones grow, which is the exact opposite of the “high-grading” (taking the best trees) common in commercial logging.

This proves that human activity doesn’t have to be a virus for the ecosystem. If you run the right script, humans can be the immune system. Their actions protect biodiversity and boost Climate Resilience across regions facing harsh threats today.

Indigenous Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation

When the climate starts glitching, droughts, floods, and heatwaves, local experts spot the lag long before the official reports come out. Adaptation is about having a flexible system that can handle stress without crashing.

Observation of climate impacts through local knowledge

Farmers and fishers operate on the front lines. They notice when the “textures” of the world don’t load right. In Alaska, Indigenous hunters have documented shifts in sea ice thickness that satellite data initially missed. They track changes in rain patterns by watching streams shrink or swell. These aren’t guesses. They are data points gathered from daily interaction with the hardware of the planet.

The earth talks if you know how to listen, shares an elder from a southwestern tribe.

Traditional farming and water management practices

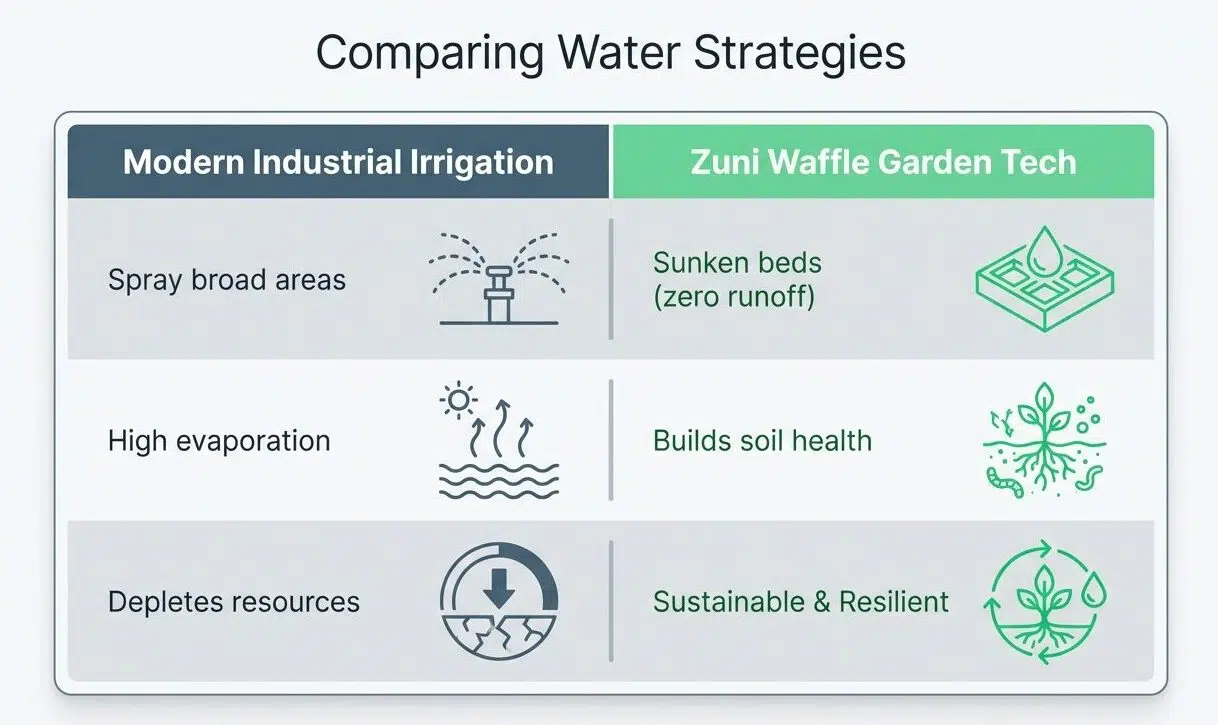

Let’s look at a specific mechanic for water conservation: the Zuni Waffle Garden. In New Mexico, the Zuni people developed a method that makes modern sprinkler systems look incredibly wasteful. Instead of planting in rows that let water run off, they create a grid of sunken square beds surrounded by clay walls. It looks exactly like a waffle.

This structure creates a microclimate for each plant. The walls provide shade and block the drying wind. The sunken bed holds every drop of rain or hand-poured water right at the roots. There is zero runoff. In a region where water is the scarcest resource, this design is pure efficiency.

Comparing Water Strategies

| Feature | Modern Industrial Irrigation | Zuni Waffle Garden Tech |

| Water Logic | Spray broad areas (high evaporation)

|

Sunken beds (zero runoff)

|

| Soil Impact | Often leads to erosion and salt buildup

|

Builds soil health and retains moisture

|

| Resilience | Fails without a massive external water supply

|

Functions effectively in extreme drought

|

Drought-resistant crops and sustainable land use

Farmers in Indigenous communities often choose crops that stand up well to hot and dry weather. The Hopi people of Arizona plant corn deep, sometimes a foot down, to reach residual soil moisture. This isn’t standard farming; it is extreme adaptation. They aren’t trying to force the land to support a generic crop. They are selecting the right “software” for the specific “hardware” of the desert.

Indigenous Knowledge in Climate Change Mitigation

Mitigation is about reducing the damage. It is about patching the security holes. Indigenous communities have been doing this through active management that prevents catastrophic failures like megafires.

Nature-based solutions like agroforestry

Agroforestry mixes trees with crops. It is like running multiple applications on the same server to maximize performance. Trees protect the soil and keep the air cool. This method bounces back faster from storms. It creates a redundancy in the food system. If one crop fails, the nuts or fruits from the trees might still provide.

Low-impact building and resource management techniques

In the tech world, we talk about “thermal throttling” when a system gets too hot. Indigenous architecture mastered thermal management centuries ago. Pueblo structures in the Southwest use thermal mass (adobe/stone) to absorb heat during the day and release it at night. No air conditioning required. In northern Canada, Inuit snow houses trap heat with incredible efficiency.

Community-led conservation initiatives

The most critical mitigation strategy right now is Cultural Burning. For decades, federal policy in the US was “fire suppression”, basically, put out every fire immediately. We now know this was a fatal system error. It allowed fuel to build up, turning healthy forests into ticking time bombs.

Tribes like the Yurok and Karuk in California are leading the way in bringing “good fire” back. They use low-intensity, controlled burns to clear out the underbrush. This prevents the high-intensity wildfires that destroy everything.

- Fuel Reduction: Burning the scrub prevents fire from climbing into the tree canopy.

- Carbon Storage: A healthy, large tree stores more carbon than a forest of dead, burnt matchsticks.

- Cultural Revival: In 2024, the Yurok Tribe signed a historic agreement to co-steward ‘O Rew (a 125-acre redwood property), proving that state agencies are finally recognizing that the original fire managers knew what they were doing.

Integration of Indigenous Knowledge with Modern Science

We are finally seeing a “merger” of these two operating systems. It is not about replacing science; it is about upgrading it with better data.

Bridging traditional practices with Western scientific approaches

There is a concept called “Two-Eyed Seeing” (Etuaptmumk). It means looking at the world with one eye on Indigenous wisdom and the other on Western science. In 2024, Acadia National Park in Maine applied this approach to protect coastal archaeological sites from rising sea levels. They combined satellite data with the oral histories of the Wabanaki people to identify which areas were most at risk.

Another example is the use of LiDAR technology by tribes to map ancestral terrace systems or water channels. They are using high-tech tools to validate and restore ancient engineering.

Contributions to global climate policies

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has officially recognized TEK as a key driver for climate resilience. This is a major policy patch. It admits that local observations are peer-reviewed by centuries of survival.

Examples from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

The IPCC’s 2022 Sixth Assessment Report didn’t just mention Indigenous knowledge as a footnote. It highlighted it as a primary tool for adaptation. They noted that Indigenous land tenure often overlaps with the highest biodiversity areas. Essentially, where Indigenous rights are respected, the “system health” of the planet is higher.

Challenges in Leveraging Indigenous Knowledge

Despite the clear benefits, we have compatibility issues. The legacy of colonialism acts like malware that corrupted the files and locked out the admins.

Impacts of rapid environmental changes on traditional practices

Climate change is happening so fast that it is outpacing the “update cycle” of traditional knowledge. Seasons are shifting. The cues that elders rely on, like when a certain flower blooms signaling the salmon run, are falling out of sync. This latency makes it harder to apply traditional methods without rapid adjustment.

Recognizing and addressing the legacy of colonialism

You cannot talk about this without addressing the ban on cultural practices. For over a century, the US government legally prohibited tribes from burning their own land. This policy directly contributed to the wildfire crisis we face today. Restoring these rights is not just a social justice issue; it is a public safety requirement.

Need for equitable climate policies that respect Indigenous rights

This brings us to Data Sovereignty. Who owns the knowledge? In the tech world, we fight for user privacy. Indigenous communities are fighting for the CARE Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics). This framework ensures that when scientists use Indigenous data, they don’t just extract it and sell it. The communities must retain “admin rights” to their own intellectual property.

Benefits of Indigenous Knowledge in Climate Action

So, what is the ROI (Return on Investment) of integrating this knowledge?

Enhancing resilience and sustainability

The data is clear: Indigenous peoples manage about 20% of the Earth’s land, but that land holds 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. That is an incredibly efficient ratio. If you want to save the “files” (species) from being deleted, you need to support the people who manage the “server” (the land).

Improving the accuracy of climate data through local observations

Local observers catch the edge cases that models miss. In the Arctic, Inuit communities provide real-time updates on ice conditions that keep climate models honest. This ground-truthing is essential for accurate predictions.

Promoting equity and inclusivity in climate solutions

When you include Indigenous leaders in the decision-making process, you get solutions that actually work on the ground. It moves us away from top-down theoretical fixes and toward practical, community-based patches that hold up under pressure.

Wrapping Up

We need to stop looking for a high-tech savior to fix the climate crisis. The most advanced technology for planetary management isn’t a carbon capture machine; it is the cultural framework that kept the Menominee forest standing for 170 years. It is the logic of the Zuni waffle garden.

Indigenous knowledge offers a proven roadmap for sustainability. It is time we stop trying to overwrite this system and start learning how to run it. Whether you are a gamer, a gardener, or just someone trying to survive the next heatwave, there is a lesson here: respect the legacy code. It might just save us all.