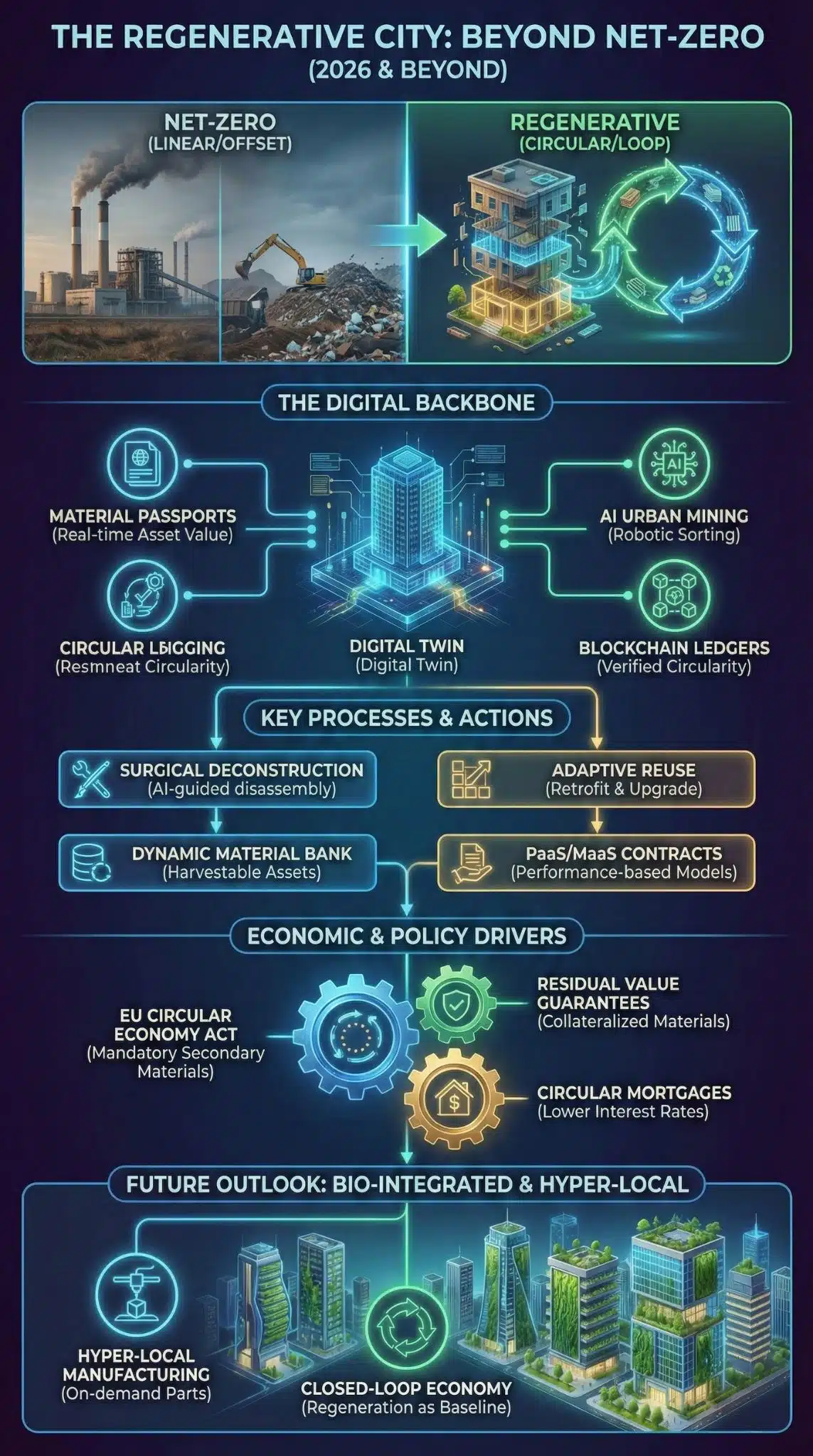

While net-zero targets dominated the early 2020s, 2026 marks the definitive pivot to circularity. Driven by critical mineral shortages and the enforcement of the EU’s Circular Economy Act, urban development is shifting from merely offsetting emissions to active resource regeneration through AI-driven urban mining and digital material banks.

The narrative of sustainable urban development is undergoing its most significant transformation in a decade. For years, “Net-Zero” was the North Star—a mathematical equation where carbon emitted was balanced by carbon offset. However, as we settle into 2026, the limitations of this linear approach have become glaringly obvious. Offsetting does not solve resource scarcity. It does not recover the rare earth metals buried in landfills, nor does it insulate cities from volatile global supply chains.

We are witnessing the rise of the Regenerative City, powered by a suite of circular economy technologies that are no longer experimental pilots but essential infrastructure. This analysis explores how the convergence of AI, policy, and material science is rewriting the rules of construction and urban management.

The Digital Backbone: From Static Blueprints to Dynamic Material Banks

The most profound technological shift in 2026 is the maturity of the Digital Twin integrated with Material Passports. In the early 2020s, digital twins were primarily used for energy modeling. Today, they serve a far more radical purpose: they act as a real-time inventory of a city’s physical assets.

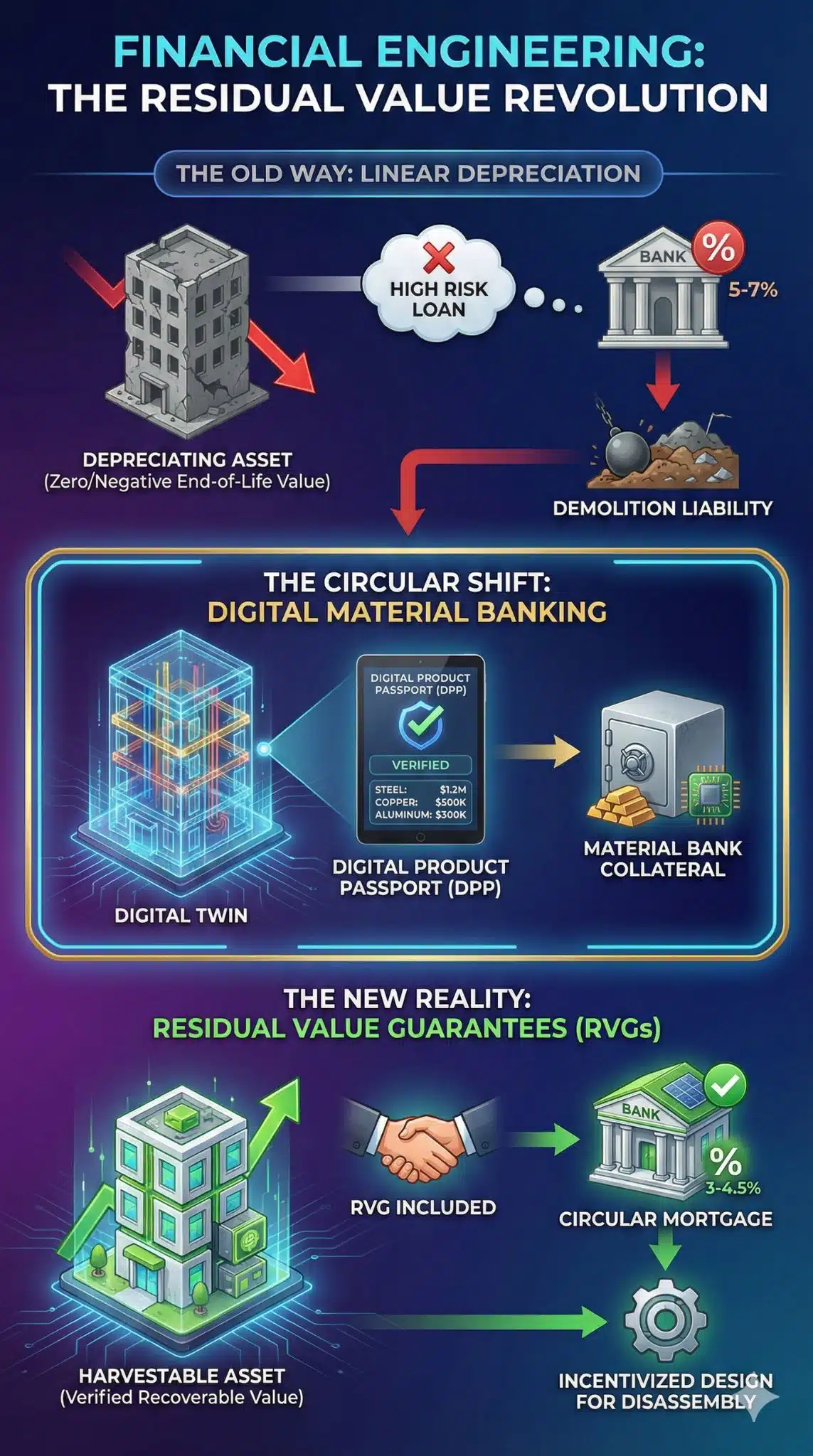

Platforms like Madaster have evolved from niche registries to central operating systems for smart cities. By assigning a “Digital Product Passport” (DPP) to every steel beam, copper wire, and concrete slab, cities are effectively turning their skyline into a “material bank.” This shift is crucial because it changes the financial valuation of a building. It is no longer a depreciating asset that eventually becomes a demolition cost; it is a repository of valuable commodities that can be harvested at the end of its lifecycle.

Key Technology Integrations 2026

| Technology | Function in 2026 | Impact on Urban Development |

| Dynamic Material Passports | Real-time tracking of material value, location, and condition. | Transforms buildings into financial assets based on material recovery value. |

| Generative Design AI | Algorithms that optimize for disassembly and reuse before construction begins. | Reduces construction waste by up to 40% by prioritizing modularity. |

| Blockchain Ledgers | Immutable records of material ownership and lifecycle history. | Eliminates “greenwashing” in supply chains and verifies circularity claims. |

This digitalization solves the “verification gap” that plagued earlier circular efforts. Investors can now see the residual value of materials in a building 30 years down the line, unlocking new financing models known as “Materials-as-a-Service” (MaaS).

Urban Mining: The New Geopolitical Imperative

While sustainability is the public face of the circular economy, the quiet driver is resource sovereignty. The geopolitical landscape of 2026 is defined by fierce competition for critical raw materials (CRMs) like copper, lithium, and cobalt—essential for the green transition.

Traditional mining cannot keep pace with demand. This has elevated Urban Mining from a waste management tactic to a strategic imperative. Cities are the world’s largest mines. The concentration of gold in high-end electronics waste is often 100 times higher than in natural ore.

Startups leveraging AI and computer vision, such as robotic sorting systems developed by companies like AMP, have reached a tipping point in efficiency. These systems can now identify and separate alloys with 99% accuracy, making recycled materials cost-competitive with virgin ores for the first time. In 2026, we are seeing the first “Refineries of the Future”—urban facilities that use bioleaching (using microbes to extract metals) to process e-waste within city limits, slashing logistics costs and carbon footprints.

Policy as Catalyst: The EU Circular Economy Act 2026

The adoption of the EU Circular Economy Act this year has acted as a massive forcing function. Unlike previous voluntary guidelines, this legislation creates a true Single Market for secondary raw materials.

Crucially, it harmonizes “End-of-Waste” criteria. Previously, crushed concrete might be considered “waste” in one country and “aggregate” in another, freezing cross-border trade. The new standardized rules mean that secondary materials can flow as freely as virgin ones. For the construction sector, this is a game-changer. It mandates that a percentage of all new public infrastructure must be built with secondary materials, artificially creating a robust demand shock that is driving investment into recycling tech.

Comparative Analysis: The Linear vs. Circular Regulatory Era

| Feature | The “Net-Zero” Era (2020–2025) | The “Circular Era” (2026–Post) |

| Primary Goal | Reduce operational emissions (Energy efficiency). | Reduce embodied carbon & resource depletion. |

| Waste Policy | Landfill taxes and diversion targets. | Mandatory “Right to Repair” & Ban on destruction of unsold goods. |

| Data Requirement | Energy Performance Certificates (EPC). | Digital Product Passports (DPP) & Material Circularity Indicator. |

| Economic Model | Take-Make-Waste (Linear). | Take-Make-Recover-Regenerate (Loop). |

Economic Implications: Winners and Losers

The transition to circular urbanism is creating a distinct divergence in the market. The “Winners” are companies that have successfully pivoted to service-based models. In the lighting industry, for example, companies are no longer selling lightbulbs; they are selling “lumens” via leasing contracts. They retain ownership of the physical fixture, incentivizing them to make products that are durable, modular, and easy to repair.

Conversely, the “Losers” are legacy manufacturers stuck in planned obsolescence models. As the cost of virgin materials rises due to scarcity and carbon pricing (CBAM), their margins are evaporating. The construction firms failing to adopt modular, off-site manufacturing techniques are finding themselves priced out of tenders that now heavily weight “circularity potential.”

Additional Analysis: The Retrofit Challenge & Financial Rewiring

While the “Regenerative City” vision often highlights gleaming new developments, the true battleground for the circular economy in 2026 lies in the existing building stock. Approximately 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 have already been built. The greatest challenge—and opportunity—is not in constructing new “material banks,” but in mining the “brownfield” sites of the 20th century.

The “Retrofit” Conundrum: Mining the Past

The shift from demolition to adaptive reuse has become the defining architectural challenge of the mid-2020s. In the past, demolishing a 1970s office block was a standard depreciation write-off. Today, under strict Scope 3 emission reporting requirements, demolition is a liability.

We are seeing the rise of “Surgical Deconstruction”—a process where AI-driven robots scan existing structures to identify salvageable components before renovation. Companies like Robo-Demolition are using hyper-spectral imaging to distinguish between asbestos-laden materials (which must be contained) and clean copper or steel (which can be monetized).

- The Analysis: This changes the economics of renovation. The “cost of removal” is now partially offset by the “revenue of recovery.” Real estate developers are no longer just land owners; they are becoming commodity traders, selling scraped steel and glass back into the supply chain to offset renovation costs.

Financial Engineering: The “Residual Value” Revolution

The financial sector has finally caught up to the engineering reality. In 2026, we are seeing the mainstreaming of “Residual Value Guarantees” (RVGs) in construction loans.

Previously, a bank viewed a building’s physical shell as having zero value at the end of its life (or negative value due to demolition costs). Now, with Digital Product Passports proving the existence and condition of high-value recyclable materials, banks are counting those materials as collateral.

Key Insight: If a building contains $2 million worth of recoverable steel and aluminum, the risk profile of the loan decreases. This is leading to “Circular Mortgages” with interest rates 25-50 basis points lower than traditional loans, specifically incentivizing developers to design for disassembly.

The “Product-as-a-Service” (PaaS) Tipping Point

The circular transition is also reshaping the tenant experience through the Product-as-a-Service model. In high-end commercial real estate, developers are stopping the purchase of elevators, HVAC systems, and even facades. Instead, they are signing 20-year performance contracts with manufacturers like Otis or Mitsubishi.

- Why this matters: When a manufacturer retains ownership of an elevator, their incentive flips. They no longer want to sell spare parts (which requires breakage); they want the machine to never break. This aligns the manufacturer’s profit motive with resource efficiency and longevity.

- The Result: We are seeing a crash in “planned obsolescence.” Equipment installed in 2026 is designed to be modular and upgradeable, rather than disposable, fundamentally altering the maintenance economy of cities.

The Geopolitical “Leapfrog” Effect

Finally, an overlooked trend is the “leapfrog” potential in the Global South. While Western nations struggle to retrofit aging infrastructure, rapidly urbanizing regions in Southeast Asia and Africa are adopting circular principles out of necessity rather than regulation. With imported raw materials becoming prohibitively expensive due to supply chain fragmentation, cities like Lagos and Jakarta are formalizing their informal waste sectors. They are integrating “scavenger” networks into official municipal waste management systems using mobile apps, creating a low-tech but highly efficient version of the “Urban Mine” that often outperforms the automated systems of the West in terms of pure recovery rates.

Summary of Extended Trends

| Trend | The “Old” Way (2020s) | The “New” Way (2026+) |

| Renovation | Demolish and rebuild. | Surgical deconstruction & adaptive reuse. |

| Financing | Building value based on rent rolls only. | Value includes “Material Bank” assets (collateral). |

| Equipment | Buy, maintain, discard. | Product-as-a-Service (Leasing performance). |

| Global South | Informal, unregulated waste picking. | App-based integration of informal recycling sectors. |

Future Outlook: The Rise of the “Regenerative City”

Looking ahead to 2030, the concept of the “Smart City” will be fully replaced by the Regenerative City.

We can expect:

- Bio-Integrated Infrastructure: Facades that cultivate algae for biofuel or absorb smog will become standard code requirements in dense metropolises.

- Hyper-Local Manufacturing: 3D printing with recycled urban plastic will allow cities to print furniture, spare parts, and even temporary shelters on demand, reducing reliance on global shipping.

- The End of Demolition: “Deconstruction” will replace demolition. Robotic disassembly crews will take buildings apart bolt-by-bolt to preserve component value, a process already being piloted in forward-thinking cities like Amsterdam and Singapore.

The circular economy is no longer just an environmental rescue mission; it is the only viable economic strategy for a resource-constrained world.

Final Words

The transition from Net-Zero to Circularity is no longer optional—it is the definitive economic moat of the late 2020s. As critical minerals become the new oil, cities that master “urban mining” and digital material banking will secure their sovereignty. The 2026 policy landscape is clear: waste is a design flaw, and regeneration is the new baseline for profitability. The future belongs to those who view their skyline not as static concrete, but as a dynamic, harvestable asset.