Every nation has a few figures who rise above their time and leave behind legacies that continue to shape generations. For Bangladesh, one of those figures is Zahir Raihan—a man who was not just a filmmaker but also a voice of resistance, a storyteller of truth, and a revolutionary who blended art with activism.

In only 37 short years, he created films, novels, and documentaries that still define our cultural and political imagination. Works like Jibon Theke Neya and Stop Genocide were not just artistic milestones—they were weapons in the battle for freedom, dignity, and justice.

Yet today, on his 90th birth anniversary, one question comes back to me with urgency: Can Bangladesh ever create another Zahir Raihan? It is not a simple question about cinema or literature—it is about whether our society, our industry, and our people can nurture another voice as fearless, as visionary, and as uncompromising as his.

As someone who grew up admiring his work and often wondered what he would create if he were alive today, I believe the answer is both hopeful and troubling.

The Making of a Legend

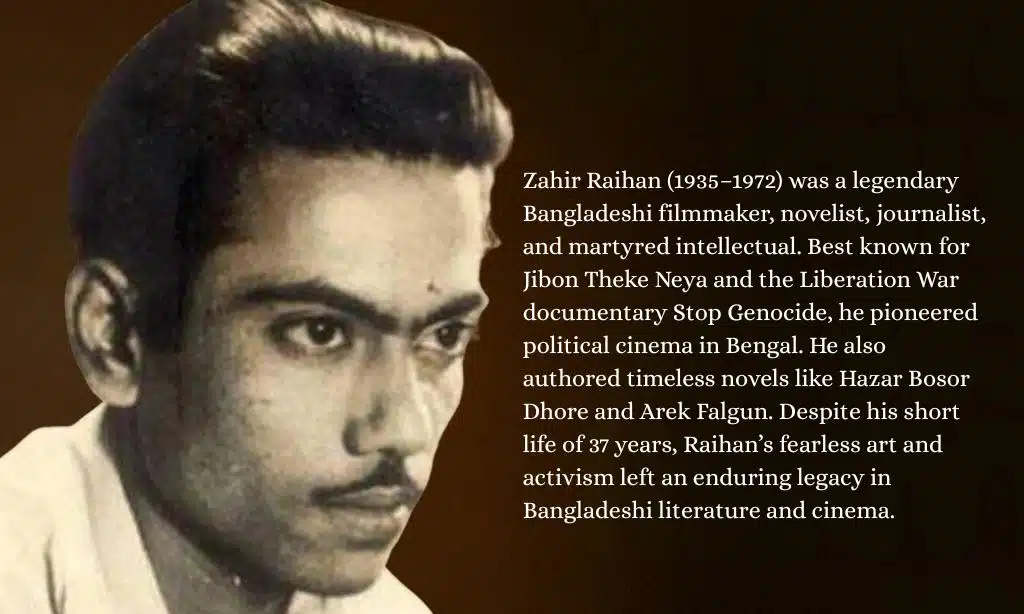

To ask whether another Raihan can emerge, we must first remember how the first one was made. Born in 1935 in a small village of Feni, Raihan stepped into a world of turbulence—colonialism, partition, and later the growing struggle for Bengali identity. His life was tied with politics from the beginning.

He was among the first group to break Section 144 during the Language Movement of 1952, risking jail for the right to speak in Bengali. That boldness—mixing personal sacrifice with collective struggle—was always part of his DNA.

Raihan was not limited to one form of creativity. He was a journalist, novelist, short story writer, and filmmaker. His early short story collection Suryagrahan and later novels like Hazar Bosor Dhore and Arek Falgun revealed his deep sensitivity to society’s pain. But cinema became his greatest tool. Entering the film world in 1957, he quickly rose from an assistant to a director who reshaped the language of South Asian cinema.

He was not chasing glamour. He was chasing truth. When he made Jibon Theke Neya in 1970, he turned the political oppression of the Language Movement into a metaphorical family drama. Audiences understood instantly—it was their story, their anger, their resistance. During the Liberation War, instead of staying safe, he went to India and made Stop Genocide, a documentary that exposed the brutality of the Pakistani army to the world. Satyajit Ray himself praised it, calling it one of the most powerful films ever made about human suffering.

Raihan was, in every way, a revolutionary storyteller.

Why Zahir Raihan Was Irreplaceable

Some might argue that every generation produces great artists. But Raihan was not just a great artist—he was a cultural force shaped by history itself. His timing was extraordinary. Bangladesh was on the edge of birth, and he became both a witness and a participant in that process. He had the courage to merge politics with art when both could cost him his life.

His uniqueness came from the way he wore many hats with ease. He could write novels about love and loneliness, yet also make films that questioned authoritarian power. He could report as a journalist in the morning and edit a documentary for the liberation struggle by night. Few people can carry such creative energy across so many forms.

And then there was his age. He achieved all this before he turned 37. Most filmmakers spend their first decades only learning their craft. Raihan had already left behind a body of work that defined an entire nation’s culture. His sudden disappearance while searching for his brother Shahidullah Kaiser in January 1972 turned him into a legend. The tragedy of his absence makes us feel even more how irreplaceable he was.

Personally, when I revisit Jibon Theke Neya or reread his novels, I am struck by how alive his voice feels even today. It is as though he still speaks to us, reminding us that art should never be afraid of truth.

The Bangladesh of Today vs. Zahir Raihan’s Time

To wonder if another Raihan can emerge, we must compare his Bangladesh to ours. The 1960s and early 70s were a period of political urgency. Every day was about survival, identity, and justice. In that climate, art was naturally political. Filmmakers, writers, and intellectuals were not just entertainers—they were freedom fighters in their own way.

Today, Bangladesh is very different. We live in a globalized, digital, consumer-driven society. Political struggles exist, yes, but they often get drowned in entertainment, commercial priorities, or online distractions. Cinema is dominated by formula plots, star-driven spectacles, and business concerns. OTT platforms are growing, but they often focus on what sells, not what challenges.

Censorship, too, is still a reality—sometimes subtle, sometimes strong. A film like Jibon Theke Neya, which openly criticized authoritarianism, would face enormous hurdles today. Would it even get approval for release? Would audiences, used to fast-paced thrillers and light comedies, embrace such a politically charged metaphorical drama?

This is where the challenge lies. Raihan’s Bangladesh needed him—and welcomed him. Today’s Bangladesh may need another Raihan, but is it willing to support one?

Is There Space for Another Raihan in Modern Cinema?

Let us look at our current film industry. There are talented directors—Mostofa Sarwar Farooki, Giasuddin Selim, and Tareque Masud before his tragic death. They have pushed boundaries, experimented with new narratives, and even taken Bangladeshi films to international festivals. Yet even they admit to struggling against funding issues, censorship boards, and an audience trained to prefer safe entertainment.

Could a new Raihan rise here? Possibly, but it would be much harder. Raihan was allowed to work in a time when cinema was respected as a vehicle of national identity. Today, cinema often competes with TikTok and YouTube shorts. The value of long, reflective, metaphorical films has decreased.

But there is hope. OTT platforms like Netflix and Hoichoi are expanding access. Independent filmmakers are crowdfunding projects. If a new Raihan emerges, perhaps his or her platform will not be the cinema hall but the global digital screen.

Beyond Cinema—Where Might a “New Raihan” Emerge?

Perhaps we are looking for Raihan in the wrong place. The next Raihan may not be a filmmaker at all. He or she could be a digital activist who uses short documentaries on YouTube to speak truth to power. Or a VR storyteller who recreates historical events so the youth can experience them emotionally. Or even an AI-powered documentarian who uses technology to reveal hidden truths.

The spirit of Raihan is not limited to celluloid. His essence was courage, vision, and truth-telling. If those values can be carried into new mediums, then yes, we may indeed have “another Raihan,” though not in the traditional sense.

I often wonder—if Raihan lived in 2025, what would he do? I imagine him with a camera, yes, but also with a laptop, editing a documentary on Gaza, climate refugees, or the digital exploitation of workers. He would still be a voice for the voiceless, just using different tools.

Why We Still Need Another Zahir Raihan

The painful truth is that Bangladesh still faces many struggles—inequality, corruption, censorship, cultural conflicts, and global challenges like climate change. Art that entertains is important, but art that challenges is essential.

That is why we still need another Raihan. His courage to turn art into protest is something we desperately lack today. A Raihan-like figure could remind us that films, novels, and documentaries are not just for fun but for awakening.

When I think of him, I see not only a filmmaker but also the conscience of a nation. And every nation needs a conscience, especially one that speaks through the universal language of art.

Final Words

So, can Bangladesh ever create another Zahir Raihan? My honest answer is: not in the same way. The man himself was unique, a product of a historical moment that cannot be repeated. But the spirit of Raihan—the fearless merging of art and activism—can be reborn in new forms.

If we nurture creativity, allow freedom of thought, and give space to brave voices, then yes, another Raihan can emerge. If we silence dissent, prioritize money over meaning, and fear truth, then no.

Zahir Raihan may not return, but his absence is also a call. It reminds us that the work he left unfinished must be carried on by others. The question is not just whether Bangladesh can create another Raihan, but whether we are willing to become a little bit like him ourselves—fearless, visionary, and uncompromising.

On his 90th birth anniversary, I close my eyes and imagine him smiling. Perhaps he would be pleased to see us still debating, still questioning, still searching for voices like his. Perhaps that is his greatest legacy: that even in his absence, Zahir Raihan makes us ask the hardest questions about art, truth, and courage.