As first-person (FPV) drone racing becomes more popular, AI implementations have improved their performance versus human pilots. While there is still much unexplored land in this field of research, it has the potential to impact a variety of real-world applications for autonomous drones.

Researchers from the University of Zurich revealed an autonomous drone control system capable of outflying human pilots on race circuits in 2021. They’ve created a successor in the two years since, claiming to have defeated three world-champion FPV drone racers.

The new sport requires contestants to fly a small drone through a series of gates as rapidly as possible, with the video feed from the drone’s camera attached to the pilot’s goggles. Racers’ quick reflexes and high level of expertise test the boundaries of drone mobility, making them an appealing subject for research into autonomous control systems.

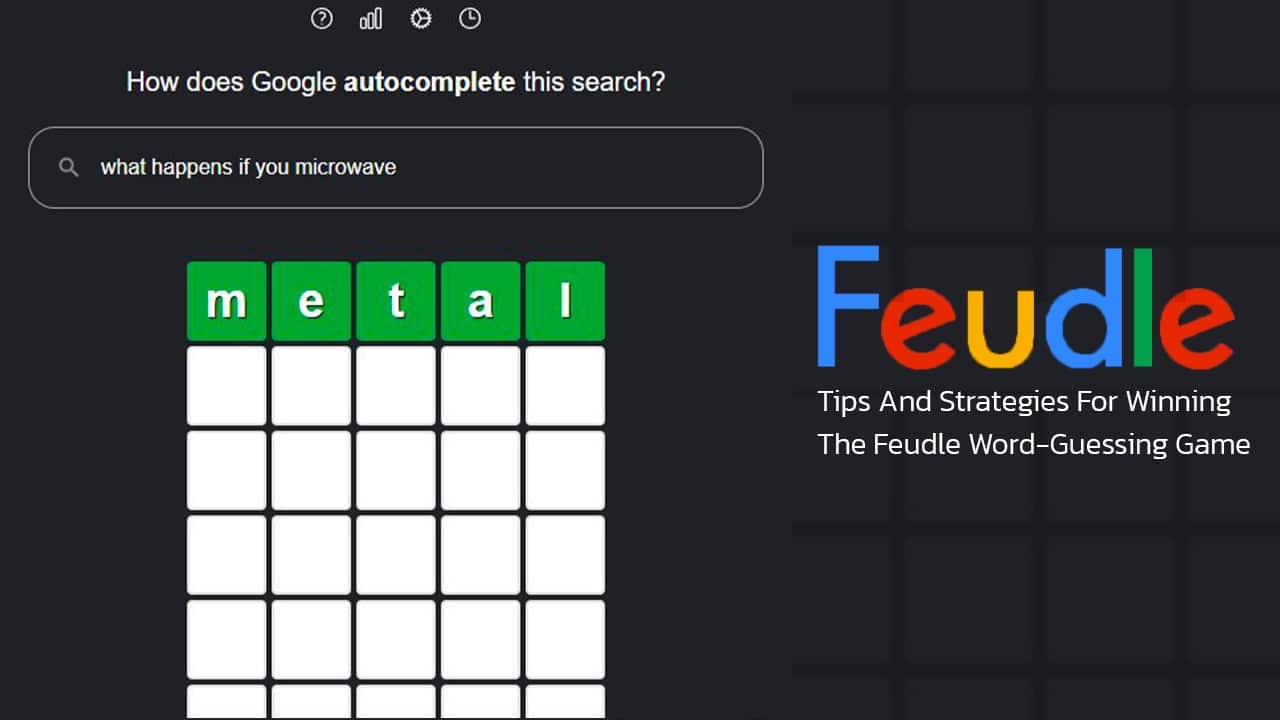

Swift’s AI was trained using a neural network and data from an onboard computer, a camera, and an inertial sensor. Swift set track records during the test, defeating three international world champions, owing to its ability to take much tighter corners than the human pilots. Autonomous racing system research is almost as ancient as drone racing, but recent achievements from the University of Zurich have taken it to a new level.

The most noticeable difference is that, although the human racers spent a week training on the test course, the artificial intelligence (AI) training procedure took only about an hour on a regular workstation desktop. The drone may have two advantages over the racers’ brains: it analyzes information faster and perceives inertia in a manner that humans do not. Swift’s video stream, on the other hand, was only 30Hz, whereas the pilots’ cameras refreshed at 120Hz, providing them much more visual data.

Swift has only been tested on one indoor circuit, whereas drone races are done in a variety of indoor and outdoor venues. It’s unknown how self-driving systems like Swift would handle things like wind or changing lighting conditions, so there’s definitely potential for additional research.

The findings of these and other tests could have far-reaching effects beyond drone racing. They could aid in the improvement of how self-flying drones navigate real-world settings for applications such as deliveries, search and rescue, combat, and others.