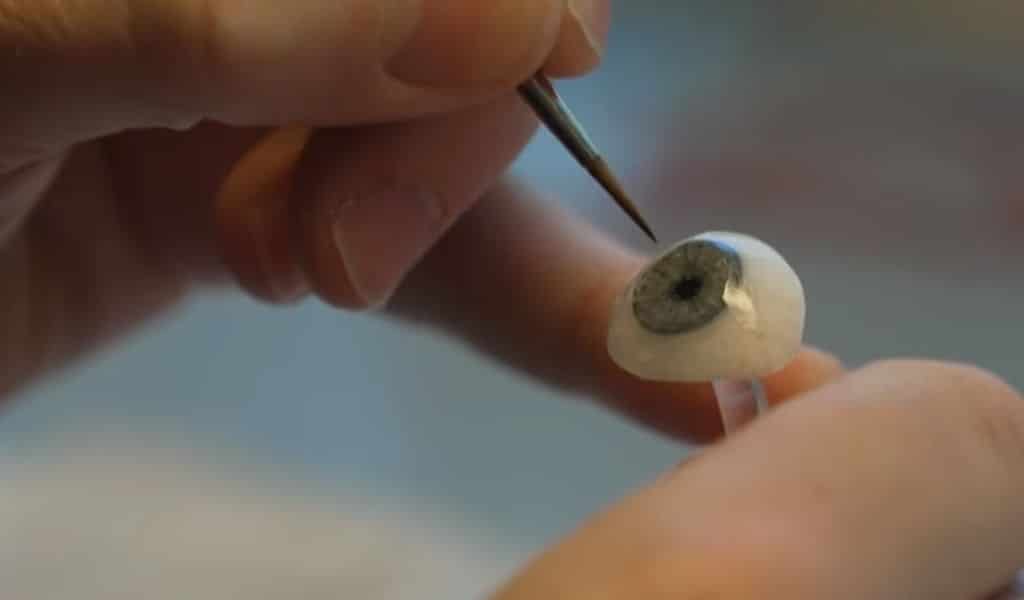

Nicholas Puls makes tiny works of art in the workshop of the hospital where he works. Each brushstroke and dot of color is carefully added.

The soft-spoken ocularist makes fake eyes for people who have had cancer, serious accidents, or were born with only one eye or none at all.

Mr. Puls said, “Everything is unique, so no two patients are the same.”

It takes a lot of time and needs modeling and painting skills that most people don’t have.

Mr. Puls said, “It can be a stressful job because you can spend a long time making an eye and then look at it and think, “No, I’m not happy with that.”

About 10 people a year go to the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (RBWH) because they need a full orbital prosthesis. This is a silicone eye socket that holds a mechanical eye.

About 100 people a year need an ocular prosthesis, which is an artificial eye that goes into the person’s natural eye socket.

“My role is important, and I don’t take it lightly,” said Mr. Puls.

“It’s very important to the patients because it gives them back their confidence.”

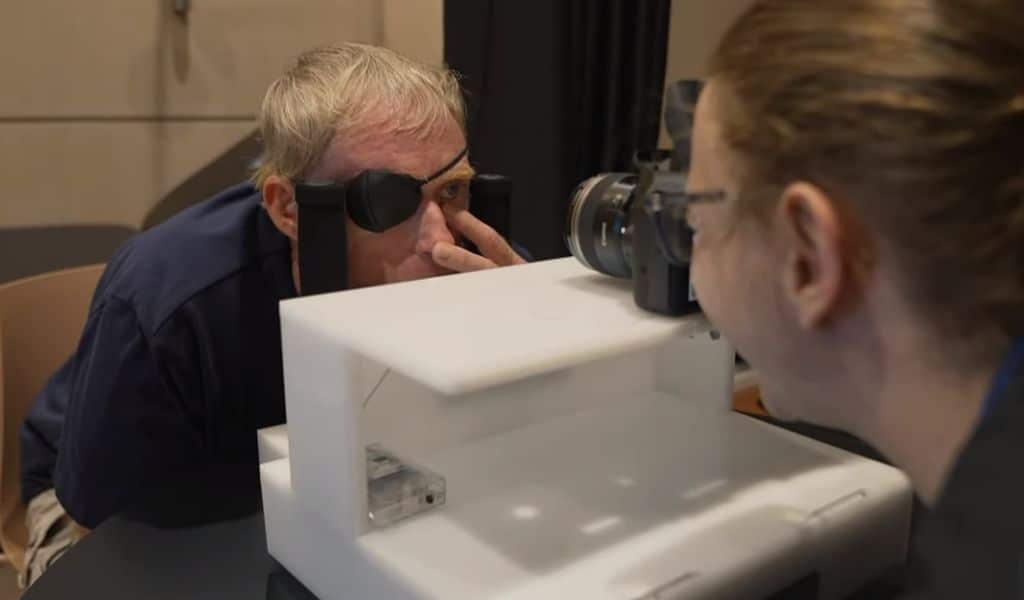

Craig Faull from Sunshine Coast is one of these people.

He was told about 15 years ago that he had skin cancer on his right eyeball. His doctor said it was like an iceberg.

Mr. Faull said, “It was just a little tip at the top, and the roots just kept going down. He’d never gone as deep before [to remove the cancer].”

When the cancer returned five years later, he had a 12-hour procedure.

They removed my eye and bone, and mesh was reinserted, along with skin grafts, claimed Mr. Faull.

The plumber has now been cancer-free for ten years, and although he admitted that depth perception sometimes be difficult, he has adjusted well.

“In a way, I was lucky. Mr. Faull said, “I didn’t lose my eye all at once because my eyelid slowly closed.”

“I’d sort of gotten used to having one eye.”

But there have been effects on people’s lives and feelings.

“That’s probably the hardest part,” Mr. Faull said, referring to how people reacted, such as by looking or talking.

He has a hand-made orbital replacement that he only wears to parties so that it doesn’t get broken.

Mr. Faull said, “You feel normal, like no one is looking at you, staring at you, or judging you.”

He can’t say enough good things about the people who made his replacement.

“Those people are real, real artists.”

The Machine that can Print New Eyes

But technology is bringing about change, as it has in so many other fields.

The cutting-edge Herston Biofabrication Institute is just a short walk from Nicholas Puls’s shop.

When it opens in 2020, the institute will be the first of its kind in Australia. It will focus on 3D scanning, modeling, and printing of medical devices, as well as study into how biocompatible materials could be used in the future for implants.

A group of scientists, led by senior research fellow James Novak, are testing 10 patients to see how 3D printed eyes look and feel compared to eyes that are made by hand.

“We have this amazing technology that can 3D print full-color eyes. We think it’s amazing, but what do the patients think?” Dr Novak said.

The team makes the fake eyes with 3D scanning and high-resolution photos.

Dr. Novak said, “By digitizing part of this process, we can take a picture of the patient’s existing eye, mirror it to the other side, and make an exact copy of that.”

“In the past, that had to be done by hand, and there was obviously room for error. The skill of the ocularist also played a big role in how accurate the eye was.”

The technology could make things more reliable and also saves time.

Dr. Novak said, “Once we’ve digitized and made the patient’s first eye, we can 3D print them as often as we need to and send them to the patient if they’ve lost the eye, hurt it, or just need back-ups.”

“It’s something we can do quickly, cheaply, and that will make a huge difference even though it’s a small thing.”

If the patients are happy with the printed versions, the next step would be a bigger trial of both orbital and eye prostheses.

A clinical trial will allow us to assess the materials’ compatibility and long-term safety on a much larger population of patients, according to Dr. Novak.

The RBWH Foundation has been wonderful in sponsoring this tiny study, but in order to conduct a much larger cohort study, getting some cash would allow us to do that on a wider scale.

So, is the Machine Poised to Replace the Human?

Dr. Novak and Mr. Puls disagree.

Dr. Novak added, “I don’t think we’ll replace that very rapidly with digital technology. Once we 3D print the eyeballs, they still need to be fine-tuned to properly fit into the eye socket.

The optimum method, in our opinion, is a hybrid one that combines components of what a human can do well with those that a 3D printer can do well.